The Mikado’s punishment doesn’t fit the crime

Outrage finally descends on Gilbert and Sullivan’s popular Orientalist operetta.

Share

I knew The Mikado would eventually be off-limits. Gilbert and Sullivan’s most popular operetta is set in a sort of theme-park version of Japanese culture. The concept of the play is that it has superficial authenticity in settings and costumes, but the story and characters have nothing to do with Japan at all. Much as science fiction would use other planets for allegories about the author’s own country, Japan in The Mikado is an allegory for England — because to an Englishman of 1885, Japan might just as well have been another planet.

For those who don’t see the allegory, the sight of a Japan where people are beheaded for flirting and women “do not arrive at years of discretion until they are 50” must seem pretty nasty, but even if you do see the allegory, there’s plenty in there that was going to work against it in a changing culture. It’s rooted in 19th-century exoticism, where Europeans gawked at theme-park versions of cultures they didn’t want to understand; it’s got the childish, albeit universal, urge to make up mocking versions of foreign names (“Titipu,” “Yum-Yum,” “Nanki-Poo”), and above all, it calls for a white company of actors to be made up and costumed as Japanese people.

Some directors considered this a problem long ago and tried to get around it; Jonathan Miller’s 1980s production for English National Opera, still in the repertory today, set the whole thing in England because Miller didn’t like the exoticism. But this isn’t an option for the New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players, whose mission statement is to perform small-scale performances of Gilbert and Sullivan in the style of the old D’Oyly Carte company, i.e. a basically 19th-century style.

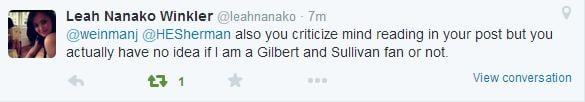

Well, since 19th-century theatre style and cultural appropriation are linked, at least whenever a 19th-century work ventures out of the home country, it was only a matter of time before this caught up with the NYGASP. This year it finally happened. A playwright in New York, Leah Nanako Winkler, saw the flyer for the show, where the actors were wearing the “traditional” (19th century influenced) costumes and makeup.

Winkler called the company’s artistic director, Albert Bergeret, three times. Her first question was how many people of Asian descent were in the show (only two, and, as Bergeret explained, they’re a repertory company where a few people do all the parts in different shows). The second time, she called him to inform him that “I’m looking at the flyer and it’s yellowface,” and when he began to say that maybe the flyer doesn’t reflect what people see in the show:

Me: (losing my s—) YOU’RE GOING TO GET INTO DEEP S— FOR THIS.

Click.

The third time she called him back, Bergeret didn’t want to talk to her and was afraid this was the start of bad press. To quote a Gilbert and Sullivan patter song from another show, “I can’t think why.”

Anyway, you know how it goes from there (but here’s the New York Times report to make it simpler). The Twitter hashtag, the “20K plus people who saw the alert and took action in such a passionate, loud, united way that couldn’t be ignored.” The company first announced they would do the show without makeup, then cancelled the thing altogether with an apology and an announcement that they would rethink the play in the future. Which of course is their right (though to say this is not “censorship” implies that only the government can censor or oppress, something only hard-core libertarians believe; calling for something to be censored isn’t always wrong, that’s all).

There was a similar controversy in Seattle last year, so Bergeret should have been prepared for something like this, and perhaps his fear of media attention is evidence that he was prepared for it, but didn’t know how to deal with it. He may have assumed that the company would benefit from a grandfather clause, given that they’re an old company doing an old play in an old-fashioned style, and should not be judged by the same standards as a company putting on a new play. Plus of course the show is not really about Japan, as G&S fans tirelessly (and tiresomely) explain, and can be distinguished from shows that actually try to convince the audience that this is what Japan is like. Or it might be that he’s just clueless about the effect of his productions, which don’t have a high artistic reputation.

But the cultural assumption is increasingly that a white actor playing a Japanese character, with or without makeup, is always unacceptable. And even if The Mikado had an all-Japanese cast, as it does when it’s performed (successfully) in Japan, it would still be a work of 19th-century exoticism, or at least a gentle parody of such works. If this is considered an unambiguously bad thing, and increasingly it is, then there is no way to do The Mikado outside of a revisionist production (and even there, some would argue that white people writing about Japan is just unsalvageable in any way). Those who have enjoyed the show as an allegory for England, and a satire of the universal tendency to imagine that all cultures are just like us, are out of luck.

