How Canada’s housing crisis is fuelling violence on our public-transit systems

“I’ve worked in public transit for nearly 40 years, and I’ve never seen things so bad”

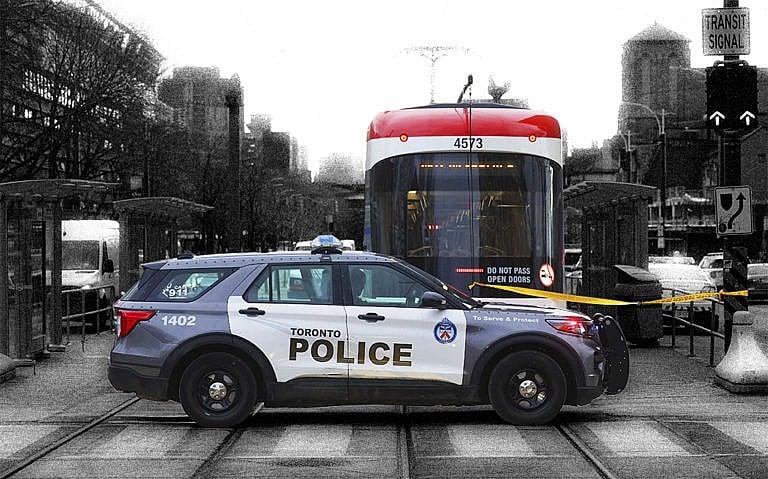

Transit union president John Di Nino sees a link between rising violence and greater societal conditions throughout Canada (Photo courtesy TTC/Getty)

Share

I started my career in public transit when I was 19 years old, in 1986. I mostly worked as a mechanic in Toronto’s subway stations, far from the public, so I didn’t have to worry about my own safety on the job the way bus drivers and train operators sometimes do. That same year, I became a steward with the Amalgamated Transit Union, which represents more than 200,000 members working in transit systems across Canada and the U.S. In 2018, I ran to become the union’s president, hoping to take what I’d learned through decades of training and advocacy in my own city and make change on a national level. I didn’t know then that a big part of my job would be to grapple with a nationwide crisis of crime and violence on public transit.

The number of violent incidents had been on a slow increase for years, but just before I became president, it felt like something really changed. In February of 2017, Winnipeg bus operator Irvine Fraser was stabbed to death by an unruly passenger he removed from his bus. The news landed like a gut punch for me, and for every transit operator who’d ever dealt with a troublesome passenger.

Around that time, there were about 2,000 operator assaults annually in Canada. When the pandemic hit, it looked at first like those numbers were dropping—but that was just an illusion caused by plunging ridership. The number of assaults relative to ridership was actually trending upward. Then, as things started to reopen and riders returned to transit, the number of violent incidents grew dramatically across the country, in communities big and small. It didn’t matter where you were. Transit union representatives in Saskatoon recently reported a huge jump in driver assaults—38 last year alone, more than in the preceding four years combined. In Canada’s biggest city, the Toronto Transit Commission logged 1,068 violent incidents against riders in 2022, a 46 per cent increase compared to 2021.

The assaults range from relatively minor, like verbal abuse and spitting, to the headline-making ones. Last February, two TTC employees—a bus driver and a subway operator—were stabbed in separate incidents in the span of a week. In Edmonton last April, a man punched an elderly woman at a light-rail station, causing her to fall onto the tracks. In January, two bus drivers were threatened with guns in separate incidents. In Calgary last November, a woman was injured in a hatchet attack at a train station. Days later, a man was shot by a flare gun and set on fire at the same station. A few months ago in London, a man tried to stab a bus driver on the job. The perpetrator was released, and every day since, that operator has been worried about going to work. Is that person going to get back on my bus? Is that going to happen to me again? Is it going to be worse this time?

A few of these assaults have been tragedies. Two passengers were murdered in the Toronto transit system last year; one was a woman set on fire on a subway platform in June, and the other was a woman stabbed in a random incident in December.

Why have things become so bad, so fast? Ultimately, it’s because this isn’t a transit issue—it’s connected to much deeper social stresses. The transit-violence epidemic is an offshoot of other problems that have gone unaddressed, in particular our growing national housing crisis.

READ: How Toronto’s housing market is transforming the rest of Canada

Many of these assaults have been committed by vulnerable or troubled people—people with mental-health issues, people on the edges of society. And as housing affordability has rapidly worsened throughout the pandemic, there are more and more people in this kind of distress on our streets and taking shelter in our transit systems—people who have nowhere else to go. There are no statistics or hard numbers on this, unfortunately, but many of those who work with the most vulnerable in our society have noticed the same pattern: people finding refuge in bus shelters, train stations and transit vehicles.

The response by governments and employers has been overwhelmingly reactive, not proactive. In January, the City of Toronto announced it would deploy 80 additional officers throughout the TTC in an effort to address violence. Six weeks later, the city announced the end of those measures. They only responded once the crisis was in full swing, without funding in place to support it, and then it was over. Like the crisis itself, this weak response isn’t just a Toronto problem. I have yet to see any level of government, anywhere, make any concrete plans to address the issue, meaning short-term security fixes, plus long-term investments in housing and health care. These are discussions that need to happen—lives are literally on the line.

So is the future of our transit systems. Public transit is a mobility right for all Canadians, and if we’re really a society that’s concerned about climate change, then we need to put our best foot forward with public transit. But people will stay away if they fear for their safety. As for operators, I’ve never seen morale as low as it is now. Our co-workers are being threatened, punched, knifed and shot.

RELATED: My mortgage is about to go up by at least $1,000 a month

And there’s a lack of accountability and transparency from transit agencies themselves. For example, when the TTC recently released data on assaults, it focused on passengers only, and didn’t say how many attacks were against staff. We also need a better reporting mechanism for specific incidents so we can more accurately identify the underlying causes. What are the triggers for these incidents? How are we gauging homelessness? How are we gauging addiction issues? If we’re going to understand the true scope of this problem—as well as the real risks to our members—we need agencies to do a better job of reporting the circumstances surrounding violent crimes.

This is personal to me in multiple ways. My wife was critically injured in a mass shooting last December that killed five residents of our condo building. The perpetrator was dealing with mental-health issues and fell through the cracks—and then tragedy struck. My personal experience with violence reinforces my view that we have to do better in terms of the social services we provide, the tools we use to mitigate threats of violence, and in making sure people with mental-health issues can access the care they need. They can’t do it when they’re living on the streets or seeking refuge in train stations and bus shelters, pushed into ever-more desperate living situations.

I did a press conference on transit assaults last month at Vaughan Metropolitan Centre Station. As I entered the station, there was a person there who was obviously in some kind of crisis. I asked one of the TTC workers to call for assistance, and two York Regional Police officers were dispatched. They took the man, put him back on the subway and moved him back into the system—back to Toronto. That’s not support. That’s not dealing with the problem. That’s getting the problem out of your jurisdiction.

That’s why I have called for a national task force to address the violence. We need to bring all the stakeholders together—the unions, transit employers, municipalities, police, transportation ministers—to hear directly from front-line staff. We need to figure out how to mitigate the risks, then use that as a template to better protect staff and riders across the country. We need the Canadian Urban Transit Association to facilitate these discussions and the ensuing next steps. We need the Federation of Canadian Municipalities to understand the necessity of what we’re trying to do to rebuild public transit in their sectors. We need the provincial and federal governments to assist us with operational dollars to implement the practices, training and supports we identify. And we need to talk about the housing crisis, and the mental-health crisis and all the ways they intersect with public transit.

—As told to Caitlin Walsh Miller