Why should a PM speak French? Political reality.

Stephen Harper once railed against bilingualism, but came to understand that not knowing French was a sure way to lose

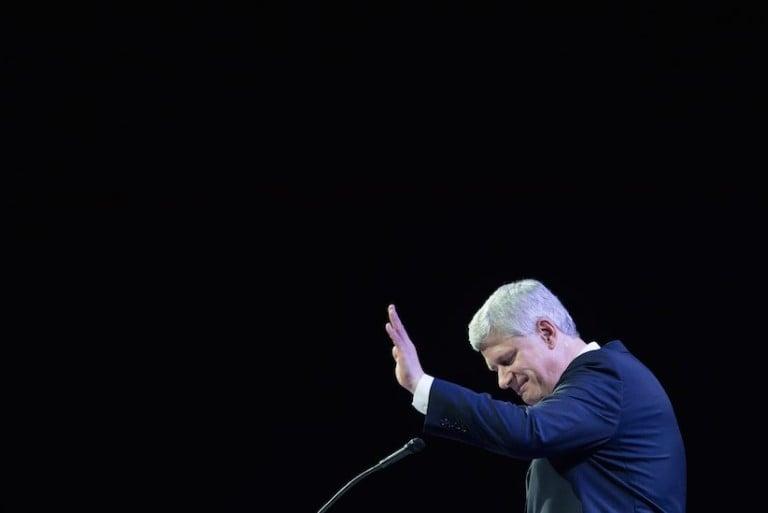

Former prime minister Stephen Harper waves as he steps away from the podium after addressing delegates during the 2016 Conservative Party Convention in Vancouver, B.C. on Thursday May 26, 2016. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

Share

Before the advent of Stephen Harper, a remarkably successful conservative politician, there existed a fellow named Stephen Harper, plucky young conservative egghead. It was this Harper who, in 2001, wrote an oft-quoted column about official bilingualism. “As a religion, bilingualism is the god that failed. It has led to no fairness, produces no unity and cost Canadian taxpayers untold millions,” wrote Harper in the Calgary Sun.

It was in egghead Harper that we best saw the Harper id: brash, mouthy and given to public temper tantrums in print and elsewhere. And here it was in full display. Bilingualism—“a dogma which one is supposed to accept without question”—was at best an expensive folly and at worst a lie perpetrated by Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals. “Canada is not a bilingual country,” Harper wrote, noting how his own early bilingual education had done nothing to Frenchify his stubbornly English tongue.

Given the vitriol egghead Harper heaped on official bilingualism, you’d think politician Harper would have wasted no time in turfing the policy. Yet it was a far different Harper who became prime minister five short years after he committed those words to print. This Harper was fluently bilingual, began all his speeches in French and, as prime minister, would oversee one of the biggest funding boosts to federal bilingual programs in over 40 years. “As Canadians, we are very proud of the coexistence of our two national languages,” Harper wrote in 2013.

The reason behind Harper’s quick change is simple enough. Harper the politician realized what Harper the egghead didn’t: French is necessary if you want to lead the country.

Which brings me to the recent column by my colleague Peter Shawn Taylor. In it, Taylor bemoans the return of the “eternal Canadian handwringing over our leaders’ language skill.” He notes people like potential Conservative leadership candidate Kevin O’Leary shouldn’t be disqualified simply because they don’t speak French. “It’s time to erase this unwritten rule that no one can be considered a credible candidate for prime minister unless they speak both official languages,” Taylor writes.

There is no such unwritten rule that a leadership candidate speak both official languages; rather, the ability to speak English and French is a political reality, which is a far more compelling reason for any would-be politician in this country.

First, a little math. Quebec has about 6.5 million francophones, or just under 80 per cent of that province’s population, spread out over 78 federal ridings. Outside Montreal, most of those ridings are overwhelmingly French. Suffice to say that any aspiring politician venturing into, say, the federal riding of Quebec City (92 per cent francophone) would be laughed back onto the Trans-Canada Highway were he or she not able to at least stump in French. Translation: not knowing French is a fantastic way to hobble yourself in the race for nearly 25 per cent of the country’s federal Parliamentary seats.

This is all the more true for the next Conservative party leader. An astute politician, Harper realized that beyond the pinko reprieve of Montreal, much of Quebec is small-c conservative in its outlook, if not its political leanings. Yet harvesting this sentiment for political gain would have been impossible had Harper stuck to his stubborn eggheadish beliefs of yore.

And what of the notion that unilingual anglophones are loath to vote for someone who is bilingual, marginalized as they are under this system? A 2016 Neilsen poll suggested that 86 per cent of Canadians actually believe the prime minister should be bilingual. Apparently we’re an aspirational bunch. We aren’t all bilingual, far from it, but we believe our prime minister should be.

This is exactly why most of the 13 declared candidates in the race for Conservative Party of Canada leadership gamely took to a Moncton stage recently and proceeded to butcher la langue de Molière with such earnestness that it might have been a Heritage Minute. Like poutine and pond hockey, leaders speaking French poorly has become an enduring Canadian cliché. As Harper demonstrated, getting better at it has become part of the job.

Political reality, not an unwritten rule, will ensure that the winner of this particular race will spend a significant amount of time on the French language’s admittedly steep learning curve. Their French doesn’t have be anywhere close to being perfect. The person need only speak well enough to be understood, and bad enough to be pitied. But learn it they will. The proof lies in history, not its laws.