Shared around the world: On satire, words, and freedom of the press

Quotes and ideas on satire and free press in the aftermath of the Paris attacks on Charlie Hebdo

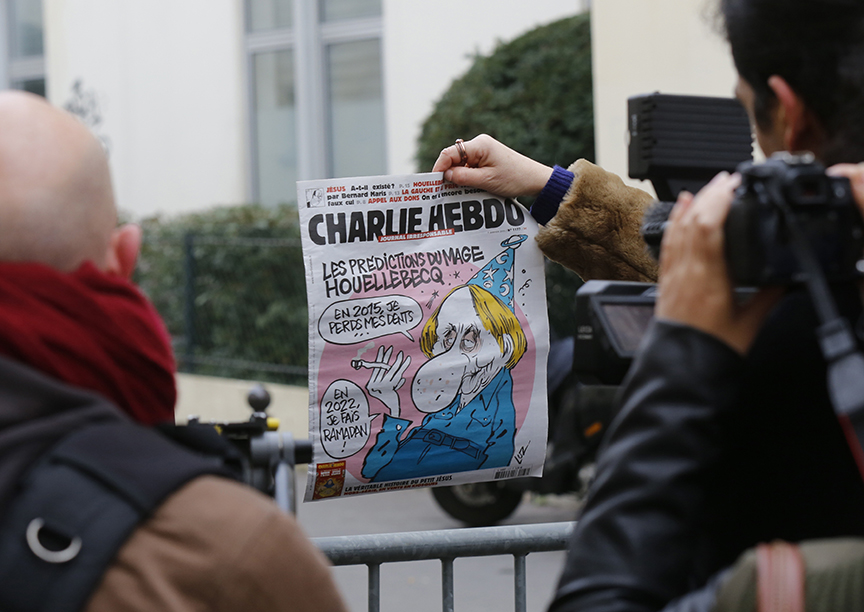

A man holds up the front page of the latest issue of Charlie Hebdo, a satirical magazine, which shows a caricature of French author Michel Houellebecq. At least 12 have died in a shooting at the Charlie Hebdo offices. (Jacky Naegelen/Reuters)

Share

Along with expressions of confusion, dismay and outrage about the tragedy in Paris, social media users pointed to similar moments in history, sharing quotes and speeches about the importance of ruthless satire, criticism and freedom of the press.

Related reading:

Brian Bethune on satire’s long, courageous tradition

How Facebook may start the defanging of satire

Here’s a roundup of those that stood out, with a few relevant additions:

1. Rowan Atkinson, who urged the U.K. government in 2006 to back down over its religious hatred bill and instead, bolster the right of performers to criticize religion.

“It is absolutely right and reasonable that religions should be protected from threatening language, behaviour and written material but I support the amendment to retain the right to abuse and insult, because of the essentially irrational nature of religious beliefs. That is not to dismiss them: indeed, I’m a great believer that the most important and most sustaining things in life are essentially irrational. Love, beauty, art, friendship, music, spirituality of whatever form, these things make no rational sense yet they are more important than any qualities that are rationally measurable. Those who think that, as they lie on their deathbed, they will be able to judge the success of their lives by how big a BMW they could afford at the end of it, are in for a big surprise. However, it’s their irrational nature that leaves religious beliefs wide open to interpretation, allowing occasionally practices to be established that are wholly contrary to the mores of a civilised, liberal society.”

2. Christopher Hitchens, from his February 2006 article, The case for mocking religion, which responded to the outrage over the printing of Charlie Hebdo‘s Mohammed cartoons in Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten.

“The innate human revulsion against desecration is much older than any monotheism: Its most powerful expression is in the Antigone of Sophocles. It belongs to civilization. I am not asking for the right to slaughter a pig in a synagogue or mosque or to relieve myself on a “holy” book. But I will not be told I can’t eat pork, and I will not respect those who burn books on a regular basis. I, too, have strong convictions and beliefs and value the Enlightenment above any priesthood or any sacred fetish-object. It is revolting to me to breathe the same air as wafts from the exhalations of the madrasahs, or the reeking fumes of the suicide-murderers, or the sermons of Billy Graham and Joseph Ratzinger. But these same principles of mine also prevent me from wreaking random violence on the nearest church, or kidnapping a Muslim at random and holding him hostage, or violating diplomatic immunity by attacking the embassy or the envoys of even the most despotic Islamic state, or making a moronic spectacle of myself threatening blood and fire to faraway individuals who may have hurt my feelings.”

3. On Yom Kippur in 2012, New Yorker cartoon editor Robert Mankoff curated a cheeky array of cartoons rife with blasphemy and religious stereotypes. “Through modern eyes this, too, is vaguely offensive, and, when I get some time, believe me, I plan to be vaguely offended by it,” he wrote. In one cartoon, a man shakes a priest’s hand on his way out from church and says, “Oh, I know He works in mysterious ways, but if I worked that mysteriously I’d get fired.”

And the final cartoon, a blank box, with this caption: “Please enjoy this culturally, ethnically, religiously and politically correct cartoon responsibly. Thank you.”

4. Jonathan Swift from the opening to his 1704 The Battle of the Books .

“Satire is a sort of glass wherein beholders do generally discover everybody’s face but their own; which is the chief reason for that kind reception it meets with in the world, and that so very few are offended with it. But, if it should happen otherwise, the danger is not great; and I have learned from long experience never to apprehend mischief from those understandings I have been able to provoke: for anger and fury, though they add strength to the sinews of the body, yet are found to relax those of the mind, and to render all its efforts feeble and impotent. …. Wit without knowledge being a sort of cream, which gathers in a night to the top, and by a skilful hand may be soon whipped into froth; but once scummed away, what appears underneath will be fit for nothing but to be thrown to the hogs.”

