How a grieving mother helped create a DNA database to identify Canada’s missing

After Judy Peterson’s daughter disappeared 27 years ago, she poured herself into a campaign to create the more integrated, country-wide DNA database. Here’s how it led to a Quebec mother finding her son.

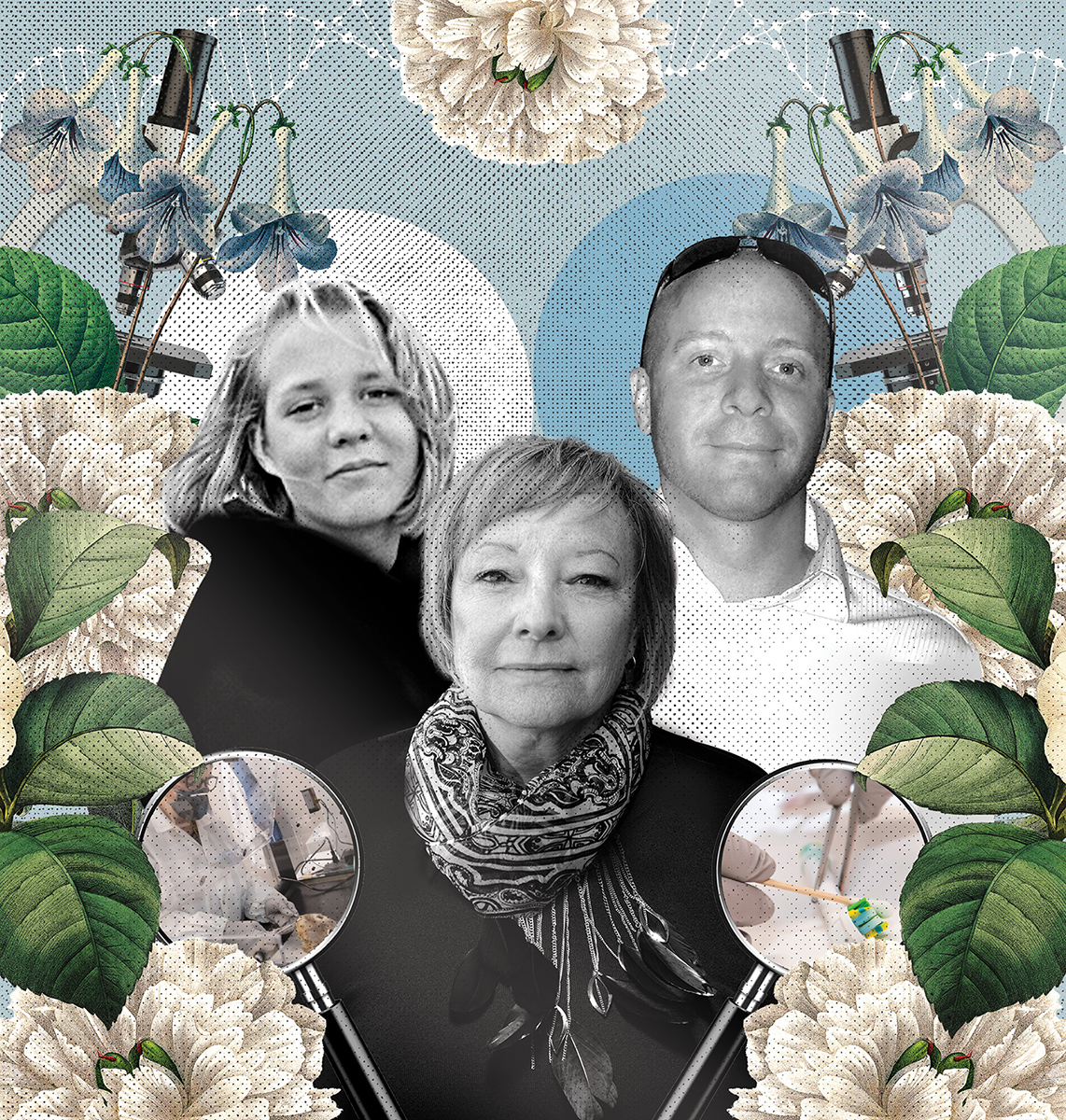

Peterson’s (centre) search for her missing daughter Lindsey (left) helped locate Audy (Photo illustration by Natasha Cunningham)

Share

Because Judy Peterson lost her daughter, Monique Gamelin found her son. The tale of how the two mothers’ lives became so intimately interconnected began more than 27 years ago on a hot long weekend in August when Peterson’s daughter, Lindsey Nicholls, took a walk along a rural road on the east side of Vancouver Island, heading toward the town of Comox, B.C. Lindsey—artistic, athletic, blazingly funny—was 14. She was never seen again. Police suspect foul play.

In 2000, after seven years of fruitless investigations, Peterson made a jarring discovery. While Canada had just established a national database to store genetic profiles from criminal sources, including crime scenes and some convicted people, DNA from those who had gone missing and from unidentified human remains was not included. She was gutted. B.C. had a long-standing DNA repository for the lost and unidentified. But if Lindsey had ended up in another province, Peterson might never learn her fate.

