With its patchwork of half-baked, absurd laws, Canada isn’t ready for legal weed

Canada is about to usher in the era of legal marijuana with laws and rules that contradict other ones elsewhere in the country—or even just across a bridge. Did it have to be like this?

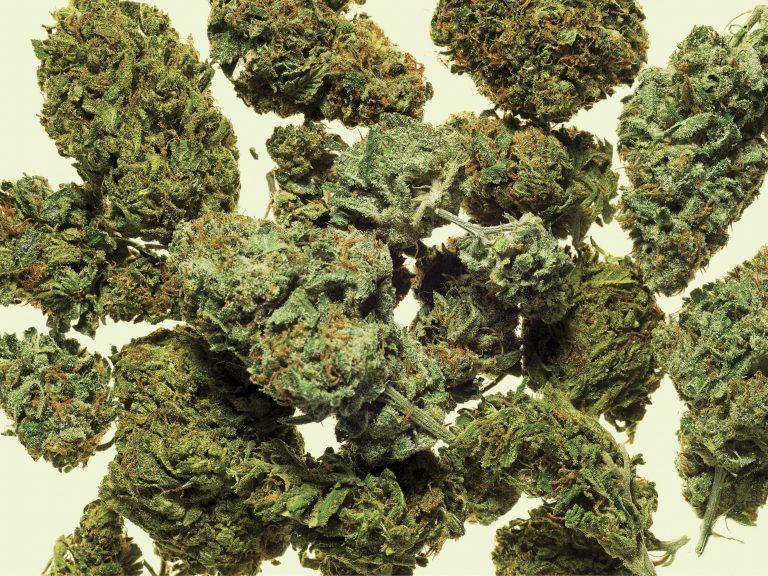

(Getty Images)

Share

Updated Sept. 27

Bobby Kennedy spent much of his time with lawyers and in court during the summer that was supposed to usher in Canada’s era of legal marijuana. In mid-July, the City of Kelowna had ordered him to shut down the display counter of his downtown skateboard shop, BKRY, where since winter he’d been dispensing weed gummies, brownies, dried cannabis and more. Kennedy fought to keep selling to his recreational and medicinal clients. But the B.C. Interior’s largest city was determined to push out all unregulated operators before cannabis is legalized nationwide on Oct. 17.

In Kelowna, as in much of the country, that much-anticipated day will fall far short of a new era dawning. The city, the epicentre of B.C.’s Okanagan wine region and the base for some large licensed cannabis growers, has barely begun approving rules, and is several months from being ready to pass businesses through its rezoning and permitting processes. It means Kelowna’s first legal pot stores will open not this fall but in the summer of 2019 at the earliest, says Ryan Smith, the city’s community planning manager. “The public expects us to put in place a model that is, to begin with, conservative,” he says.

The B.C. government, which has been late to the legalization game and only began taking private retail applications in August, will all but squelch Kennedy’s dream of running a hybrid shop selling skateboards and cannabis, and eventually establishing a chain of such “lifestyle cultivators.” Under provincial rules, a licensee can’t sell recreational pot as part of another business.

MARIJUANA FAQ: Everything about marijuana and its legalization, on a weed-to-know basis

It baffles Kennedy that in a province globally renowned for its bud, his own city is so unready to welcome the multibillion-dollar industry. Noting that elderly clients are unlikely to shop online for medicinal cannabis, he wonders whether “more guys are going to pop up illegally,” adding: “God speak the truth, I hope they do.”

For Kelownans, legally buying recreational pot on Oct. 17 will be an online-only affair, just as it will be in Ontario, where the new government’s late decision to allow private retail will delay the arrival of legal physical outlets until next April. Some provinces will have private shops ready to launch on day one, while others will boast government-run ones—20 in New Brunswick and the same number in vastly larger Quebec; a dozen in Nova Scotia and, at least to start with, a solitary public B.C. Cannabis Store in Kamloops (two hours’ drive from Kelowna, four from Vancouver).

