How athletic programs’ drive for success creates the conditions for abuse

Opinion: The rot in USA Gymnastics is ingrained in its roots and culture—and that should be a lesson for demanding programs in other sports

Mattie Larson of the U.S. performs on the uneven bars during the women’s qualifying session for the World Gymnastics Championships in Rotterdam, Netherlands, Sunday Oct. 17, 2010. (AP Photo/Bas Czerwinski)

Share

Beyond inherent ability and genetic advantage, success in high-performance artistic sport—gymnastics, ballet, figure skating—requires militant self-discipline and unwavering dedication to training. All talent begins raw, and each sport has its own developmental program where young athletes hone specific skills and build key areas of strength which underlie the advanced demands of the competitive system. While elite programs differ in terms of sport-specific training strategies, the best and worst systems share a common, underlying component: abuse, either in their zero tolerance for it, or the centrality of it.

My own time as a dancer and gymnast saw the full range of abuses, and escaping one kind of mistreatment only led to being the target of and witness to another. For me, the most destructive was being subjected, starting at the age of 8, to an abusive sort of body-policing where my young physique was relentlessly scrutinized and compared to the bodies of girls who were older—girls whose athletic and physical development were naturally more advanced than my own.

I was told, repeatedly, how horrible my body was, where it looked wrong, how unacceptable it might forever be. I was told I was too fat to have friends; my weight and measurements were strictly monitored and widely broadcast. All talent was rendered insignificant by my apparently horrendous self. I was shamed, belittled and humiliated, over and over, and I developed a severe eating disorder by age 11, relapsing once at 14. The anorexia was ultimately surmountable. The intense self-hate and outright abhorrence of my body, however, was not.

Though my own work ethic and drive to train ultimately earned that lean, muscular body, enviable strength and elite level of fitness as an older athlete, my grim self-assessment was firmly, irrecoverably ingrained—which affects me to this day.

That’s why the excruciating testimony in the sentencing of disgraced sports doctor Larry Nassar resonated so deeply for me, and I suspect for other female athletes who’ve been through the same. In addition to the horrors of Nassar’s serial molestation, the stories of endemic abuse by coaches and staff forced USA Gymnastics (USAG) to acknowledge the truth of its system, and the rot at its core—a rot that too often exists in programs across competitive athletics.

Last week, USAG complied with the U.S. Olympic Committee’s ultimatum for mass resignations from the director’s board, preventing the USOC from decertifying USAG, which would have stripped its status as the sport’s governing body. Regardless of the intentions behind this purge, the lifeblood of USAG’s twin cancers remain.

The first: An ideology where coach deification and institutional worship results in unquestioned, untouchable authority—the ideal conditions for abuse to thrive. When not enduring mistreatment, athletes are forced to be complicit in cruelty toward others. Speaking up will incur further abuse or outright end a career. Less powerful coaches, too, find they can do little more than witness in silence. Either their concerns will be ignored, or they’ll be out of a job. Sometimes, it’s both.

The second: A method of training built on insidious forms of abuse, where harm to the mental and emotional well-being of young female athletes is but collateral damage in the quest for glory, and where the aftermath—eating disorders, depression, anxiety, self-harm, suicide—is shrugged off as somebody else’s problem.

We saw how entrenched this was in the survivor testimony at the Nassar trial. On the sixth day, former U.S. national team member and 2010 floor champion Mattie Larson named two now-retired figures central to the notoriously abusive system that currently exists: Bela and Martha Karolyi, icons in their field, whose Ranch served as the national team’s training centre, hosting camps billed as integral to Olympic glory.

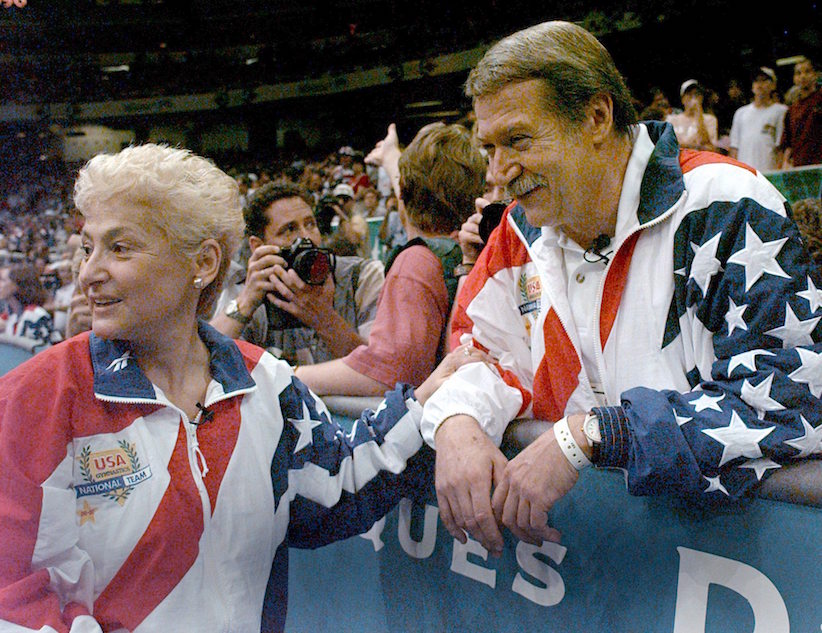

Before defecting to the U.S. in the ‘80s, the Karolyis were the power couple of Romanian gymnastics. At the 1976 Montreal Olympics, their gymnast Nadia Comăneci scored the sport’s first perfect 10 at an Olympic Games. In America, their stars included gymnastic legends Mary Lou Retton and Kim Zmeskal, as well as two members of the 1996 Olympics’ “Magnificent Seven,” Dominique Moceanu and Kerri Strugg. In a glowing 2016 profile in the New York Times, Martha credited her system, and the ranch, as the prime reason that the “United States dominates the world of gymnastics.”