Peterson, who now lives in Sidney, B.C., poured herself into a passionate campaign to change that. It took 18 years and countless hours of lobbying lawmakers, stickhandling federal privacy concerns along the way.

READ: Bruce McArthur case: How a hobby database of missing persons uncovered a serial killer

“Working on that was cathartic in its own way, as it felt as though I was doing everything I could to find her,” she says.

In March 2018, the federal statute known as Lindsey’s Law came into effect. It allows police, medical examiners and coroners to submit DNA profiles of lost people and unidentified human remains into the larger national repository. Once there, a software program searches for matches, typically every day, and relatives of those who have gone missing can also submit their DNA.

After that, Peterson waited for police and pathologists to build up the database by submitting DNA profiles of unidentified remains; for relatives of the lost to learn about the program and donate their DNA; and for the first matches to prove to her that the system would actually identify the missing.

Fast-forward to October 2019. Gamelin, who lives in Sudbury, Ont., got a phone call from her daughter who, in turn, had received a call out of the blue from Const. Gord Fraser of the Calgary Police Service. Fraser was investigating the death of a man whose body had been found in a makeshift camp along a river valley in Calgary two years earlier.

It was a baffling case. While police were able to tell that the man had not been murdered, they had no way of identifying the body, which had lain undiscovered in a tent for months. There were few belongings except a badly damaged cellphone with a SIM card cut in half. No fingerprints. Even height and weight were difficult to estimate.

“It was the ultimate mystery,” Fraser says.

Because Lindsey’s Law had not yet been passed, Fraser began with old-school police legwork: laboriously investigating people across Canada’s patchwork of police agencies who were reported missing. At one point, he tracked a promising lead all the way to Quebec, only to solve the case of a different missing man. So he turned his attention to the damaged cellphone, asking his digital forensics team members to extract anything they could.

By then, Lindsey’s Law was in force, and Fraser also asked the medical examiner to make a DNA profile of the man. He submitted the sample to the fledgling DNA program and Ingrid Muhlig, who works with the DNA profiles as part of the National Centre for Missing Persons and Unidentified Remains, helped investigate any matches.

Two things happened at almost the same time. The cellphone spilled a few of its secrets, including some text messages, pictures of a man in a tent, a few email threads and a list of contacts. Then Muhlig came back with a tentative match from a man in Quebec who had an existing DNA profile in the criminal part of the repository. Quebec police tracked down his family and passed along the information to Fraser, who called Gamelin’s daughter.

Gamelin last saw her son, Marc Audy, in the fall of 2012 as he left her home in Sudbury to catch a midnight bus. Tall, blond and unfailingly kind-hearted, Audy had often been out of touch for long periods. But never this long. Gamelin had not reported him missing but she suspected the worst.

“After a while when you don’t have any news, you figure out that something has happened,” she says.

She had watched her dearly loved son struggle with addiction for most of his life. He’d had therapy, and at one point remained sober for three years. Then he returned to drugs.

“He was my baby,” she says.

By late October, two years after the case began, Fraser and Muhlig had a definite match. The man in the tent was Audy, dead at 37.

“The most important thing is that we won’t die not knowing where he was and how he died,” Gamelin says. “My god, I really appreciate all the work they did to find out who he was.”

Audy’s death is the first case in Canada to be solved using information from the national missing persons DNA program set up because of Lindsey’s Law. Without that program, his fate would have remained a mystery forever, Fraser says.

“Canada’s such a vast country that using traditional investigative techniques doesn’t always work,” he says, adding that he expects many more uncrackable cases to be solved using the databank over time.

Already, another 20 cases have been matched for a total of 21 as of mid-December, the RCMP says. The second person identified was Cheyenne Partridge, a 25-year-old who went missing from Edmonton in 2016. Some of her remains were discovered in Saskatchewan in 2018. Police are still investigating.

In December, police announced that they had identified the body of Cheryl Pyne, who went missing in New Brunswick in 2004 at the age of 27. The RCMP requested DNA from a family member in November in order to make the match to an unidentified body found in Saint John, N.B., in 2012. A man had been sentenced to prison for life in 2009 for Pyne’s killing.

Cpl. Kelly Bates of the Saskatoon RCMP’s historical case unit, who led the investigation of Partridge’s remains, says DNA offers investigators new tools to provide closure for traumatized families who have lost loved ones. “DNA doesn’t by itself solve a case or tell a story,” he says. “But it’s an important piece of telling a story.”

And of course the bigger the repository, the better the chance for a match. The repository now has genetic profiles from 102 missing persons, 791 relatives of missing persons and 226 unidentified human remains. Those numbers have been climbing steadily. In addition, the database contains DNA from about 450,000 convicted offenders and genetic profiles of more than 180,000 unidentified people from crime scenes.

Although she unleashed the whole program, Peterson is not provided details of any of the cases from the RCMP. She was astounded to hear from Maclean’s about Gamelin and her son. And thrilled.

“This is what I’ve been waiting for,” she says.

It gives her added hope that the system she helped set up may even, one day, bring news of her beloved Lindsey.

This article appears in print in the February 2021 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Losing a daughter, finding a son.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.