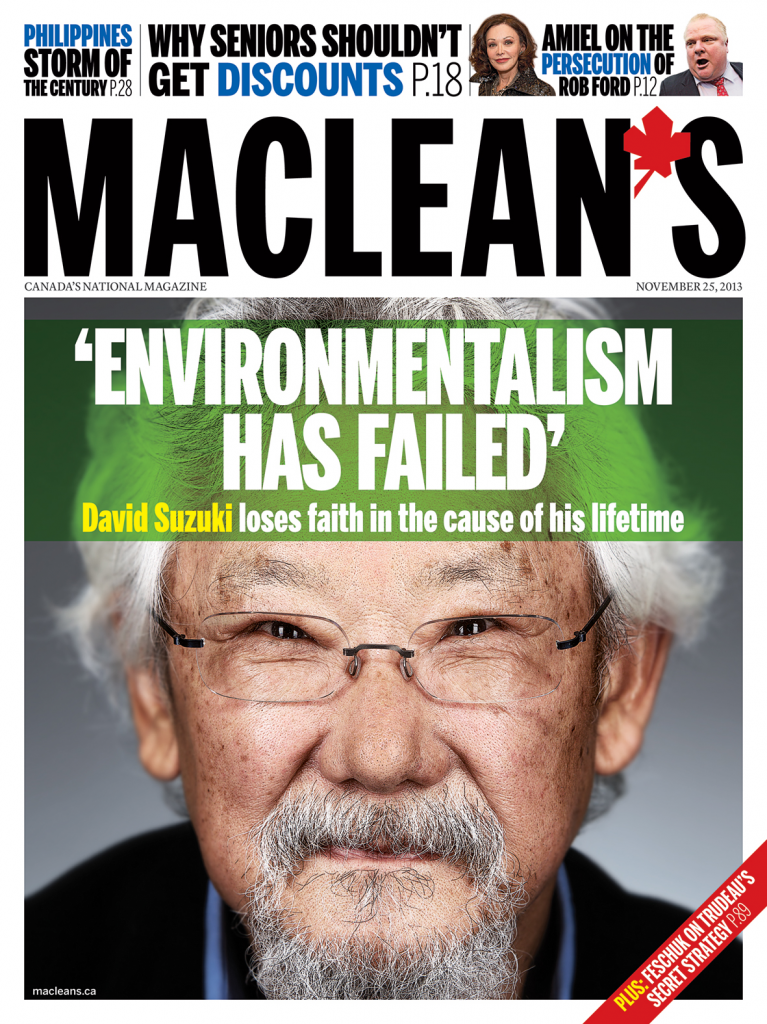

The nature of David Suzuki

In his final stretch, the world’s most famous environmentalist is beset by doubts and doubters

Photograph by Brian Howell

Share

David Suzuki has launched a cross-country tour. In this piece from November 2013, he spoke about his life and legacy:

David Suzuki has finally realized that there are some hills he can’t climb. Now 77 years old, dealing with gout and other indignities of age, the world’s best-known environmentalist recently traded in his mountain bike for one with an electric motor. The ride from his waterfront home in Vancouver’s Kitsilano neighbourhood to his office on West 4th Avenue, isn’t very long, but it’s mostly uphill. And although it has never been enjoyable, the effort suddenly started to seem unbearable this past summer. So he sought technological assistance. “God, at my age, can’t I cheat a little?” he asks.

The small admission of defeat came just a few weeks after a much more potent reminder of where he’s headed. On July 9, Tara Cullis, his wife of 40 years, and 13 years his junior, suffered acute heart failure while swimming in the ocean off their home. She made it to shore, where someone on the beach called 911, and then called their house. Suzuki, barefoot and wearing a Yakuta, a traditional Japanese housecoat, made it to her side before the ambulance arrived. She survived, but the road to recovery has been rocky. Suzuki has drastically cut back his speaking engagements and travel. The couple has sworn off alcohol and salt. It has been a time for reflection for both of them. “The reality is that at my age, I could kick the bucket tomorrow,” says Suzuki. “Everybody goes, ‘Oh, no. You’re going to live into your 80s.’ But the reality is that I’m living in the death zone and I accept that.”

