What ‘Going Clear’ means for the decline of Scientology

HBO’s documentary about Scientology finally crosses the border into Canada. What does it say about the Church’s future?

Pedestrians walk past the Church of Scientology Celebrity Centre International, where police are conducting a crime scene investigation Sunday, Nov. 23, 2008, in the Hollywood section of Los Angeles. A security guard shot and killed a man wielding a sword Sunday on the grounds of this Scientology building, police said. (AP Photo/Ric Francis)

Share

Listen to The Thrill, Maclean’s weekly pop-culture podcast, take on ‘Going Clear’. Subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher or Beyondpod, and check out our other audio offerings:

Nan McLean first joined the Church of Scientology in Toronto in 1969 when she was 46 years old. She was out driving and heard reporters on the radio discussing the religion she had never heard of. When one reporter mentioned that Scientologists believe in reincarnation, she got so excited she almost drove off the road. “I always believed in reincarnation, but wasn’t sure how I could practise it—until then,” she recalls. A few weeks later, McLean, her husband, and two sons made it official. She walked into the Church—at that time a house on Avenue Road before it moved to its Yonge Street location–and paid $500 for the first required course, excited to start this new chapter in her life. “I still remember that was the weekend Armstrong walked on the moon,” she says. “It felt good to be part of a community, something different.”

But after a year and a half of what she calls hypocrisy, and allegations of physical and mental abuse, the McLean family decided they wanted out. For 18 months before they left, her son John had been part of the Sea Org (short for Sea Organization)—an elite contingent of devout Scientologists who sign a billion-year contract dedicating their life to working for the church—working aboard the Apollo, the yacht that served as founder L. Ron Hubbard’s headquarters. John convinced Sea Org to let him go, and he joined his family back home. Since then, McLean has devoted her life to helping other Scientologists who want to leave, and stays in touch with former members across the country. “I know first-hand that members of this group are controlled by fear, that’s why people stay in it even when things are horrible,” she says.

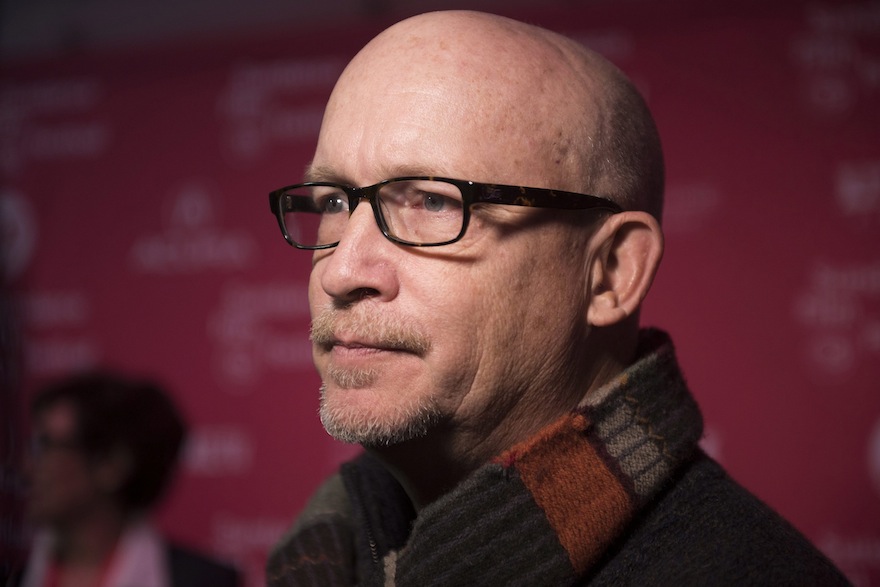

Now 91, and still living in Toronto, McLean believes strongly that Scientology should cease to exist, but says that will take time—and public outcry. That’s why she has been anxiously following press coverage of Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief, the new HBO documentary based on Lawrence Wright’s 2013 investigative book (it had its U.S. premiere in March but is only now being released in Canada in select theatres and on iTunes). The term “clear” is found in Hubbard’s 1950 bestselling book, and foundational Scientology text, Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health, referring to a state of mind Scientologists can achieve through study and practice. “My goal wasn’t to write an exposé,” Wright tells director Alex Gibney in an interview in the film. “It was simply to understand Scientology.” Ultimately, his book and the film serve both goals.

Gibney (known for his films that take on religion’s dark side) weaves details of Scientology’s complex, and often contradictory, history with interviews with eight ex-Scientologists, including people who made it to the church’s upper echelons, such as

Paul Haggis, the Academy Award-winning filmmaker from London, Ont., who in 2009—after 35 years in the church—left Scientology because of its support for an anti-gay-marriage ballot initiative in California.

Spanky Taylor, a woman who was a Scientologist for 17 years, and was assigned to work with John Travolta after he first joined in 1975, says in the film that she was sent to the church’s “Rehabilitation Project Force,” what she described as a prison camp on the seventh floor of the Scientology headquarters for members of the Sea Org who criticized the church, after she confronted the church for not providing adequate medical treatment for her boss. She describes brutal living and working conditions—30 hours on, three hours off with little food—and how she was forced to hand her daughter over to other members so that motherhood wouldn’t compromise her devotion. She wonders why Travolta, her close friend at the time, didn’t help her get out sooner even though she says he knew about the abuses she faced. “I often wonder what could possibly keep him there,” she says.

