Awe and humility in the face of the eclipse

The alignment of celestial bodies drew cries from a crowd in a Vancouver park. One woman projected it through her colander.

Share

A man called Lief balanced a pair of binoculars pointed behind him, directly at the sun. Behind him, a woman named Janet—they’d met moments earlier—held up a piece of cardboard, casting a shadow. All around them, in Vancouver’s Vanier Park, one of the country’s better viewing spots for the solar eclipse, a cry went out when the crescent shape of the partially blocked sun appeared, projected onto a screen in front of Lief.

“We could be anywhere, said Janet, a resident of Vancouver’s North Shore. “But we’re here because your sense of wonder is magnified when you’re surrounded by community.”

If you looked closely, crescents were suddenly appearing everywhere: in the pavement beneath a densely shrouded fir tree, in the shadow cast by a straw hat. An elderly woman carried a colander, taped over in places. Beneath it, dozens of crescents appeared, forming the shape of the peace symbol.

Just as quickly, the almost perfect crescent moon began to rotate. Suddenly, it looked like the mouth in a happy face. Its colour had gone from white to a burning, blood orange.

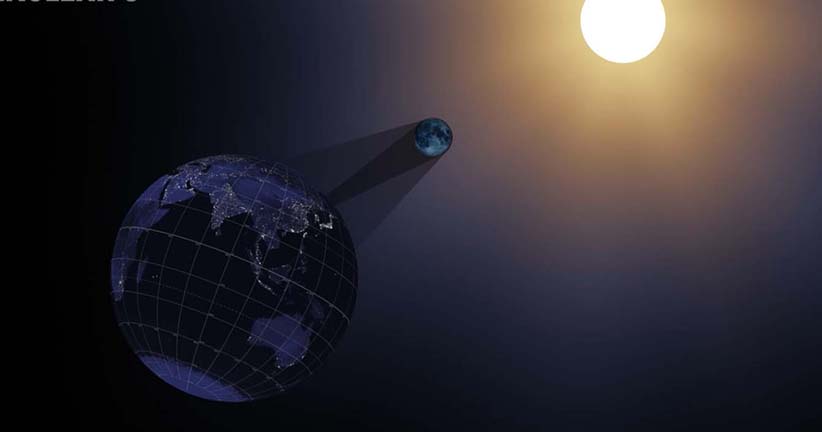

An eclipse is a syzygy, an alignment of three celestial bodies. But none here seemed to have imagined the cold this would create on a such a hot, August day. For several minutes leading up to 10:21 a.m. PST, when the moon blotted out 86 per cent of the sun, people in the crowd began to point to goosebumps on their arms and legs. Some were shivering.

All around, the light began taking on a grey-blue sheen, as if someone had dimmed the lights. No one needed their sunglasses. A woman began to sing. Behind her, someone wondered aloud how the ancients would have experienced the sudden darkness and cold. Some described feeling overcome by a sense of humbleness.

We are like ants, scrambling about, jockeying for position, obsessed with the day’s news, our dinner plans, explained Vancouver’s Susan Stewart. “Down here, our minds are focused solely on our troubles. But when our main source of energy, of heat, of survival is blotted out, our interests turn, suddenly to the heavens.

“We are reminded that we have no control. Our troubles feel so irrelevant. Mouths agape, we can do nothing but stare in wonder—and hope our world will return.”