His scientific career began in the late 1950s; his media one, a decade later. Since 1979, he’s been the face of CBC’s The Nature of Things, an internationally distributed science program that’s now in its 53rd season. Suzuki’s official CV runs 17 pages. It lists dozens of academic and broadcasting awards as well as his 25 honorary degrees. Now a professor emeritus at the University of British Columbia, he has authored or collaborated on 50 books. In 2011, Reader’s Digest anointed him as its “most trusted Canadian.” And this October, he topped an Angus Reid poll of the country’s most admired figures, with 57 per cent of respondents giving him the thumbs up. However, lately, he seems to have been garnering more controversy than accolades. Suzuki has come under fire for his outspoken views on immigration—that Canada is at its environmental capacity, basically. On a swing through Australia in September, he drew criticism for suggesting the country’s new prime minister, Tony Abbott, is guilty of negligence and “crimes against future generations” for scrapping a carbon tax and dismantling climate change bodies. He has stepped down from the board of his eponymous foundation, uttering dark warnings about the bullying of Canadian scientists and the federal government’s attempts to marginalize environmentalists. His critics in the media have become emboldened, savaging “Saint Suzuki” for his personal life as well as his politics.

Earlier this month, the Royal Ontario Museum put the environmental activist on “trial” as part of a new exhibit on climate change, charging him with seditious libel for a manifesto that called for an end to oil. All across Toronto, billboards were plastered with his grandfatherly image, and tag lines like “Treason or reason?” and “Radical or rational?” Suzuki eagerly embraced the pageant as an opportunity to explore questions that he’s been asking himself.

For a while now, the green movement’s chief messenger has been wondering just what he and his compatriots have really accomplished.

“Environmentalism has failed,” Suzuki declared in a dark blog post in the spring of 2012. The heady victories of the 1970s and ’80s over air pollution, acid rain, and clear-cut logging are distant memories. The oil and gas industry has never been stronger, sinking ocean wells, fracking across the continent, and going full-bore on Alberta’s oil sands. Meanwhile, the fight against climate change has come to a virtual halt, as governments around the world put the economy ahead of the environment. “We’ve come to a point where things are getting worse, not better,” he said in an interview with Maclean’s.

In the final stretch, David Suzuki is beset by doubts and doubters, both at home and abroad. During his recent trip to Australia, he sat down with a national network for a one-hour televised Q&A. It was anything but a love-in. The evening began with two hostile questions on global warming from invited dissenters. Other audience plants took him to task for his stand against genetically modified foods, statements he had made about the effect of cyclones on the Great Barrier Reef, and his views on immigration. Suzuki never lost his patience, but he seemed to wilt under the attacks as the show went on. “I’ve had a belly full of fighting. We’ve got to stop the fighting,” he pleaded at one point. The message that he has been delivering for four decades is no longer getting through. And time is running short. “I hope there’s a happy ending. That’s all I have left. Hope.”

Getting a hold of Suzuki these days isn’t a straightforward task. Although he still comes and goes as he pleases at the foundation, writes columns for its website and maintains an office in the same building, they no longer handle his PR. “It’s complicated,” sighed a spokesman. His email address is a secret. His office phone number is unpublished.

When Suzuki came to Toronto to promote the ROM trial by reading out his anti-carbon manifesto on the steps of a downtown courthouse, the press release was sent out that same morning. Even then, that didn’t stop one of his chief tormentors from trying to sabotage the show.

Ezra Levant, the Sun News Network shouting head, showed up with a camera in tow and a line of aggressive questions. When Suzuki retreated into the back of a waiting Chevy Volt and refused to come out, it provided Levant, once the communications director for Stockwell Day and long-time oil sands cheerleader, with some dream visuals. The next day, his program The Source devoted an hour to tearing down the green crusader. “We’ll trace the evolution of the man from happy, chatty scientist to a reclusive crank,” Levant proclaimed with a shark-like smile. “Increasingly paranoid, increasingly prone to conspiracy theories, and moving further and further away from true science.”