With billions of dollars invested, millions of grams cultivated and thousands of people employed, the grand premiere of Canada’s legal cannabis system is almost upon us. From producers to front-line workers to police to many levels of regulators, a nation is scurrying to ready itself before the curtain lifts. But it will debut as a ragged production. Parts of the set may be unpainted. Not everyone will know their lines. The theatre may be variously oversold and partly empty. And whole sections of the stage will remain in darkness.

READ MORE: Trudeau is legalizing weed—but it hasn’t been pretty politically

That’s because Canada’s map will be worse than a splotchy patchwork of where one can shop for marijuana, where one can’t, where one can’t yet and where it kind-of-depends-on-a-few-things. Enforcement of drug-impaired driving laws and other new cannabis-related violations will vary from place to place. Home-grow rules will differ. You’ll be able to smoke a joint on the sidewalk in one city but not the next. In Halifax, you’ll need to seek out a designated toking zone. In Edmonton, find any part of the sidewalk that is not within 10 metres of a bus stop, patio, doorway or window.

“If you’re a person who moves around the country frequently, you’re literally going to need an app that tells you what’s legal and what’s not depending on where you are,” says Ottawa-based cannabis lawyer Trina Fraser. In March, she acquired a trademark for a yet-to-be-developed app, called Canna Do This? But she’s been so busy helping businesses navigate the new regulatory thicket that, come Oct. 17, the app won’t have gotten far past the idea stage.

By the time Parliament approved the Cannabis Act in June and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced the actual legalization day, most provinces were already developing public stores or vetting bids for private ones. But they did so only after going into a pace-of-government version of hyperdrive. “We were running at three times the speed we normally would for a project of this nature,” says David DiPersio, who leads the cannabis file for the Nova Scotia Liquor Corp.

Niaz Nejad of the Alberta Gaming and Liquor Commission (AGLC) is among a number of people interviewed for this article who likened the challenge to building an aircraft while flying it. In December, she added “and cannabis” to her job title of chief operating officer and vice-president of gaming. As such, she will soon become one of the legal pot world’s largest distributors, since all Alberta private retail stores must buy from the provincial wholesaler, which she oversees. Nejad has become so knowledgeable on marijuana strains and potencies that her friends joke she could sell on the corner, and she’s met the gamut of cannabis entrepreneurs. Some producers arrive to her boardroom table in businesslike groups of five or six; others come solo with eyes reddened or glazed, intimidated by the regulator’s seriousness. Rules of workplace decorum aren’t always in force. After a tense price negotiation, one industrial grower Nejad had been dealing with gave her a massive hug as though they’d known each other for decades. “The gaming suppliers don’t typically bearhug you after you’ve had a difficult negotiation,” she says with a laugh. “They may want to [put you in a] chokehold.”

READ MORE: All the green, leafy, pun-filled names of the pot stores coming to Alberta

Uncharted though its path is, Alberta is better equipped than most for private cannabis retail. It pioneered privatized liquor sales 25 years ago, and because it has had relatively few illegal cannabis dispensaries—swiftly cracking down on those that popped up—the province starts with a comparatively clean slate. There’s no cap, but the AGLC expects 250 cannabis stores to open in Alberta during the first wave, or 24 times more per capita than in Quebec. Calgary alone has approved permits for 117, more than Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia combined will initially allow.

But confusing Alberta’s coming pot-store proliferation with the Wild West would be like fearing that one toke makes you a squinting dope fiend. A tour of New Leaf Cannabis’s concept store in a west Calgary strip mall lays bare the tight regulations governing retailers. Windows are covered so nobody can see inside, like an adult video store. There are no large canisters of cannabis on display, only tiny sample smell jars cable-tethered to tables. In fact, all the product arrives at stores in federally mandated packages that look like a cross between cigarette packs and prescription medicine bottles: child-resistant and opaque, with small logos, much larger health warnings and a stop-sign-like red THC label. These unremarkable bud boxes and baggies must be stored in a backroom with steel-reinforced walls and doors. Conveniently, this concept store used to be a bank, so it’s all in a former vault, says chief administrative officer Angus Taylor. Staff will wander the Apple-style sales floor, swiping customers’ payment cards and retrieving purchased product from the locked backroom. But they’ll be banned from answering customers’ queries about pot’s potential medical benefits. All stores are solely for recreational-use marijuana.

