A Montreal hockey dynasty’s forgotten champions

From 2017: Among the last of a mighty team, these two prairie boys named Paul now live in anonymity in Barrie, Ont.

Canadian hockey player Red Kelly (left) of the Detroit Red Wings battles with Paul Masnick of the Montreal Canadiens for an airborne puck while Red Wing Marty Pavelich (right) skates in to join the action during the final game of the Stanley Cup in Detroit, Michigan, April 16, 1954. Detroit went on to win the game and the Cup. (Bruce Bennett Studios/Getty Images)

Share

On April 16, 1953, the Montreal Canadiens defeated the Boston Bruins, 1-0 in overtime, to win the Stanley Cup. On the roster of les Glorieux were two young sons of Saskatchewan who spoke no French but who shared an apostle’s name.

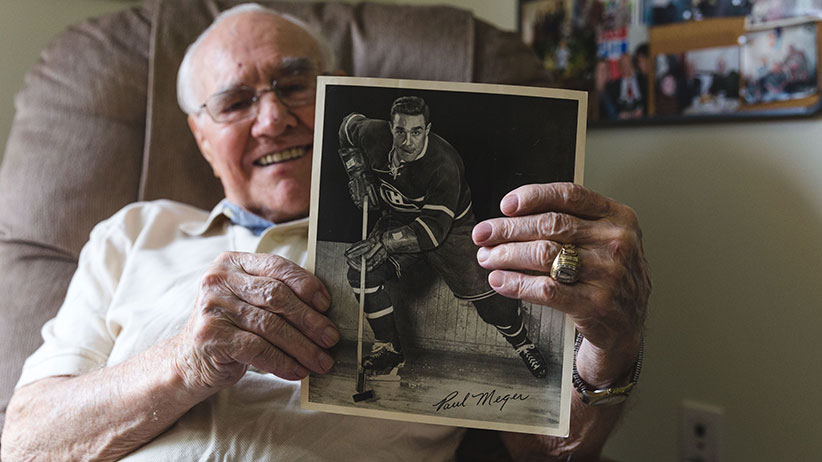

They were Paul Meger, born Feb. 17, 1929, and Paul Masnick, born April 14, 1931.

Sixty-four years later, by coincidence and the grace of angels, Paul Meger and Paul Masnick both live in Barrie, Ont. Meger is a resident of a retirement home, where the staff know him as “Big Paul, who used to be a hockey player,” even though he never soared higher than five foot seven. Masnick dwells alone in a tower overlooking Kempenfelt Bay, where his days revolve around playing penny stocks and listening to Rush Limbaugh. Occasionally, he ventures down to Toronto to visit his 79-year-old girlfriend.

And then, to sleep—“I sleep on the floor!” enthuses Masnick, a Stanley Cup champion who never once has signed an autograph for money. “It puts all your muscles and joints in balance. That’s why I’ve lived so long!”

