The Internet hates Section 13

Either Section 13 of the Human Rights Act had to go, or the Internet did.

Share

There are many reasons to be glad Section 13 of our Human Rights Act is all but dead. For one, we already have hate speech laws, if you’re into that sort of thing. Section 319 of The Criminal Code of Canada bans the “wilful promotion of hatred” toward “an identifiable group.” It’s weird to me that the promotion of an emotion is against the law, but I get what the law is going for, and at least it’s enforced like any other law—by the police, selectively. If the identifiable group you promote hatred toward is Nickelback, the cops will probably leave you alone.

Human Rights Code violations on the other hand are investigated by the Code’s own little bureaucracy, the Human Rights Commission, and offences are judged by their own kangaroo court, the Human Rights Tribunal. Cases arise whenever a citizen makes a claim. If you make a successful hate speech claim, you can be awarded money in fines collected from the guilty party, even if you weren’t the target of their hate speech. And there’s nothing to stop an employee of the Human Rights Commission itself, say a lawyer who knows exactly how the process works, from making a claim.

We know this because that’s what happened. A former employee of the commission launched the vast majority of Section 13 cases during the past 12 years, winning all but one of them and collecting thousands of dollars. His name is Richard Warman, and you might call Section 13 “Richard’s Law.”

As I said, there are lots of reasons to applaud the scrapping of this ridiculous bit of legislation. But there’s one reason in particular that has me celebrating its pending demise: Section 13 was an anti-Internet law. Seriously, either it had to go, or the Internet did.

Richard Warman’s final Section 13 complaint was against “white nationalist” Marc Lemire, who hosts the Freedom Site web forum, where fellow “white nationalists” hang out and discuss “white supremacy nationalism.” But it wasn’t Lemire’s speech that Warman found hateful. It was Craig Harrison, a contributor to Freedom Site, who allegedly violated our hate speech laws by allegedly subjecting a group to hate. But Lemire ran the site, so he was the one Warman targeted. And by the vague, anachronistic language of Section 13, he was the right target.

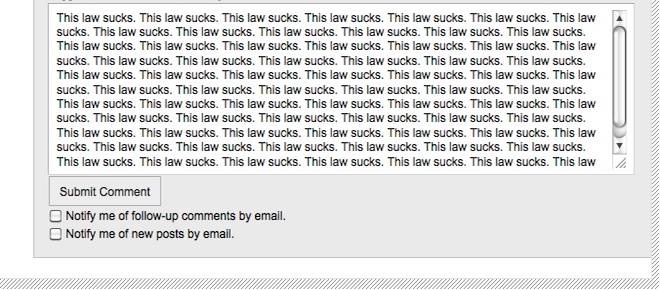

That’s why Section 13 hates the Internet: it makes no distinction between the publisher of a comment and the publisher of a website. If Section 13 were to remain a law, and one that’s actually enforced by Canadians other than Richard Warman, then you simply couldn’t host any kind of interactive website. Youtube would go, Wikipedia would go, Macleans.ca and every other site with a comment section would go. It gets sillier the more you think about it. Warman has admitted to posing as a white supremacist and joining Freedom Site to help his “investigations.” If Section 13 were to stand, and website publishers were held liable for what their users post, then someone could theoretically join a site, leave hateful messages, file a complaint against the site’s owner, and then collect a cash prize, profiting from their own hate speech.

The Human Rights Commission came to their senses in 2009 when Warman’s complaint against Lemire reached their tribunal. Rather than rule that Lemire violated Section 13, tribunal member Athanasios Hadjis ruled that Section 13 violated our Charter, setting into motion a process that led directly to last week’s private member’s bill repealing the law itself. It’ll be off the books in a year, and not a moment too soon.

Jesse Brown is the host of TVO.org’s Search Engine podcast. He is on Twitter @jessebrown