Alberta municipalities have layered on their own unique permitting systems. Edmonton held a lottery to determine the order in which applications would be reviewed, and made a profoundly boring two-hour video of the process, which it uploaded to YouTube. Calgary was among the cities to offer first-come-first-serve applications. New Leaf had begun snapping up storefronts in mid-2017, before Alberta even announced the private retail model; to secure the company’s investment, Taylor camped out at City Hall the night before applications became available. Because the city won’t allow stores within 300 m of each other, there’s been a race for prime locations. Then, after council enacted a last-minute distance requirement between pot stores and payday lenders—lest, presumably, consumers blow their paycheques on weed—the permit for New Leaf’s concept store was refused. The company filed an appeal and won its permit, but solving the problem with the payday lender two doors down came at a cost. New Leaf simply bought out its neighbour’s lease.

READ MORE: Medical experts warn about marijuana’s alarming side—and how it can affect youth

Such confusion may have been inevitable, given that politicians and bureaucrats face the seemingly incompatible tasks of encouraging legal enjoyment of cannabis while simultaneously shielding everyone from its harms. They’ve been pulled in conflicting directions by entrepreneurs, law enforcement, health experts and grumpy seniors who vote, producing contradictions in rules from jurisdiction to jurisdiction that can border on the absurd. Calgary won’t allow pot shops to operate next to liquor stores (other municipalities have required a buffer zone of 100 m between them), while most Nova Scotia stores will be co-located inside provincial liquor outlets. While stores are not allowed to link products to medical advice, Maritime shops will tell customers how strains may make them feel: Nova Scotia stores will categorize varieties as relax, unwind, centre and enhance—while New Brunswick-sold pot will let users discover, connect or refresh. Stores in New Brunswick and Quebec will require ID checks upon entry; others won’t. Alberta’s online sales portal will require age-of-majority verification, while other province-run sales websites will have the simple checkbox method and request proof of age upon delivery. Manitoba and Saskatchewan will let its private brick-and-mortar retailers sell online, as well.

As the Alberta-based company Inner Spirit Holdings vies to build a national retail footprint, executives have found that it takes some hopscotch skills. The company hopes to open the maximum eight stores any chain is allowed in B.C., as well as the 37 allowed in Alberta; one of its franchise partners won a Saskatchewan lottery for a single store in Moose Jaw but nowhere else; and Inner Spirit will cater to Manitoba’s encouragement of Indigenous business participation by partnering in that province with the Dakota Tipi First Nation. “It’s complex and it doesn’t always make sense, but it’s just part of the entrepreneurial trail-blazing—you roll with the punches,” says CEO Darren Bondar.

READ MORE: If you’ve ever smoked marijuana, beware of the U.S. border

His chain has applied in the pot-friendly Alberta mountain town of Canmore, which stands to have eight stores for its 14,000 residents. Perhaps too much of a good thing, says the managing partner of a Starbuds franchise on its Main Street. “If you quit your full-time job to do this and then seven other of the same shops open up in your small town, you’d be pretty worried too,” says co-owner Brad Murphy, a former utilities worker. In neighbouring Banff, council hadn’t finalized rules by September, so it likely won’t have any retailers ready to open by Oct. 17. What’s more, the town’s proposed rules ban any cannabis outlets with storefronts that face onto sidewalks, suggesting Banff will have something less than the “Alpine high” atmosphere that characterized the resort town of Aspen after Colorado legalized recreational pot. But it’s still more permissive than the resort town of Whistler, B.C., which will initially ban stores, as will North Vancouver, West Vancouver and Richmond (though, paradoxically, the latter will host the province’s centralized cannabis distribution warehouse).

Indeed, despite the reputation of B.C. bud, the province lags behind Nova Scotia and Alberta in per-person marijuana consumption. And call it laid-back or go-slow, but B.C. was the last province to start considering private retail applications—in August, with 10 weeks to go until legalization day. The justice ministry wouldn’t say whether approvals will be ready in time, noting much will depend on municipalities. Kelowna, Abbotsford and Burnaby were among those still figuring out their approaches with less than two months to go.