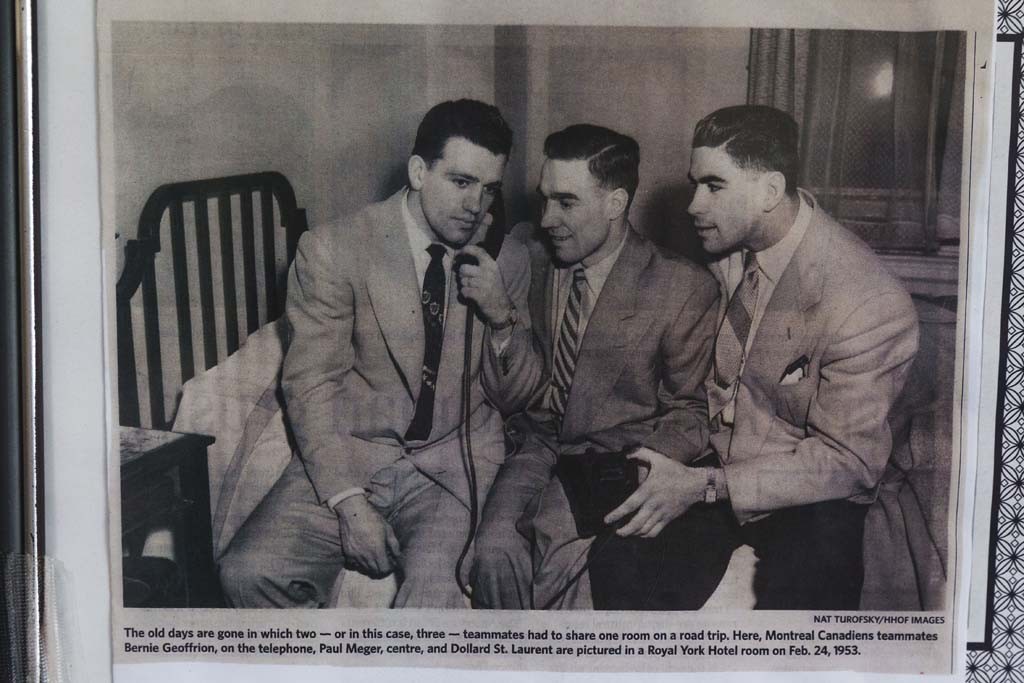

Nearly everyone else from the ’53 Habs, save a bit player or two, is dead. Plante, Lach, Geoffrion, Moore, Béliveau, Harvey, Olmstead, the Rocket—the best on the ice were taken first, leaving the little-remembered.

“The last time I looked at our Stanley Cup picture,” says Masnick, who registered one goal in the finals that year but played only four full seasons in the six-team major league, “there were only four of us left. I don’t even think about because it’s so depressing.”

“Everybody’s gone,” Masnick says. “It’s like we’re in a different time zone. I walk down the street and people pity me ‘cause I’m so old. I go on the bus and people get up and give me their seat but I don’t need it. I’m fine, but you can’t hide age no matter how much money you spend. My philosophy has always been there’s no wealth, there’s only health. If you don’t have health, you’re bankrupt. Nobody gives you health. You must earn it with discipline, diet, and exercise. My mind’s still strong while so many other guys are wavy.”

Paul Meger’s earliest memory is of watching the family homestead in Watrous, Sask., burn to the ground, leaving only a cast-iron stove amid the ashes.

Meger, one of eight sons of a German-speaking immigrant family—a sister died at birth—was 14 when a military veteran who bought milk and butter from Paul’s mother donated a carton of clothing and what-nots to the struggling clan. In the box was a pair of skates. Meger never had played a game of hockey in his life, but this soon changed.

“We went in the woods and cut crooked branches for sticks,” he says. “We cut our pucks off a wooden bar.” By age 17, Meger was a Barrie Flyer with a Grade 7 education who never again would attend school. The next two seasons, still on Kempenfelt Bay, he averaged a goal a game.

“I had some pretty good years,” he beams now. “But then I lie a lot.”

At 20, he was a Buffalo Bison; at 21, dark-haired, beautiful and already married, he was a Montreal Canadien, sharing an all-tyro forward line with 19-year-old Jean Béliveau and 20-year-old Joseph André Bernard Geoffrion.

In 1951, a goal by Meger put the Canadiens ahead in the third period of the fifth game of the Stanley Cup final against Toronto. But then Tod Sloan tied it for the Leafs with 32 seconds to play and a kid named Bill Barilko scored the last goal of his life in overtime.

Two years later, Meger had just turned 24 when his name was hammered onto the Stanley Cup.

A year and a few months later, his skull cracked and his brain gravely sliced by another player’s skate, Paul Meger would be given up for dead.

In the off-seasons, Paul Masnick attended the University of Minnesota and earned a business degree. He wound up going door to door on behalf of a manufacturer of industrial vacuum cleaners. This made him comfortable for life.

