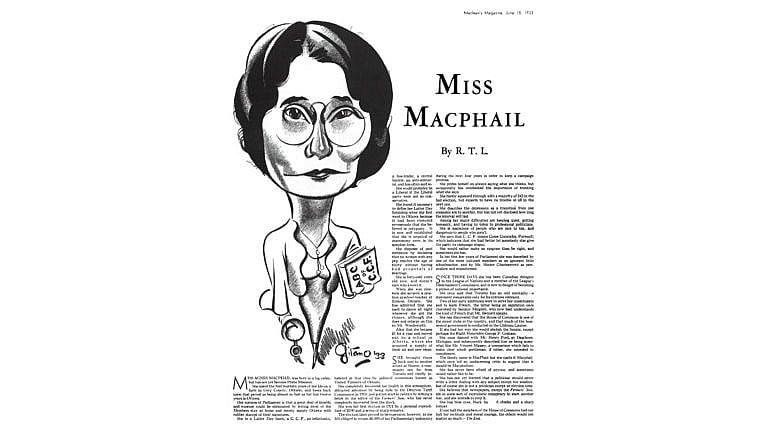

This 1933 profile of Agnes Macphail captures how the first woman MP was perceived

‘It had been rumoured erroneously that she believed in polygamy. It is now well established that she is sceptical of matrimony even in its simplest form.’

Share

This article was published on June 15, 1933. Read the story in the Maclean’s archive.

One hundred years ago, on Dec. 6, 1921, Agnes Macphail became the first woman elected to the House of Commons. This wry Maclean’s profile, written by Charles Vining under the pseudonym of R.T.L., gives a glimpse of how she was perceived a dozen years into her political career.

Miss Agnes Macphail was born in a log cabin, but has not yet become Prime Minister.

She spent the first fourteen years of her life on a farm in Grey County, Ontario, and looks back upon that period as being almost as bad as her last twelve years in Ottawa.

Her opinion of Parliament is that a great deal of trouble and expense could be eliminated by letting most of the Members stay at home and merely supply Ottawa with rubber stamps of their signatures.

She is a Latter Day Saint, a C. C. F., an inflationist, a free-trader, a central banker, an anti-militarist, and has often said so.

She would probably be a Liberal if the Liberal party were not so conservative.

She found it necessary to define her Latter Day Saintship when she first went to Ottawa because it had been rumored erroneously that she believed in polygamy. It is now well established that she is sceptical of matrimony even in its simplest form.

She disposes of past romances by declaring that no woman with any pep reaches the age of thirty without having had proposals of marriage.

She is forty-odd years old now, and doesn’t care who knows it.

When she was nineteen she secured a position as school-teacher at Kinloss, Ontario. She has admitted that she used to dance all night whenever she got the chance, although she does not enlarge on this to Mr. Woodsworth.

After that she became ill for a year and moved out to a school in Alberta, where she acquired a supply of fresh air and new ideas.

***

She brought these back east to another school at Sharon, a community not far from Toronto and chiefly inhabited at that time by political economists known as United Farmers of Ontario.

She completely recovered her health in this atmosphere, attracted attention by being rude to the Drayton Tariff Commission in 1920, and got her start in politics by writing a letter to the editor of the Farmers’ Sun, who has never completely recovered from the shock.

She won her first election in 1921 by a personal expenditure of $200 and a series of sharp remarks.

The election later proved to be expensive, however, as she felt obliged to return $6,000 of her Parliamentary indemnity during the next four years in order to keep a campaign promise.

She prides herself on always saying what she thinks, but occasionally has overlooked the importance of thinking what she says.

She barely squeezed through with a majority of 243 in the last election, but expects to have no trouble at all in the next one.

She describes the depression as a transition from one economic era to another, but has not yet disclosed how long the interval will last.

Among her major difficulties are keeping quiet, getting homesick, and having to listen to professional politicians.

She is suspicious of people who are nice to her, and dangerous to people who aren’t.

She says that C. C. F. means Come Comrades, Forward; which indicates that she had better let somebody else give the party its campaign slogan.

She would rather make an epigram than be right, and sometimes she has.

In her first few years of Parliament she was described by one of the more cultured members as an ignorant little schoolteacher, and by Mr. Hector Charlesworth as pert, shallow and misinformed.

***

Since those days she has been Canadian delegate to the League of Nations and a member of the League’s Disarmament Commission, and is now in danger of becoming a person of national importance.

She once said that Toronto has an odd mentality—a statement remarkable only for its extreme restraint.

Two of her early ambitions were to serve her constituents and to learn French, the latter being an aspiration once cherished by Senator Meighen, who now best understands the kind of French that Mr. Bennett speaks.

She has discovered that the House of Commons is one of the nicest clubs in the country, and that much of the business of government is conducted in the Château Laurier.

If she had her way she would abolish the Senate, except perhaps the Right Honorable George P. Graham.

She once danced with Mr. Henry Ford, at Dearborn, Michigan, and subsequently described him as being somewhat like Mr. Vincent Massey, a comparison which fails to make clear which gentleman, if either, she intended to compliment.

The family name is MacPhail but she spells it Macphail. which once led an undiscerning critic to suggest that it should be Macphailure.

She has never been afraid of anyone, and sometimes would rather like to be.

She has not yet learned that a politician should never write a letter dealing with any subject except the weather, but of course she is not a politician except at election time.

She believes that newspapers, except the Farmers’ Sun, are in some sort of capitalistic conspiracy to start another war, and she intends to stop it.

She has blue eyes, black hair and a sharp temper.

If one half the members of the House of Commons had one half her rectitude and moral courage, the others would not matter so much.