In Vancouver, most safe bets are that Oct. 17 will look much like all the days before it. The city, which at one point had more unregulated dispensaries than Starbucks coffeehouses, brought in its own civic licensing regime in 2015, before the passage of federal or provincial rules; 19 are licensed, but far more have only partial okay or fall outside regulations. And a business licence doesn’t automatically mean a store will be okay under the new province-led regime: the B.C. government asks a city for its assessment of provincial licence applicants. But in late August, chief licence inspector Kathryn Holm said Vancouver was still sorting out how to choose its winners and losers. There will be added twists, as what the city previously regulated as “medical marijuana-related” businesses transition to the federal government’s recreational-only model. Stores with terms like “medicinal,” “dispensary” and “health” in their names will have to rebrand. Among other requirements, Vancouver had barred its licensees from having any window coverings, to make it harder to conceal illicit activity. But provincial rules now encourage fully covered windows by requiring that no product displays be visible from outside a store.

Jamie Shaw, a Vancouver cannabis consultant, ventures that some long-established stores in the city—or “clubs,” as they were known—will fight to maintain their status as quasi-medical suppliers, because they’ve never considered themselves recreational. Others, she says, “will refuse to comply because it’s easiest for them not to at first.” But many existing retailers are willing to sacrifice for the legal shift, Shaw says, even if that means a massive overhaul that includes having to jettison edibles and buy only from the provincial distributor. For legalization, the B.C. government is assembling a unit of specialized officers to perform unwarranted entry and seizures in illegal stores. But dispensary owners are hoping the NDP government stays true to its plans to start out lenient. “Unlicensed retailers won’t be shut down overnight,” Solicitor General Mike Farnworth said in June.

In Ontario, the Doug Ford government appears keen to take the opposite approach during the nearly half-year wait between Oct. 17 and when Ontario will have its private retail regime in place. When he announced in mid-August that the province would switch from the previous Liberal government’s public-only model to a private system coming in April, Finance Minister Vic Fedeli noted much of the system design would be guided by public, business and municipal consultation. In the meantime, he threatened “zero tolerance” for existing unregulated dispensaries and “severe and escalating fines for any infractions.”

That brings comfort to officials in Hamilton, which hosts a disproportionate 53 dispensaries and has worked with local law enforcement to try shutting illegal players down—“but the next day they would be open again, fully stocked and ready to go,” says city licensing director Ken Leendertse. It’s been like whack-a-mole in Toronto, too, with many former store operators going online-only, says Toronto industry veteran Abi Roach (not her given name), owner of the long-standing Hotbox lounge and bong shop. As major retailers from elsewhere now eye Toronto, current operators there are expected to either seize the opportunity to go legit or go underground. Roach, for one, held off selling product, sticking to equipment and paraphernalia. But now she wants in. “I’ve waited 18 years and was a good little girl and didn’t break the law for a very long time. I’ve been waiting for this date and hoped it would come.”

A six-month wait beyond legalization may seem short to Roach. So will it, likely, to the province and municipal councils as they race to plan and implement what other jurisdictions felt rushed to pull off in a year or more. (The province’s state of disorganization is even more striking when viewed against the backdrop of history: on June 1, 1927, the day a much smaller Ontario ended alcohol Prohibition, it opened 16 stores and three mail-order departments.) “Changing gears at this point? I’m sure as hell happy we’re not doing it [in Alberta],” says Alain Maisonneuve, head of the AGLC. Adds Fraser, the Ottawa cannabis lawyer: “It’s just crazy to think all that’s going to happen that quickly.”

Joël Dubois puzzles over another aspect of Canada’s legalization as he designs a law school course on cannabis for this coming year at the University of Ottawa. Many Ottawans take lunch-break walks across the Ottawa River into Gatineau, Que. Quebec is treating cannabis like tobacco, so users can light up in the streets; Ontario, however, will treat it like liquor, which can’t be consumed in any public outdoor place. “Theoretically, at some point on that interprovincial bridge, you’ll be able to light up, smoke while you’re walking on the Gatineau side, and have to butt out on the way back,” he says. [UPDATE: Three weeks before Oct. 17 legalization, Ontario announced it would pass legislation that allows cannabis consumption in outdoor public places, as will be the case in Quebec.]