Back in 1989, Suzuki participated in a highly publicized debate with Philippe Rushton, a University of Western Ontario psychologist who had published controversial research linking intelligence to race. The crowd was squarely on Suzuki’s side and most observers thought he scored an overwhelming victory, but the experience left him leery of becoming a foil for cranks and deniers. Mindful of Levant’s tiny reach—his show airs twice a day and has a combined national audience of less than 20,000—the geneticist has steadfastly refused to agree to an interview. But that hasn’t stopped Levant from taking highly personalized shots at Suzuki on TV and in print via his column for the Sun chain. In recent months, he’s accused Suzuki of living a plutocrat’s lifestyle, citing the $8 million assessed value of his Vancouver home, and claimed that he co-owns an island off the coast with an oil company. He’s also made much hay from a talk that Suzuki gave at John Abbott College in Montreal last year, saying he charged a $41,000 fee and demanded a complement of all-girl bodyguards.

“I’ve had critics all my life,” says Suzuki. “But I certainly think the intensity and vileness of the personal attacks has changed.” Levant, who is a trained lawyer with a great deal of personal experience with Canada’s libel laws, has been careful to make most of his allegations technically factual, Suzuki says, but they’re a contorted version of the truth. The house in Vancouver was purchased for $145,000 in 1975 with a loan from Suzuki’s in-laws. For years, he and Cullis lived in the basement and rented out the top floor in order to afford it. Later on, they added a second storey and her parents moved in. Suzuki’s mother-in-law, now 95, still lives above them. “It’s not like it was an investment. It’s the crazy escalation of house prices,” he says.

As for the charge about the island, it took some digging for Suzuki to figure out what Levant was talking about. In 1986, after winning a $100,000 achievement award from the Royal Bank, he and his wife bought 10 acres on Quadra Island as a getaway property. It was part of a much larger parcel that was being subdivided. As it turns out, one of the other buyers made their purchase through a family business, a Calgary company that once delivered home heating oil, but now exists in name only.

Similarly, Suzuki allows that there is a shred of truth to the story about his Montreal talk. Presented with an offer from the college to use students from its police training course as security, his assistant wrote an email saying Suzuki preferred a more low-key approach, and noting that he regularly travels with a female assistant who clears a path through crowds by politely asking people to move aside. His appearance fee—not just for the speech, but a full day of fundraising activities for John Abbott—was about $10,000 less than has been reported, and came out of the pocket of a well-to-do Montreal supporter, not from the college’s end.

Suzuki believes the muck-throwing is part of a wider trend where experts are now being painted as adversaries. “Scientists are being portrayed by much of the power structure in politics and business as having a vested interest—that they’re just out to get more grant money by exaggerating the threats,” he says. He decided to resign from his foundation in the spring of 2012 because he feared it would be targeted for a tax audit by the Harper government and might lose its charitable status. (More than 900 environmental groups have had their books scrutinized over the last couple of years for evidence of large foreign donations or excessive spending on political activities.) “I wanted to protect the foundation,” says Suzuki. “And at my stage in life, I simply found it intolerable to have to hold back on what I say.” Although given that the organization is still branded with his name, and Cullis and their two daughters, Severn and Sarika, remain on the board, it seems to have been more of a protest than a serious attempt to distance himself.

Laurie Brown, the CBC radio host who hatched the idea of the Toronto mock trail—complete with real lawyers, a judge and a jury—senses that an element of theatre has already infiltrated the debate about the environment. “Everything has become more polarized in the last few years,” she says. “And David is a lightning rod.”

Suzuki says he likes the idea of being put in the dock for his beliefs. It reminds him of one of his favourite movies, A Man for All Seasons, the 1966 film about Sir Thomas More’s principled path to a beheading by King Henry VIII.