Money always was important to Masnick, who once declared himself a free agent when Frank Selke, the Canadiens’ sage and implacable manager, offered him a measly $300 bonus to sign on for another season.

“I was the hot junior from the Regina Pats,” he says of his earliest days. “Selke threw three hundred on the table. A guy told me, ‘Don’t sign now, wait ‘til the season’s over, go to training camp in really good shape, then make a deal.’ ”

As a Canadien, Masnick earned $7,000 one year and $8,000 the next, plus a two-grand bonus. He went to Europe and bought a Mercedes-Benz for twenty-two hundred. Those were the days.

“I’m gonna put you on Gordie Howe tonight,” Coach Irvin told Paul Meger one time. “Do you mind?”

“Mind?” Meger yelps now. “I think I got the puck out of our end once in the whole game, and when I headed back to the bench, Gordie said ‘Way to go, kid.’ ”

“They thought I was a terrible skater because I started so late,” Meger says. “I remember asking Hap Emms once, ‘Why did you keep me?’ ” (Emms was the doyen of hockey in Barrie and the man who would set Meger up in the home appliance business. Meger also worked as a repairman for Sears.)

“He said, “‘You weren’t very good, but God, you were trying.’ The biggest thing was, I didn’t know how to be afraid.”

On Nov. 7, 1954, Meger, a popular young regular for the most venerated hockey team in the universe, got flipped in a scrum during a match in Boston and the skate of a Bruin named Leo Labine—who also had been a Barrie Flyer; who also worked for Hap Emms’s electrical company—came up and accidentally cut him above the right ear.

“They stitched me up and I would have gone back out there,” Meger says, “but Béliveau came over to the bench and said, ‘There’s blood all over the ice,’ and Irvin told me, ‘Son, you’d better take off your equipment.’ ”

By the time Meger reached a Montreal hospital—after the long, jostling trip by rail from Boston—it was clear that Labine’s skate had sliced into the brain itself, some of which was oozing through the wound. He would undergo four perilous operations, the last at the hands of Dr. Wilder Penfield, the most eminent neurosurgeon of the age.

“He told me, ‘I’m going to take out a little piece of your brain, like a hen’s egg,’ ” Meger recalls. “I said ‘How many times have you done an operation like that?’

“He said, ‘Just yours.’”

“Do the people in your building know who you are?” Paul Masnick is asked.

“No! I don’t talk about it. If they knew, they’d say, ‘Look how slow that guy is walking. Look how he’s dressed.’ If they knew, I wouldn’t have my freedom. Freedom means more to me than anything.”

“Dickie Moore, he died and I didn’t go to the funeral. Béliveau, he died and I didn’t go to the funeral.”

He says that he has not seen or spoken to Paul Meger for more than 60 years, even though they live a mile apart. He doesn’t have a television and cannot name all 31 NHL teams. Who can?

One team he does know is the Vancouver Canucks, who just re-signed a defenceman named Erik Gudbranson for US$3.5 million for one season. “If Frank Selke came alive today, he’d see that and go right back in the hole,” Masnick says.

Gudbranson, whose name is not on the Stanley Cup, is dating the granddaughter of Masnick’s girlfriend. When the girl asked what he might like as a gift to celebrate his new contract, he asked for a photograph of Masnick as a Montreal Canadien.

“Can you imagine Sidney Crosby selling vacuum cleaners door to door?” Masnick is asked.

“No,” says the champion. “He doesn’t need to.”

“You know, I played on a line with Jean Béliveau and Boom Boom Geoffrion, with Jacques Plante in goal—that’s pretty good, eh?” Paul Meger smiles.

“You know the best part? I’m here to talk about it. I remember I asked Doctor Penfield, ‘Can you please take out the part of my brain that worries?’ I was worried—am I going to walk? Am I going to talk?

“I thought, ‘If I ever get out of here, I will never have a bad day.’ ”

Twelve hundred men have played for Stanley Cup-winning teams.

These are two of them, among so many millions who wished.