Larson, however, testified the Ranch was little more than a USAG-sanctioned centre for uninterrupted physical, emotional, psychological—and, from Nassar, sexual—abuse.

She told of an “intense and destructive six-year eating disorder” that developed in an effort to be skinny enough for the coaches’ affection and approval; the Karolyis were notorious for imposing a severe caloric restriction on athletes on top of the schedule, which demanded overtraining. During one camp, Larson was told she was fine by the doctor Nassar, despite later revelations that she had dislocated and fractured both ankles. She also recounted a time she intentionally injured herself in a desperate bid to escape the relentless abuse at the Ranch.

“While [Nassar] is a mentally deranged pedophile, he is not the head of the monster,” wrote Valorie Kondos-Field—head coach of the six-time champion UCLA women’s gymnastics team—in a post published days before Larson’s testimony. That, she said, was the cult of Karolyi: “Martha, and before her Bela, and before him Don Peters, who has been banned from coaching for his own sexual abuse allegations. For decades they established a culture of abuse that was widely accepted and mimicked by other club coaches because ‘we won medals.’ ”

This draconian method of “creating champions” is what allowed Nassar to prey with maximum reward, especially at the Ranch. He befriended the athletes, offered an empathetic, kind respite from the ongoing viciousness, and masterfully groomed each young gymnast for use to satisfy his own depraved sexual pleasure. While Nassar has been made to face consequences, and despite USAG’s vow to implement policies to better protect athletes from sexual misconduct, there has been no commitment to end the methodical mistreatment which remains.

Having coached 46 former U.S. national team members through their NCAA gymnastic careers, Kondos-Field witnessed the fallout of the system where “verbal, emotional, and physical abuse were simply the way of life.” She identified Larson as the most “egregious case” she’d seen of a young woman so thoroughly destroyed by the elite stream.

Following three weeks of living as a persona non grata after being blamed for America’s failure to secure team gold at the 2010 World Championships, Larson called Kondos-Field to say she was quitting elite to come to UCLA. When Kondos-Field asked why she’d do that so close to the Olympics, Larson replied: “Because I’ve become invisible. I actually pinch myself at times to make sure I am still alive and not a ghost.”

“I never felt so small and disposable in my life,” Larson said of that experience in her courtroom testimony. And in naming another notable figure, she exposed how inescapable the abuse remains even without the Karolyis at the helm. “It truly bothers me that one of the adults who treated me this way…is the new national team coordinator, Valeri Liukin. I hope for the sake of the current and future national team members he has changed.”

Liukin is gymnastics royalty—a top-tier figure, a two-time Olympic champion, and “one of the most highly regarded coaches in all of gymnastics,” boasts the USAG. Liukin is also the father of beloved American gymnast Nastia, whose awards include the coveted all-around Olympic title from the 2008 Beijing Games.

This wan’t the first time Liukin has been cited as abusive—two-time All-American and Junior National champion Katelyn Ohashi has spoken of aggressive body shaming and weight policing despite her being 70 pounds at the time, leading to bulimia—but it was certainly the most public, and thus inescapable, accusation. And when he replaced Martha as national team coordinator in September — four days after the Indianapolis Star first published Rachael Denhollander’s allegations against Nassar, and one month after its initial bombshell investigation into the systemic cover-up of sex abuse in the sport — the proud and firm believer in the Karolyi method planned for business as usual.

“There is no point in changing something that isn’t broken,” he said at the time. “… We’re winning a lot of medals, and that’s what we hope to continue to do.”

That system—in which Liukin has been involved since 1999, employing methods he endorses and outcomes he’s entirely pleased with—was the one with shattering repercussions heard in that Michigan courtroom. Nassar, too, was part of that system. And Liukin saw no reason for concern. None.

When USAG recently, belatedly, agreed to close the Karolyi Ranch, Liukin offered his own facility as an interim training centre. Though the athletes would be spared of having to train in the place they were abused by Nassar, they would continue to endure every other abuse of the program.

If USAG is sincerely dedicated to a complete overhaul—if the intention is to truly establish a zero-tolerance attitude regarding the mistreatment of athletes—they will move to replace Liukin with someone outside the Karolyi circle. They will work to find an esteemed coach who isn’t known for targeting athletes in a terribly personal, cruel manner.

USAG has the power to deliver the final blow to the Karolyis’ destructive legacy. Liukin’s future role within the organization will be telling of how much power the old guard maintains in the future, and will send a message to other sports authorities about the need for total reform in their own ranks. After all, as Larson concluded in her testimony: “There is another way, a healthy and supportive way, to make champions.” For gymnastics to have a future, the USAG must believe that a demanding, disciplined program which expects excellence does not need to be abusive. It needs Larson to be right. The good news is that she is.