Suzuki has always had a short and cryptic response for people who ask how a bespectacled and slightly hippie-ish geneticist ended up as a TV star. “Pearl Harbor.” He’s a third-generation Japanese-Canadian—both sets of grandparents settled in Vancouver in the years before the First World War—and spoke only English as a child. But that made no difference in the hysteria that swept North America’s West Coast after Japan’s sneak attack on Hawaii in December 1941. Within a couple of months, the Suzuki family’s dry-cleaning business had been shut, their home and property confiscated and sold off by the Canadian government, and they were interned as “enemy aliens.” Five-year-old David, his mother and two sisters were sent to an abandoned mining town in B.C.’s Slocan Valley. His father was put to work building the Trans Canada Highway, a hundred miles to the north, for a wage of 25 cents an hour, less the cost of “room and board,” for himself and his family. Conditions were deplorable. The accommodations were cramped and filthy—Suzuki recalls waking in the morning covered in bedbug bites. Fresh food was in scarce supply. And the government hadn’t thought to provide a school for the more than 2,300 children. Although Suzuki’s memories of those years, as detailed in his two autobiographies, aren’t all unhappy ones. Left largely to his own devices in an isolated mountain community, he spent lots of time fishing and running around in the woods, developing a deep love of nature.

Prohibited by law from returning to Vancouver after the war, the family resettled in southwestern Ontario. For a few years, all the Suzukis worked as farm labourers near Leamington. When David was in Grade 10, they relocated to London, Ont., to join extended family.

In his youth, he was ashamed of his heritage. “I read in Life magazine that Asians had developed an operation to enlarge eyes and I yearned to have this done. I wanted to dye my hair brown and to anglicize my name,” he wrote in 1987’s Metamorphosis. “Self-hate was the most terrible cost of the war years for me.” Yet at the same time, the small and insular community of Japanese-Canadians in Ontario was the only club to which he felt he really belonged.

He was also driven to succeed. At his father’s behest he started entering public-speaking contests, working tirelessly to memorize his talks, and restarting from the top each time he stumbled. (It’s a technique Suzuki still uses to learn his TV scripts.) And despite the iffy start to his formal education, he became a top student, excelling at math and science.

In 1954, he won a full scholarship to Amherst College in Massachusetts, and developed a passion for the new field of genetics. After graduating in 1958, Suzuki married his high school sweetheart, Joane—one of the 10 Japanese-Canadian girls in London he wasn’t related to—and went on to the University of Chicago, where he sped through a Ph.D. in just three years. Afterwards, he took a post-doc position in Oak Ridge, Tenn., but soon found he couldn’t abide the still-segregated South.

Although Asians were accorded the same privileges as whites, the treatment of blacks enraged him. He joined the local NAACP chapter, becoming its only non-black member. When American colleges came calling, he spurned them in favour of a job at the University of Alberta.

Suzuki only lasted a year in Edmonton—the climate was too brutal, he says—but it was there he got his first experience in TV, hosting eight Open University lectures on a community station, broadcast at the crack of dawn on Sunday mornings. In 1963, he took a job at UBC, returning to his birthplace. His research on the genetic structure of fruit flies became the focus of his life. He pulled long hours in the lab, seven days a week, often spending the night in a hammock he had strung up in the back room. His first marriage disintegrated.

By the late 1960s, Suzuki had established himself as a budding scientific superstar. The Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada awarded him as one of the country’s top young minds. He was invited to teach for a semester at the University of California at Berkeley, where he discovered and embraced the counterculture. CBC Television harnessed his new persona—at once hip and geeky—first for a series of specials, then giving him his own weekly Suzuki on Science show. In 1975, he moved to radio, becoming the first host of Quirks and Quarks. A year later, he was named to the Order of Canada.

Suzuki’s strength has always been his ability to translate the world of science for the layperson, cutting through the jargon and breaking down complex ideas into digestible television bites. At the height of its popularity in the mid-1980s, The Nature of Things was drawing a weekly audience of 1.3 million, or almost 20 per cent of all Canadian viewers. And the entire series was being broadcast in 13 countries, including the U.S., with 55 more nations picking up individual episodes. That success is what made David Suzuki a trusted global brand. He still defines himself as a geneticist, but it’s been decades since he was an active researcher or has even taught in a university setting. And his role as science’s interpreter was long ago supplanted by his calling as environmental evangelist.