Well, boo-hoo, the response might go. A few people can’t enjoy the bad thing that was all their own. Well, yes. The NYGASP’s audience has had something taken away from them that they enjoyed; this is not a change being made because of audience response. (The D’Oyly Carte company changed the play’s two instances of the “n-word” in the 1950s. When Gilbert wrote it, he was referring to white performers in blackface, but it played very differently to 1950s audiences, especially in America.) But it was rejected by people who had no intention of going to see it, based primarily on a flyer that — as the artistic director was trying to explain before he was cut off — didn’t represent how the show is experienced. This is not like the Confederate flag on government property, where people have to look at it whether they want to or not; this is a classic “if you don’t like it, don’t see it” situation.

So the idea is that even if people who don’t like the flyer don’t see the show, it does harm by perpetuating bad traditions and unequal power relationships. American Theatre‘s Diep Tran wrote:

The message sent to people of color by productions like an unreconstructed yellowface staging of The Mikado or Cry, Trojans! is basically: “You are not important enough to be respected. You don’t deserve a voice onstage. You are nothing but objects to us.”

That’s certainly a fair point. Everyone’s experience is different, and one of the irritating things about some Gilbert and Sullivan fans is their tendency to point out the allegory of the show as proof that the show is objectively non-racist, and that anyone who experiences it differently is wrong.

A person of Japanese descent is inherently an expert on one thing that I will never truly understand: how it feels to be a person of Japanese descent watching white people play-act at being Japanese. Given that fact, it’s rude to explain to people that they’re wrong to be “offended” by the representation of their culture, but that happens all the time, especially online. Someone’s personal experience is not something to be questioned or second-guessed; all we can do is learn from it.

(For example, a woman recently told me that she had always found the “Three Little Maids” song to be sexist, ever since she was was a little girl. It had never occurred to me before, and still really doesn’t, but I don’t know how the sight of three modern women acting like giggling Victorian schoolgirls comes off to a woman, and it’s not for me to tell her how she should feel.)

But when the argument shifts to the question of what is acceptable to put on the stage today, then it shifts from personal experience to questions like whether art hurts society by perpetuating negative stereotypes, and whether the cultural appropriation involved in the creation of The Mikado is benign or harmful or somewhere in between. None of the people pushing against this production are experts on these matters.

Which doesn’t mean they’re not right, just that personal experience does not automatically translate into authority on anything except your own experience. It’s wrong to question a black person’s reaction to that word in Huckleberry Finn; when discussion shifts to whether the word is artistically necessary, the premises are different, and more disagreement is possible. And discussions of The Mikado are based on things on which there is no “authoritative” answer; even the question of “yellowface” depends on what definition you’re using. But the current mentality online is summed up by the end of a popular Tumblr cartoon about white privilege: if you educate yourself, you will agree with the speaker, and if you don’t agree, you haven’t educated yourself enough. People who say they want a “conversation” often don’t really want it.

Of course the idea that The Mikado is racist certainly isn’t based on nothing. It’s not malicious, nor is it intended to represent what Japan is really like, but it’s based on the notion that Japan isn’t quite “real” and there’s no need to know anything about it apart from the superficial trappings. And yes, even though the use of the term “yellowface” is indiscriminate and at best debatable (a bit like the practice of darkening a performer’s skin to play Othello is inaccurately and ahistorically described as “blackface”), the use of makeup to make white actors “look Japanese” has uncomfortable associations with the worldwide tradition of a majority culture making fun of minorities, or taking roles that should have gone to minority actors (for example, the many white actors who played Charlie Chan). As you can tell from Gilbert’s disparaging references to blackface performers, The Mikado‘s makeup was considered very different from blackface or yellowface, since it lacked their caricatured mockery. But just because it was ahead of the curve for 1885 audiences doesn’t mean 2015 audiences see it the same way.

