‘Charlie Hebdo’ and the revenge of the old religion

Colby Cosh on the high-voltage power—and the graven tragic consequences—of the image

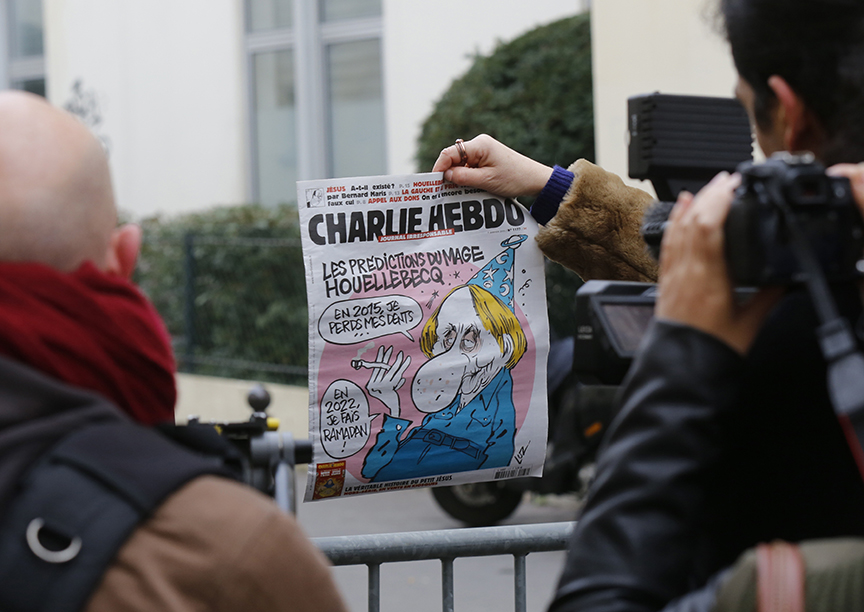

A man holds up the front page of the latest issue of Charlie Hebdo, a satirical magazine, which shows a caricature of French author Michel Houellebecq. At least 12 have died in a shooting at the Charlie Hebdo offices. (Jacky Naegelen/Reuters)

Share

One of the things about this morning’s massacre at the offices of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo is that it sort of puts us writers in our place. Nothing I could ever put into text about Muslims is ever likely to get me killed; it is images that get people worked up. The conscious, intensifying nastiness of Charlie Hebdo‘s cartoons about Muhammad were not what got the magazine in trouble with the faithful in the first place: It was that they dared to depict the Prophet visually at all—a sort of double blasphemy under Islamic norms.

The Abrahamic faiths all have an iconoclastic propensity that bursts forth every few hundred years, sometimes into bloodshed. It has been preserved in a purer, more concentrated form in Islam, but the superstition is present in, say, any old Calvinist church. It goes back to (but surely beyond) the Hebrew God’s commandment against “graven images.” In most Christian sects, this is now taken to be a warning against active idolatry and, read that way, but in the original language, it is a pretty clear admonition not to make any inscribed likeness. Images seem to have been dreaded as a species of lie, the way someone of extremely literal mind might consider a novel to be a lie.

It is hard for a civilized person to think consciously of images in this way, to be so in awe of the power of a picture that one might treat it hostilely as a rival to the deity. But when you go to work for the news, you learn pretty quickly that the comics are the section that is hardest for an editor to make changes in, or even exercise basic quality control over, and that a politician will hold a grudge against an unfriendly editorial cartoonist for a hundred times longer than he can against any crusading columnist who berates him with mere language. (Bill Vander Zalm probably still hasn’t forgiven Bob Bierman, who’s been dead for six years.)

The French press is, for some reason, much better at recognizing the authority of the illustrator than is the English-speaking world. Charlie Hebdo‘s martyred cartoonist Stéphane “Charb” Charbonnier was the editor-in-chief of his publication, a situation that would be unusual in Britain or the U.S.—unusual to the point of seeming unnatural. There isn’t any real reason for it, anything about writers that makes them inherently more capable of managing and judging artists’ or designers’ contributions than an artist would be of judging a writer’s.

Anglos are merely trained to think that the text of a magazine is somehow its real content and that the rest is decoration—stuff that ought to be done right but that is nonetheless peripheral. It might be closer to the innate truth to think of it the other way around. Writers are mere asserters, describers, quarrellers: It is pictorial artists like Charb who are playing for the real stakes. You can’t argue with a cartoon.

Which, I suppose, has something to do with the reporting of the attack on Charlie Hebdo headquarters today. In the English-speaking world, mere scribes who have been anointed editors of television networks and wire services are deciding to blur out the work of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists, or show it from a few yards away, that it might not be encountered properly. They have to make decisions in a moment about a mainline megavolt power they are not accustomed to handling. In a scurrilous way, they are really paying tribute.