Suzuki traces his own awakening back to The Silent Spring, Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking 1962 book. But his beliefs really came to the fore in the early ’80s, as he joined in the fight against clear-cut logging in what was then the Queen Charlotte Islands, now Haida Gwaii. “It was a totally unequal battle. The important things that forests do—like providing air—weren’t included in the economic equation.” In 1985, he produced an eight-part CBC special, A Planet for the Taking, criss-crossing the globe. That led to a high-profile part in the efforts to preserve the Amazonian rainforest, where he formed alliances with people like Anita Roddick, the founder of The Body Shop, and rocker-turned-activist Sting.

Suzuki soon became one of the green movement’s most visible champions. In 1991, he and a group of friends founded the David Suzuki Foundation, a non-profit that promotes environmental causes and education. In 1992, he spoke at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. That slow creep into the spotlight provided lots of ammunition for his critics. Around that time, the Globe and Mail dropped him as columnist, suggesting he had become too preachy, and then produced a scorching feature that painted him as a “media-wise politician” in a lab coat.

But those who know Suzuki well say there’s nothing manufactured about his concerns. David Schindler, a professor of ecology at the University of Alberta, recalls a canoe trip through the north of the province, where Suzuki ended up taking a plane ride with some First Nations chiefs to check out the oil sands. “He came back and he was incensed, just beside himself. He said, ‘We’ve got to stop this thing,’ ” says Schindler. “He gets very angry about the environment and social injustices.”

Suzuki says he used to think that his TV work was drawing attention to important issues, that the content was the star. Over the years, however, his view has changed. He’s been stopped too many times in the airport, or on the street, and complimented on a show he’s never done. He now realizes that for most viewers, he’s the constant—that rather than being the messenger, he’s the oracle.

“I’ve never made any pretense of being Mr. Know-it-all,” says Suzuki. But that doesn’t change public expectations that he should be able to pronounce on every issue, and debate all comers. When Suzuki doesn’t have an answer, or messes up his facts, as he did on Australian television, it’s news. Somewhere along the way, people started to assume he was infallible. “To the extent that I’ve failed, that’s it,” he says. “I’ve somehow got to be smarter.”

There was a time when it seemed like the war to protect the Earth was almost over.

Back in 1988, George H.W. Bush, a conservative Republican, campaigned on a pledge to become “the environmental president.” Suzuki remembers Lucien Bouchard, then the federal environment minister, and the biggest star in Brian Mulroney’s cabinet, earnestly telling him that global warming was “a threat to the survival of our species.” But all these years later, green crusaders find themselves refighting, or even losing, battles they thought were over long ago. Stories about atmospheric CO2 concentrations reaching the highest level in recorded history, or UN warnings of a looming worldwide famine due to global warming, receive far less attention than the latest development in the Senate scandal or Rob Ford video. In an Internet age, even Suzuki’s own reach has shrunk. CBC is happy to talk about how many awards The Nature of Things has won, but it won’t discuss its ratings, which now hold steady at about 400,000 viewers.

“Many of the battles that we fought 30 or 35 years ago, that we celebrated as enormous successes . . . Thirty-five years later, the same damn battles have started again. That’s where I think we failed,” Suzuki says. “We fundamentally failed to use those battles to get that awareness, to shift the paradigm. And that’s been the failure of environmentalism.”

Nearing the end of the journey, Suzuki finds himself standing before yet another mountain. It’s frustrating, but he says he isn’t ready to give up. Is he worried about his legacy? “When I’m dead, I won’t give a s–t what they say about me. I’ll be dead,” he snorts. “I’m not thinking about legacy. My concern now is to get the message out, to get people to understand how serious this is.”

Some of his compatriots believe it’s already too late to save our species. Suzuki is more optimistic. Nature, if given the chance, will be more forgiving than we deserve, he says. All humans have to do is start paying attention to the flashing warning signs.

At his Toronto trial, the verdict on David Suzuki came back “Not guilty.” The news didn’t make the next day’s papers.