Shakespeare is owed an apology

Colby Cosh on why Shakespeare’s critics will never be satisfied

Share

Maclean’s has, in more than a century of life, occasionally covered the various species of controversy over Shakespeare’s identity. Now, me, I take the radical minority position that the author William Shakespeare was also the historical person from Stratford-upon-Avon who appears in a few legal documents as “William Shakespeare.” But alternative theories number in the dozens. “Shakespeare” was really the earl of Oxford; Francis Bacon; Christopher Marlowe.

Someone is always trying to argue, generally by the use of abstruse textual hints or even anagrams, that Shakespeare was secretly a Catholic or a spy or a woman—anything, really, other than a backwater bourgeois with a decent education, a large ambition, and a remarkable imagination. It was at about Shakespeare’s time when cynical, hustling, free-thinking “creatives” began to invade the big cities of the English-speaking world, and they are still doing it. The Bard should not really be so hard to recognize.

At times, the moves in the revisionists’ identity game are so ludicrous, they become good arguments that Shakespeare is Shakespeare, showing how far you have to reach to imagine otherwise. “Shakespeare” had to have been a lawyer, say the amateur scholars, because the court scene in The Merchant of Venice is so true-to-life—totally something that could actually happen! “Shakespeare” couldn’t have written the “procreation” sonnets as a young man, because their narrator complains of advancing age, and we all know people don’t start doing that in their 30s! “Shakespeare” must have travelled widely on ships, because people use them in his plays, mostly eschewing hovercrafts and bullet trains!

By an amusing irony, the English King Richard III, whose popular image was created by Shakespeare, is another historical figure who has prejudices projected onto him more often than he is just looked at soberly. Richard always had a bit of a cult—certainly in the north of England, which never regained the huge helping of political power he gave it, and among people who have objections or beefs with the house of Tudor that ousted him, notably Roman Catholics.

In 1951, when the author Josephine Tey published The Daughter of Time, these happy few were joined by a mass wave of people who simply love conspiracies and historical secrets—the sort who adore getting the long-suppressed real poop, which, in this case, is that Richard III was a benign, gentle soul, and not the malformed usurper of legend. Tey had, apparently, studied his face—i.e., a painting of it—and concluded that no one who glowed with such sweet thoughtfulness could be a vicious killer.

Needless to say, because Richard was actually the Darwinian distillation of several generations of mafioso homicide, this required a big pile of omissions and absurdities. The planet-sized one is those princes in the Tower, Edward V and his brother Richard, who were entrusted to Richard’s care. Richard declared them illegitimate by a shabby contrivance, and they disappeared without notice or investigation while Richard was still in power, power he had consolidated with a sequence of open legal murders. But we are asked to believe without evidence that it was Henry VII who ordered the princes’ deaths.

