Maybe Canadians aren’t more enlightened about immigrants, after all

A survey finds that Canadians’ views on immigrants are close to those of Europeans and Americans. Could our political system be what sets us apart?

Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau shakes hands with a Syrian refugee during Canada Day celebrations on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, July 1, 2016. (Chris Wattie/REUTERS)

Share

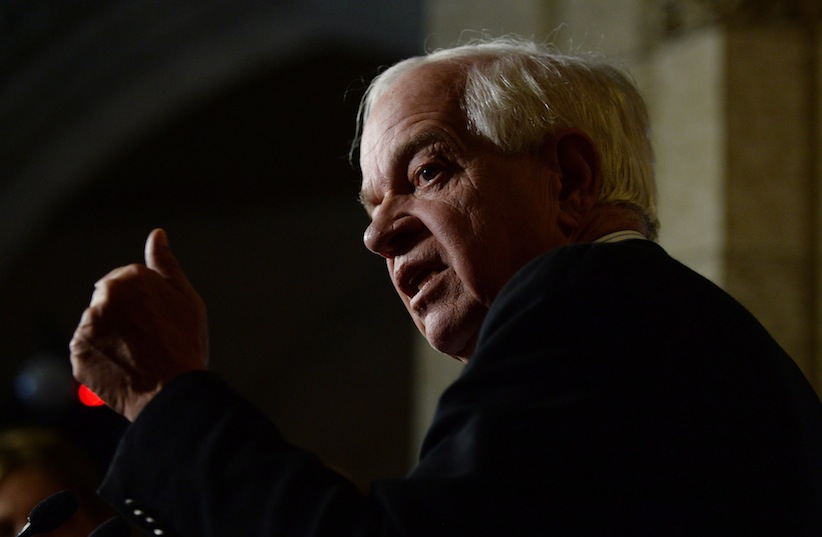

Among Justin Trudeau’s cabinet ministers, John McCallum had achieved a unique status by the time the Prime Minister was shunting him off last month to become Canada’s next ambassador to China. As immigration minister, McCallum, 66, had successfully spearheaded the bringing of nearly 40,000 Syrian refugees to Canada in a hurry, in the process emerging as the grandfatherly face of Canadian warmth in a cold world.

But listen to the unexpectedly frosty edge his voice took on when Maclean’s interviewed him last fall, a few months after Trudeau’s celebrated Syrian refugee project was effectively over, by which time McCallum had turned his attention to more pragmatic policy-making. “Yes, Canadians are generous, but that generosity is not unlimited,” he cautioned. “Canadians will accept immigration, but largely for economic reasons. A certain number of refugees, but going forward the emphasis will be more on immigrants who can quickly contribute to the Canadian economy.”

That cold-eyed appraisal of how Canadians really size up newcomers might sound at odds with the admiring reviews of Canada’s welcoming nature often aired these days in the international media. But a new survey commissioned by the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada backs up McCallum’s no-nonsense assessment. It finds that Canadians aren’t much different from Europeans or Americans when it comes to attitudes towards immigration.

“Whatever is driving Canada’s exceptionally positive history of immigration and integration over the last half century, it does not appear to be an exceptionally tolerant public,” concludes University of Toronto political science professor Michael Donnelly, who analyzed the survey of 1,522 Canadians, conducted by the polling firm Ipsos last month, for a conference the McGill institute is holding in Montréal later this week.

The survey probed how well Canadians grasp federal immigration policy, and what they like and don’t like about it. Compared with results of surveys in European countries, Canadian views were generally middle-of-the-pack. For instance, asked how much they agree or disagree with the statement that “The government should be generous in judging people’s applications for refugee status,” Canada’s generosity ranked ninth out of 22 countries, only a notch better than Britain and modestly ahead of Germany.

Compared with Americans, Canadians come off as, at best, only slightly more enlightened. One set of questions asked those taking the survey to make choices among possible immigrants. Like Americans in similar surveys, Canadians favour those fleeing persecution or seeking to be reunited with family members already here, over those just looking for a better job. And, not surprisingly, Canadians tend to prefer letting in those who are well-educated and already speak English or French.

But assumptions about race and religion figure in, too. Despite Canada’s image as a model of multiculturalism, a hypothetical immigrant from Sudan was about eight per cent less likely to be chosen by the survey respondents than a German with the same profile for education, occupation and language skills. In a parallel American survey, the corresponding difference was 10 per cent.

But if Canadians’ attitudes towards immigrants look surprisingly similar to those of Americans or Europeans, that doesn’t mean Canada’s reputation for doing a much better job at integrating newcomers is undeserved. It just means, as Donnelly suggests, that the explanation for Canada’s success can’t just be that Canadians have learned to be more broad-minded.

On the contrary, Donnelly sees in the mix of Canadian attitudes potential for the same sorts of populist, blame-the-immigrants sentiments that have bubbled up in the U.S. and Europe. “It’s certainly possible to imagine the rise of an anti-immigrant party or an anti-immigrant movement,” he says.

Why hasn’t it happened, then, at least not as a prominent force in national politics? Donnelly points to the research of a colleague, University of Toronto political science professor Phil Triadafilopoulos, who shows how immigrant voters are too important in Canadian elections for a party to succeed by alienating them. In an interview, Triadafilopoulos said Canada turns new immigrants into citizens, and thus voters, more quickly than other comparable democracies. “They don’t remain outsiders,” he says. “Politically, they become insiders very quickly.”

That crucial fast path to becoming voting citizens matters even more, Triadafilopoulos adds, because of settlement patterns. Immigrants to Canada tend to gravitate to urban and suburban centres, notably in and around Toronto and Vancouver, in strategically crucial ridings. Add to that Canada’s distinctive political system—with three or more parties vying in a winner-take-all contest for each seat, often splitting the vote in volatile ways—and no smart campaigner is likely to write off immigrant voters by running on an anti-immigrant message.

If Triadafilopoulos and Donnelly are right, Canada’s track record for embracing immigrants is less a matter of popular sentiment than political strategy. John McCallum—who for 17 years represented the suburban Toronto riding of Markham-Thornhill, where the path to election victories always ran through predominantly Chinese and South-Asian communities—would understand.