Much of the film focuses on the auditing sessions—a cornerstone of Scientology—that Scientologists participate in as part of their spiritual journey. An auditor listens as the person being audited divulges their feelings and life experiences. The auditor takes meticulous notes while the whole thing is recorded. According to former members quoted in the film, Travolta’s auditing sessions were secretly recorded, even though he requested they not be. In an interview, Wright describes how a Scientologist was tasked with compiling a “black PR folder” that allegedly contained every salacious detail from Travolta’s sessions to use against him should he decide to leave.

McLean was disappointed when she couldn’t find Going Clear online or on TV—the documentary has yet to air on HBO Canada—but she hopes it might signal the final stages of the church’s demise. “Each moment like this is a new step in the right direction,” she says.

The Church of Scientology has withstood countless allegations of abuse, corruption and fraud ever since it was founded in 1954 by 43-year-old L. Ron Hubbard, a sci-fi writer from Nebraska. A brief timeline of its history paints a picture of the young religion’s resiliency:

During the 1970s and 1980s, Scientologists infiltrated government agencies in the U.S. and Canada and stole hundreds of documents as part of Operation Snow White, the church’s mission to get a hold of any potentially damning documents about them and Hubbard; 11 Scientologists were convicted of conspiracy in 1980. But the church recovered from the scandal quickly, still managing to convert an impressive roster of celebs, including Travolta, Kirstie Alley and Tom Cruise, who joined in 1990.

It was shortly after that, with the rise of the Internet, that many ex-Scientologists took to chat rooms and forums to document their stories of alleged exploitation and to protest the church’s rigid hierarchy. Since then, the church has tried every trick in the book to combat the deluge of negative posts. In 2009, it became the first group officially banned from Wikipedia after creating numerous accounts dedicated to deleting anything disparaging. The church has also been in a heated battle with hacktivist group Anonymous, which has targeted it since 2008 after the church tried to remove a video of Tom Cruise that Anonymous posted to YouTube. In Germany, government ministers have been trying to ban Scientology, as critics there deem it a cult. And in 2009, a French court convicted the church of fraud and slapped it with an $800,000 fine.

Then there are the scathing films and tell-all books: the 2010 Australian documentary Scientology: The Ex-Files follows ex-members of the church’s Sea Org as they describe what they claim were slave-like living conditions, forced abortions and torture (a 2010 FBI investigation into Sea Org yielded no charges). And in 2013, ex-Scientologist Jenna Miscavige Hill, niece of the leader of the Church of Scientology David Miscavige, published her memoir, Beyond Belief: My Secret Life Inside Scientology and My Harrowing Escape, where she delves into stories of brainwashing and child labour while she was part of the church.

For Stephen Kent, a professor at the University of Alberta who specializes in Scientology and new religious movements, the revelations in Going Clear might not be entirely new, especially since it’s based on a two-year-old book, but will likely contribute to preventing prospective members from joining. And Wright and Gibney’s combined credentials give new weight to claims that have been circulating for decades.

“For years, people have been predicting the demise of Scientology,” Kent tells Maclean’s. “That hasn’t happened. But we do know it’s under siege and on the decline. Most new religions don’t make it beyond a few generations, and Scientology is definitely in that cycle.”

Religions emerge in relation to and reaction against historical and cultural circumstances, and when those change, as they already have, the religion becomes less relevant and will have diminished appeal, says Kent. “In order to be successful, a religion has to successfully cultivate its children.” Kent claims that Scientology, especially at the upper levels, is quite harsh on children; it has been reported that, since 1987, members of Sea Org are prohibited from having kids.

When Kent first arrived in Edmonton in 1984, the Church of Scientology had a large, high-profile office downtown, but now operates in a tiny office outside of the city. A 2012 Maclean’s e-book on Scientology describes Scientology’s relationship with Canada. In 2011, the Church announced plans to set up one of its few retreats—and new Sea Org base—at a golf resort in Mono, Ont., near Orangeville. But with only seven churches and an estimated 2,500 members in Canada, Scientology isn’t exactly thriving here. Even though it claims to be the world’s fastest-growing religion, the American Religious Identification Survey reported 25,000 Scientologists in the U.S., down from 45,000 in 1990.

Further, Kent says the film could change the ways academics study Scientology, particularly when it comes to using testimony from former members, which he says academia is often quick to dismiss. “There has been a very odd but persistent reaction against using the accounts of former members of Scientology in academic work,” he says. “They can be seen as disgruntled former members. And I’ve used accounts of former members and have had others attempt to discredit me. Of course [the former members] could be lying, but it’s up to experts [academics] to corroborate what they say.” Kent hopes Going Clear might encourage academics to take these various perspectives more seriously.

Kent tells Maclean’s he believes the biggest misconception about Scientology is that it’s even a religion at all. “I define it as a multi-national conglomerate, only one part of which is religious,” says Kent. But he doesn’t go so far as to call it a cult. “I’m more concerned about groups that cause harm regardless of what sort of label we put on them. And that’s the sort of thing Going Clear is about.”