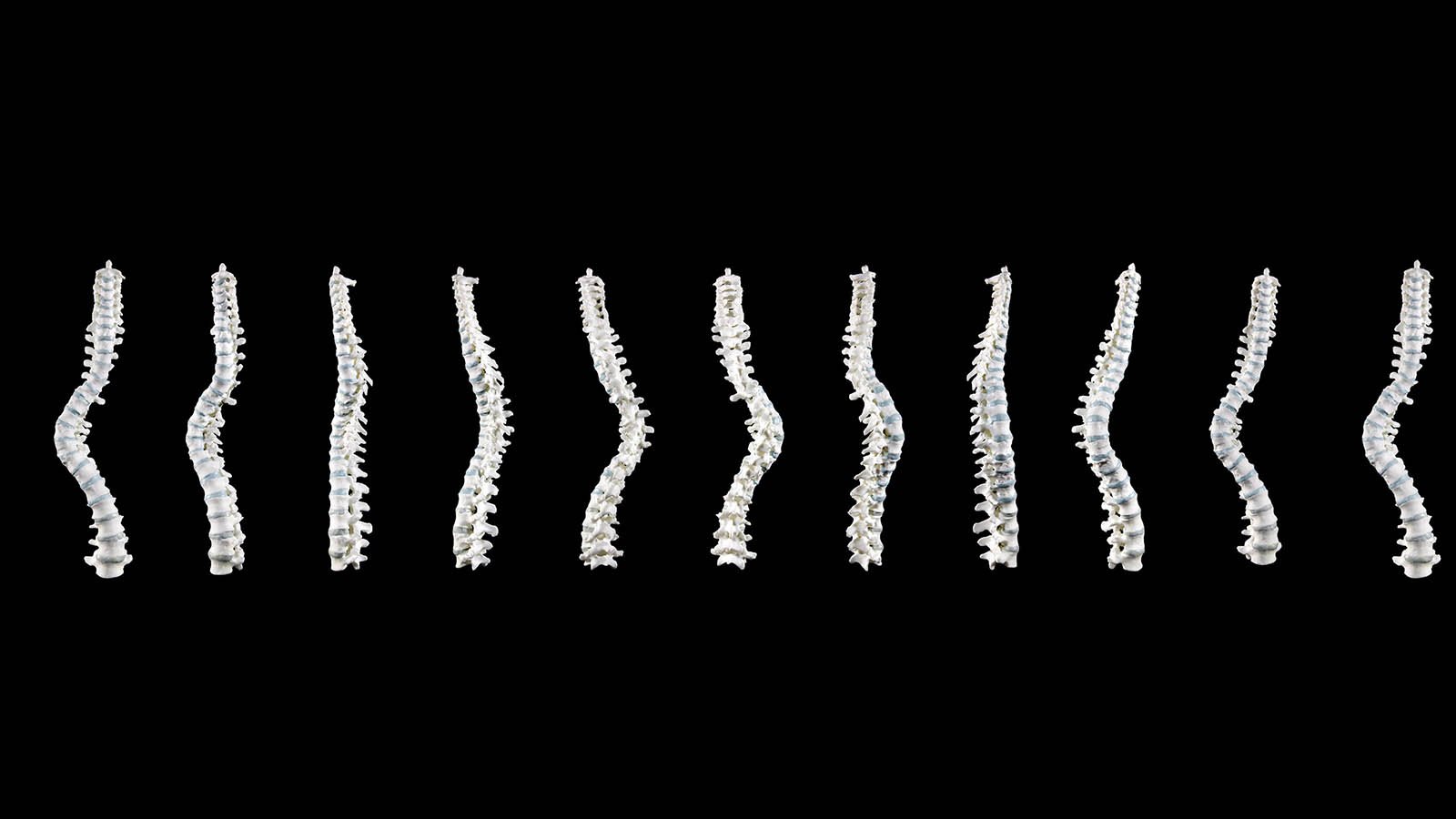

This astonishing tradition of delusion is alive and well. You have all heard how the remains of Richard III were discovered under a car park in 2012. Last week, researchers at the University of Leicester announced that they had made a 3D model of Richard’s spine. For decades, good old Shakespeare has been accused of concocting the idea, in service to Tudor propaganda purposes, that Richard was a deformed “hunchback.” (The word he used was actually “bunch-back’d.”) But many other contemporaries and near-contemporaries referred to some kind of Ricardian spinal deformity.

And this “tradition” was right, just as analogous traditions had been right about Richard’s last resting place. Richard did not have kyphosis, which causes the classic hunched back, but the more familiar scoliosis. The degree of curvature would not have incapacitated Richard, but would definitely make you pause if you saw someone on the street with it tomorrow. The dude’s back was, well, bunched.

Yet the official reaction from the Richard III Society, whose members and fellow travellers called the king’s deformity an “invention” for decades, is not that Shakespeare was right and is owed about a billion apologies. It is: “See? It wasn’t kyphosis!” If you have built an entire society and a cottage industry around a premise, you do not let go easily. So spare a thought for poor Shakespeare. He has certainly been vindicated by this discovery—whoever the heck he was.