Other provinces like Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador are also banning public consumption, while it’s a city-by-city decision in Alberta. Calgary, which will ban outdoor use but is alive to the fact some apartment and condo buildings ban all forms of smoking, has proposed the designation of four green spaces around the city as legal weed-smoking zones. City lawyers in Halifax, meanwhile, convinced council that it’s so hard for enforcement officers to definitively tell pot from tobacco that it should just ban smoking on sidewalks and streets altogether. Councillor Sam Austin voted in favour, but faced widespread cries of overreach and has since asked colleagues to reconsider. Council is now eyeing a series of signed tobacco-or-weed-smoking areas. But even that may not keep the peace, says Austin. “It’s going to be no end of little street-by-street battles about where the smoking zone’s going to be; with some bars upset and they want it closer to them, one condo’s owners worrying about walking past where everybody’s on the street puffing.”

Federal law permitting Canadians to grow four plants per household have resulted in similar hindrances and contradictions. Manitoba and Quebec will prohibit home growing altogether, while British Columbia will okay it as long as it’s not visible through a window or a fence. And parents accustomed to running liquor-store errands with a toddler in tow are about to run up against Ottawa’s apparent determination to shield children from ever witnessing anything pot-related. Across the country, minors are banned from entering cannabis stores—a proscription that will be felt keenly by those using Nova Scotia’s liquor-cannabis hybrid stores; the retailers will provide no babysitting service if a parent wants to quickly hop over to the marijuana side.

Not that the shopping experience will resemble anything like a quick hop. Nova Scotia’s “what to expect” marketing campaign warns of long lineups at the province’s dozen outlets; officials expect each transaction to take 15 to 20 minutes because there’s no self-service, and many users will need lots of information about the product options and varieties. “Basic things they know about alcohol they would not know about cannabis,” says the province’s DiPersio.

READ MORE: What Canada’s plan to regulate legal weed gets wrong

A nation of law enforcement officers will also have to quickly get up to speed on the new age that begins in October. A standardized two-hour course on the federal Cannabis Act finally came out in mid-August, requiring police services around the country to carve a quarter-day out of the schedule for every front-line officer to train on the new legislation, on top of training for provincial and local rules. That doesn’t include the new impaired-driving laws, which will expose how unready many of Canada’s police divisions are to crack down on stoned motorists. In the B.C. Lower Mainland, Delta Police Chief Neil Dubord says that by year’s end, nine of his 200 officers will be trained as drug recognition experts (DREs), able to verify drug-impaired driving charges. That’s still better than the one DRE Delta had two years ago, and compares well to the nine recognition experts currently in the 1,327-member Vancouver Police Department. These in-house experts will have to carry the freight in the early days post-legalization, since the first roadside saliva-testing device for THC (marijuana’s intoxicating agent) was only approved by Justice Canada in late August; procurement and officer training will take time. At $5,000 per toaster-sized machine, Dubord doesn’t expect his department will get many, and probably none before next spring. But he’s not worried about a sudden spike in demand for enforcement come mid-October: “I don’t think there’s going to be this wash of people buying an ounce and getting high,” he says.

READ MORE: Are Canada’s police forces prepared for stoned drivers?

Finally, while almost everybody is expecting a complicated and bumpy first few months after legalization, the icing on the cake could literally be icing and cake. By October 2019, Ottawa must have new regulations in place for cannabis edibles, which for now remain banned. Regulators will soon launch consultations about product types, marketing and food-handling issues; stores that launch in the first year will save room to add fridges and shelves. “This is big now—when edibles come, it’s going to be about 10 times the size of dried flowers and oils,” said Alberta’s Nejad.

If the history of alcohol is any guide, it’s reasonable to think conservative regulations and bans will eventually be loosened. Cannabis lounges could eventually be sanctioned. Alternatively, there could be counter-revolutionary moves—Quebec’s opposition leader, François Legault, has pledged that if he wins the fall election, he will boost the cannabis age to 21 from 18. But there will be time, down the road, to ponder future changes. For most Canadians, the ones under way are proving brain-numbing enough.