No protection for asylum seekers at U.S.-Mexico border

Sara Gold and Andrea Salguero: There are some 15,000 asylum seekers waiting in Ciudad Juárez due to the U.S. government’s ‘Migrant Protection Protocols’

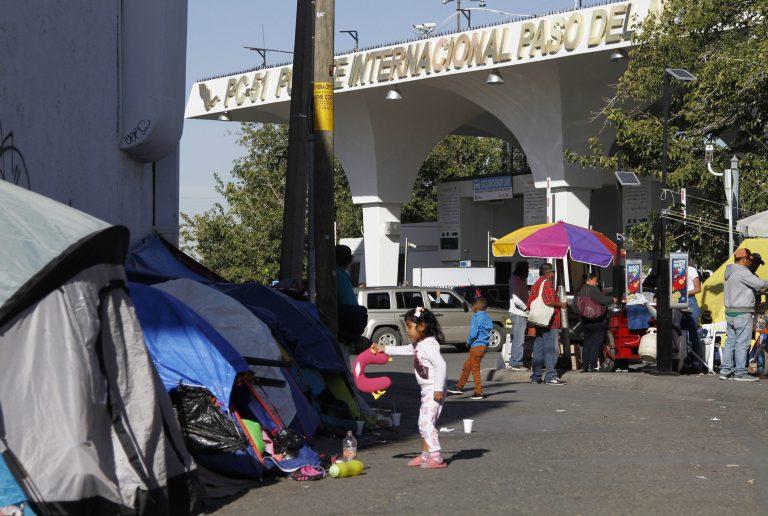

In this Thursday, Oct. 17, 2019 photo, a girl plays with a neck pillow in the street outside her family’s tent in Juarez, Mexico, near the border with El Paso, Texas. (AP Photo/Cedar Attanasio, File)

Share

Sara Gold is a law student at McGill University who works on issues related to Latin America and the law. Andrea Salguero is a law student at McGill University whose interests include immigration and labour law.

In October 2019, we spent a week volunteering with the Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center. Las Americas is a non-profit dedicated to serving the needs of immigrants in El Paso, Texas. One of the first cases we encountered was that of Mariana and Carlos (whose names have been changed to protect their identity). Mariana is battling Stage-4 terminal liver cancer, with her husband Carlos by her side. Her dying wish is to see her daughter, who is living in the U.S., before she passes away.

She and her husband were placed in the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), otherwise known as “remain in Mexico,” a policy that requires migrants to wait in Mexico until their court date. This process can take months, or sometimes even years. Having witnessed the impact of the program on the life of Mariana, Carlos, and countless others, we’ve seen that the policy threatens the livelihood and safety of asylum seekers stranded across the U.S.–Mexico border.

Migrants waiting for their court dates are living under dangerous conditions in overcrowded tents and shelters in Ciudad Juárez. We witnessed immigration court in El Paso, Texas, where migrants go to have their cases heard, and where proceedings are disorganized, chaotic and insensitive.

In January 2019, the U.S. government implemented the MPP program as a more “humanitarian” approach to manage the large numbers of migrants seeking asylum along the U.S.-Mexico border. MPP requires non-Mexican nationals—individuals from countries like Cuba, El Salvador, Venezuela, and others—entering the U.S. by land from Mexico, to wait in Mexico for the duration of their immigration proceedings. The program was intended to prevent human smuggling and to re-allocate resources to meritorious asylum claims.

However, MPP has had the exact opposite effect. At present, there are more than 60,000 migrants stranded in the most dangerous cities of the world along the U.S.-Mexico border. For scale, there are more people in MPP than there are people detained in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facilities on any given day in the entire United States—43,826 as of Dec. 9.

MPP exposes vulnerable migrants to danger and insecurity. When a migrant first arrives to the U.S.-Mexico border, they are given a unique identifier called an alien number and placed in MPP. Those without sufficient funds to secure long-term accommodation are forced to live in tent cities or overcrowded shelters. Conditions on the streets are dangerous for migrants, who are vulnerable to kidnapping, extortion and human trafficking. Employment opportunities are limited and access to adequate medical care and social services is almost non-existent. Those who stay in charity- or church-operated shelters report living in fear of regular raids and attacks.

Since the start of MPP, Human Rights First, a non-profit, non-partisan international human rights organization, reports there have been over 340 reported cases of rape, kidnapping, torture and other violent attacks against migrants. Many attacks go unreported. Additionally, migrants in MPP face additional hurdles when they attend immigration court in El Paso like lack of legal representation, logistical challenges and judicial indifference.

Less than two per cent of individuals placed in the MPP are represented in their immigration court proceedings. Most of the 15,000 individuals waiting in Ciudad Juárez are unrepresented because of the obstacles and liabilities American attorneys face to represent clients across an international border. Some may even be targeted for kidnapping and extortion when they visit clients in Ciudad Juárez. Not many lawyers are willing to take the personal risk. If a lawyer succeeds in removing someone from MPP to wait for their court date in the U.S., their chances of obtaining legal representation increases by a staggering 1,800 per cent. This underscores the importance of access to legal representation as well as the structural disadvantages migrants face while attempting to navigate the complexities of immigration law from another country.

The entire court process—including travel to and from the court—is taxing for migrants. On their court date, migrants are told to meet at the border at 4:30 a.m. and individuals are then bused into El Paso for an 8:30 a.m. hearing. The days are long and challenging for parents who must care for small children. At all times, migrants are heavily guarded by ICE officers.

When we attended court to support two clients of Las Americas, the judge was over two hours late, arriving to court with a cup of Starbucks coffee in hand. Even more shockingly, when the clients’ lawyer asked where the clients should wait in the weeks pending the judge’s decision, neither the U.S. government lawyer nor the judge knew the answer.

Even when migrants are assigned a judge to hear their asylum case, it is highly unlikely that they will be granted asylum in El Paso. In the last five years, less than seven per cent of asylum-seekers have been granted asylum in the region. Some individual judges in El Paso have denial rates ranging from 72 to 100 per cent.

These are the circumstances facing migrants such as Mariana and Carlos. The MPP program has closed the Southern border to migrants. It has been more effective in design and outcome than any physical wall. However, human resilience and perseverance remain. Las Americas, through herculean efforts, were able to help Mariana and Carlos cross the border, and advocate for her removal from the program. Sadly, their freedom to leave Mexico was only exceptionally granted because Mariana’s illness is life-threatening. Mariana will remain in the U.S. to peacefully pass away in the company of her daughter.