All of which means that if a Japanese-American doesn’t want to see The Mikado in a “traditional” production, no one could blame that person. But this was more than that: this was people who don’t want to see the play insisting that it should not be staged in that form for other people. And the people who enjoy the play are naturally not given the benefit of the doubt when they describe their own experience watching it. That they claim to understand that it’s not about Japan is just proof that they’re lying about, or in denial about, their own experience.

There’s a whole lot of mind-reading and gaslighting that goes on in this situation, where people who hate a work claim to understand it better than people who love it. I suppose sometimes that is true. But for example, people who dismiss Gone With The Wind as simply racist and pro-Confederate tend to understand it less well than the story’s fans, who also see the racism and pro-Confederate nostalgia, but also the feminist story of a potentially great woman warped by the society she was raised in, and the examination of what a society does after it’s been wiped out by a brutal war (which is just as brutal even if the society is the Confederacy or Nazi Germany). A white fan of The Mikado does not know what it’s like to be a Japanese-American watching it. Of the historical and social context of the play, the average fan probably knows more than the average non-fan. Sometimes people who don’t like a work might be entitled to have their own interpretation imposed on those who do, but it can’t be as simple as disliking the flyer.

This is a minor story, of course: a small company with a small audience that felt it necessary to pull its most popular show and rethink it. But it’s precisely because it’s such a minor story that it bothers me so much: people who didn’t want to see the production managed to get it taken away from a tiny sliver of people whose cultural preferences — 19th-century theatre in 19th-century style stagings (even bad ones) — are on the losing side in a very presentist culture.

The fact that it is a small company made it easy to punch down on. Disney’s Aladdin may be running on Broadway, an Arabian Nights fantasy full of white actors*, Orientalism and dubious Imperial associations — but it’s a big show from a big company, and no one pays attention to the complaints. The theatre has a terrible record when it comes to non-white actors and playwrights, but that’s going to take a long time to fix, if it’s fixable. But a 120-year old play with a unique reason for requiring this type of casting, performed by a company whose whole reason for existing is the link with 19th-century performance style: that’s an easy target. In an era when anything before the 1990s is considered old, there is no cultural penalty for attacking an old work and declaring your lack of empathy with its time period or its audience.

One of the many obvious arguments against what I’ve said is that marginalized groups now have a voice that they didn’t have before, and that the NYGASP now has to listen to complaints it could have ignored in the past. Its audience losing something it liked is a small price to pay. Perhaps. But everyone who tries to get a play shut down or revised thinks they’re doing it on behalf of the culturally marginalized. And people are rarely aware of their own power when they’re using it to shut down people who, in this particular situation, have less power.

Look at this post by Howard Sherman, another of the leading campaigners against the production, full of dubious and arguable statements, laying down the law that only revisionist stagings are acceptable. He even takes a shot at Trevor Nunn, a longtime proponent of diverse casting, for choosing to do a naturalistic version of Shakespeare’s history plays whose concept did not allow for that type of casting. This isn’t someone who wants diversity; it’s someone who wants all productions to be the same and to stamp out an increasingly rare production style in older plays — all while the commercial theatre goes about its business with shows like Aladdin. When he’s pounding on the cultural losers, the cultural winner never likes to think of himself as such.

Update:

1. As someone pointed out, the cast of Aladdin doesn’t have many white actors; what it doesn’t have is Middle Eastern Actors.

2. I linked to it earlier, but the best anti-NYGASP piece I’ve read is by Erin Quill, who has actually seen their production of The Mikado and found it to be terrible, full of camped-up stereotyping and featuring a character Gilbert and Sullivan definitely didn’t intend:

The Axe Coolie was a small female child who ran around the stage dressed as a male, er, an Asian male, waving a GIANT paper mache axe and shouting “High Ya” whenever she was on stage.

…TFP has checked with a past NYGASP member, that addition is a staple of Mr. Bergeret’s productions of this operetta. The conversation went something like this:

TFP: There was this kid dressed as a boy holding a giant (Gets cut off)

TFP’s Friend: “Oh, the Axe Coolie? Yeah, he’s always in there.”

I’d suggest reading the whole thing, as well as this 2003 review of the NYGASP’s production by Anne Midgette.

Update 2: This is absolutely true.