5. Winston Churchill, in a speech he gave in 1949, when the British Royal Commission on the Press ruled that newspapers would not be improved by state intervention.

“A free press is the unsleeping guardian of every other right that free men prize; it is the most dangerous foe of tyranny … Under dictatorship the press is bound to languish, and the loudspeaker and the film to become more important. But where free institutions are indigenous to the soil and men have the habit of liberty, the press will continue to be the Fourth Estate, the vigilant guardian of the rights of the ordinary citizen.”

6. Comedian Bill Hicks, in a letter he wrote to a priest who complained about his recent act on Channel 4.

“You say you found my material ‘offensive’ and ‘blasphemous.’ I find it interesting that you feel your beliefs are denigrated or threatened when I’d be willing to bet you’ve never received a single letter complaining about your beliefs, or asking why they are allowed to be. (If you have received such a letter, it definitely did not come from me.) Furthermore, I imagine a quick perusal of an average week of television programming would reveal many more shows of a religious nature, than one of my shows — which are called ‘specials’ by virtue of the fact that they are very rarely on … In support of your position of outrage, you posit the hypothetical scenario regarding the possibly ‘angry’ reaction of Muslims to material they might find similarly offensive. Here is my question to you: Are you tacitly condoning the violent terrorism of a handful of thugs to whom the idea of ‘freedom of speech’ and tolerance is perhaps as foreign as Christ’s message itself? If you are somehow implying that their intolerance to contrary beliefs is justifiable, admirable, or perhaps even preferable to one of acceptance and forgiveness, then I wonder what your true beliefs really are…

I hope I helped answer some of your questions. Also, I hope you consider this an invitation to keep open the lines of communication. Please feel free to contact me personally with comments, thoughts, or questions, if you so choose. If not, I invite you to enjoy my two upcoming specials entitled ‘Mohammed the TWIT’ and ‘Buddha, you fat PIG’. (JOKE)”

7. Voltaire, in a 1733 letter to a high-ranking government official during extreme censorship in France.

“As you have it in your power, sir, to do some service to letters, I implore you not to clip the wings of our writers so closely, nor to turn into barn-door fowls those who, allowed a start, might become eagles; reasonable liberty permits the mind to soar — slavery makes it creep.

Had there been a literary censorship in Rome, we should have had today neither Horace, Juvenal, nor the philosophical works of Cicero. If Milton, Dryden, Pope, and Locke had not been free, England would have had neither poets nor philosophers; there is something positively Turkish in proscribing printing; and hampering it is proscription. Be content with severely repressing diffamatory libels, for they are crimes: but so long as those infamous calottes are boldly published, and so many other unworthy and despicable productions, at least allow Bayle to circulate in France, and do not put him, who has been so great an honour to his country, among its contraband.”

8. George Orwell, in his essay “The Freedom of the Press,” which he hoped would preface Animal Farm in 1945, but wasn’t published until 1972.

“I mentioned the reaction I had had from an important official in the Ministry of Information with regard to Animal Farm. I must confess that this expression of opinion has given me seriously to think … I can see now that it might be regarded as something which it was highly ill-advised to publish at the present time. If the fable were addressed generally to dictators and dictatorships at large then publication would be all right, but the fable does follow, as I see now, so completely the progress of the Russian Soviets and their two dictators, that it can apply only to Russia, to the exclusion of the other dictatorships. Another thing: it would be less offensive if the predominant caste in the fable were not pigs. I think the choice of pigs as the ruling caste will no doubt give offence to many people, and particularly to anyone who is a bit touchy, as undoubtedly the Russians are…

The chief danger to freedom of thought and speech at this moment is not the direct interference of … any official body. If publishers and editors exert themselves to keep certain topics out of print, it is not because they are frightened of prosecution but because they are frightened of public opinion. In this country intellectual cowardice is the worst enemy a writer or journalist has to face. … The sinister fact about literary censorship in England is that it is largely voluntary.”

9. Mark Twain, in License of the Press, 1873.

“It has become a sarcastic proverb that a thing must be true if you saw it in a newspaper. That is the opinion intelligent people have of that lying vehicle in a nutshell. But the trouble is that the stupid people—who constitute the grand overwhelming majority of this and all other nations—do believe and are moulded and convinced by what they get out of a newspaper, and there is where the harm lies.

Among us, the newspaper is a tremendous power. It can make or mar any man’s reputation. It has perfect freedom to call the best man in the land a fraud and a thief, and he is destroyed beyond help.”

10. A 1917 poem by Rudyard Kipling.

Why don’t you write a play —

Why don’t you cut your hair?

Do you trim your toe-nails round

Or do you trim them square?

Tell it to the papers,

Tell it every day.

But, en passant, may I ask

Why don’t you write a play?What’s your last religion?

Have you got a creed?

Do you dress in Jaeger-wool

Sackcloth, silk or tweed?

Name the books that helped you

On the path you’ve trod.

Do you use a little g

When you write of God?Do you hope to enter

Fame’s immortal dome?

Do you put the washing out

Or have it done at home?

Have you any morals?

Does your genius burn?

Was you wife a what’s its name?

How much did she earn?Had your friend a secret

Sorrow, shame or vice –

Have you promised not to tell

What’s your lowest price?

All the housemaid fancied

All the butler guessed

Tell it to the public press

And we will do the rest.Why don’t you write a play?