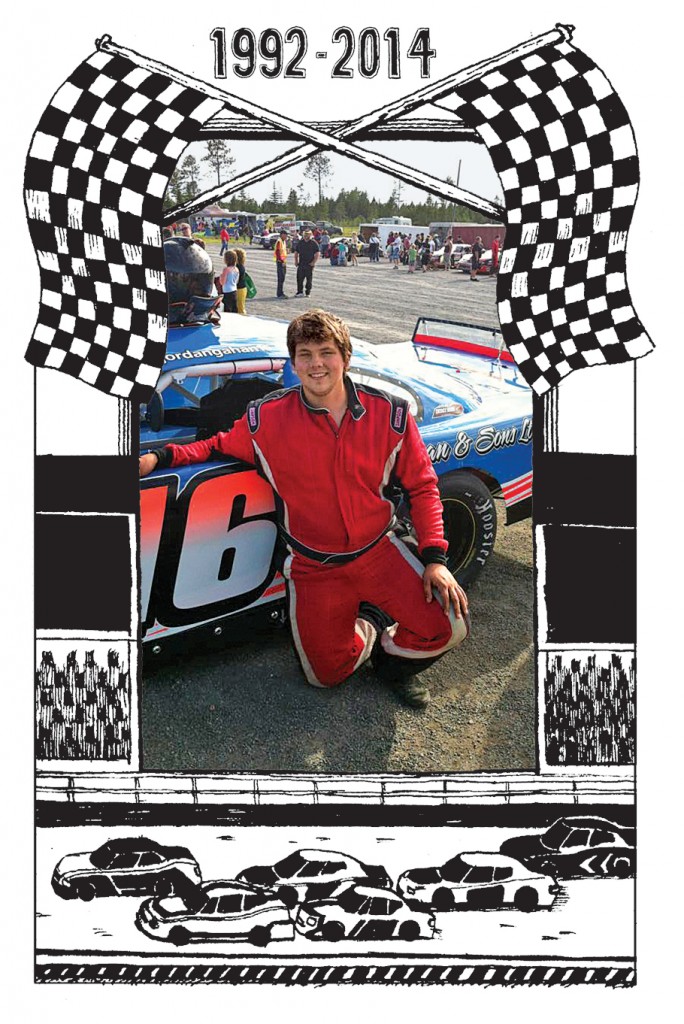

Jordan Paul Gahan, 1992-2014

A race-car driver like his beloved father, he moved out west to finance his dream

Share

Jordan Paul Gahan was born in Fredericton on Oct. 23, 1992, the son of Paul Gahan, a heavy-equipment operator, and Leica Gahan, who helped run the family construction business. Big-eyed and busy, baby Jordan was the third of four brothers whose names all begin with “J.” (Joshua and Joel came before him, and Jonathan after.) Although he didn’t arrive in this world gripping a steering wheel, it sure seemed that way. “He was born to race,” Joshua says.

Jordan was still in diapers when his father brought home a small four-wheeler and plopped him on the seat. The toddler immediately cranked the throttle. “I had to tie a rope on the back and run around behind him, hanging onto it so he wouldn’t get away,” Paul recalls. With a gigantic grin on his face, Jordan spent more time peeking back at his dad than paying attention to where he was going.

A smart kid with gifted hands, Jordan was far more comfortable in a garage than a classroom. He shared his dad’s love affair with powerful race cars, and if Paul was tinkering with an engine or buffing a hood, Jordan was never far away. “He was his father’s shadow,” Paul says. “He always wanted to be like his dad.” Jordan was still in lower school when Paul joined the racing circuit at Speedway 660 in Geary, N.B., the only track in the Maritimes that runs a weekly pro stock series. Though he wasn’t old enough to be a member of his father’s crew, the team still managed to sneak Jordan into the pit. He soaked up everything.

“He was very passionate about learning,” says his cousin, Travis Gahan, “not so much academic-wise, but through talking to people. He was a very social guy, and if you met him, he’d want to know everything about what you did and your opinions on things. He’d give you his opinion, for sure, but he’d want to know yours.” Like the cars he adored, Jordan’s mind was forever racing. “His personality was just ‘go, go, go’ at all times,” says Jake Bryden, a close friend. “He went a million miles a minute, doing five tasks at once. He was one of a kind.”

In Grade 12, Jordan actually built his own stock car—a blue Chevrolet Impala with No. 16 painted on the doors: “Sweet 16.” That spring, he followed his dad’s treads to Speedway 660, where he raced so well on Saturday nights, he earned the division’s 2010 “rookie of the year” award. It was a season of highs and lows, he told a local reporter. “But my mom, who is the most positive person I know, encouraged me to keep working hard and believe in myself,” he said. The next year, Jordan earned a rare scholarship to Race 101, a North Carolina program that teaches aspiring young drivers the nuances of the sport, from technique to marketing to media relations. Out of 250 applicants, Jordan was among only 18 to be accepted.

His dream was to be a full-time driver, but racing was not his only passion; Jordan enjoyed hunting and fishing almost as much as capturing checkered flags. And he was madly in love—with a girl, Natasha Rousselle, who enjoyed all the same outdoor pastimes. “They were dating, but they were also best friends,” Jake says. “He’d go fishing, and she’d go, too. She went to the track. They were inseparable.”

The 2013 season proved to be Jordan’s most frustrating. Although he had the support of numerous sponsors, he didn’t have the funds to buy what he truly needed: a completely new car. So when an Edmonton construction firm offered him a lucrative job out west, operating heavy equipment, Jordan couldn’t resist; in his mind, he could bank enough money to replace his race car and return to Fredericton for the 2014 campaign. “This has been a very tough decision, but the 2013 season is over for the 16 car and myself,” he wrote on his Facebook page last August. Natasha joined him for the long drive to Alberta.

The couple shared an Edmonton apartment with Travis and his girlfriend. By fall, Jordan accepted a new job with a company doing work in the oil sands; he flew into Firebag, just north of Fort McMurray, to work a few days at a time. “He was talking about having a family, buying a house,” his dad says. “Racing was still his passion, but setting up his life was even more important.”

March 14, a Friday, was supposed to be one of Jordan’s final shifts; he and Natasha were planning to head back east at the end of the month. He was behind the controls of a trackhoe that afternoon, operating in a pit, when the machine broke through a patch of ice. Jordan, 21, did not survive.