magazines

‘Charlie Hebdo’ and the revenge of the old religion

Colby Cosh on the high-voltage power—and the graven tragic consequences—of the image

Taking the shine off those gold-plated pensions

Maclean’s editors on the changes to MP’s pensions; and on the death of Newsweek

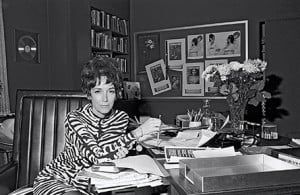

Advice from a former Cosmo editor: how to make an impression at the office

No guts, no glory for working girls

Why I’m sick of alumni magazines

The requests for money never cease

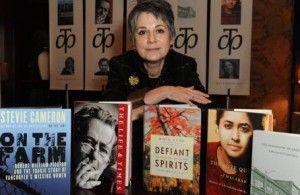

Where’s the sizzle in Canada’s non-fiction?

The Charles Taylor Prize always brings out many very good writers. It rarely takes my breath away.

Le castor fait tout

I wonder if any of the other Macbloggers have been straining at their imaginations trying to find a PG-rated way to talk about the name change over at Canada’s second-oldest magazine. It took me a while to remember that General Semantics has an answer for this. So: The Beaver, now to become Canada’s History, was named in 1920 for what we’ll call beaver1, the rodent Castor canadensis. The periodical was obliged to make the change because of jokes about and search-engine confusion with beaver2, a colloquialism for an anatomical neighbourhood in the human female.

These days the devil recycles Prada

The elitist Anna Wintour of this movie wouldn’t have been caught dead in Queens

So sexy it hurts

Women’s magazines have long had a bad rap as the source of female insecurity, what with all those images of beautiful models. (Or articles suggesting all kinds of unbeautiful things women do, like make orgasm faces, but that’s another matter.)

Weekly newsmagazine in freefall

And once again, it’s not us.

Magazine shuts down all of its blogs

Don’t worry. It’s not us.

The news, when we get around to it

I’m still digesting this extraordinary piece by New Yorker writer George Packer about what he believes is the terminal crumbling of the conservative coalition that has dominated U.S. politics for most of my lifetime. As prognosis it’s arguable but at least plausible. As diagnosis it’s fantastic — the first third of the piece, on what Pat Buchanan and Dick Nixon were up to, is a tale told a thousand times but still full of lessons for students of politics. And as a metaphor for what Patrick Muttart, Stephen Harper and a few others have been up to, it is invaluable, and helps explain why events like this one deserve more attention than they sometimes get. I’ll share a few more thoughts after the jump, but first I want to complain about why you almost certainly haven’t had a chance to read Packer’s article in print yet.

In New York and most large U.S. cities, Packer’s article and the entire rest of that issue of the New Yorker has been on newsstands for six days and will come down tomorrow, to be replaced by the next issue. That’s the case with most weekly magazines, which come out on Monday. (Maclean‘s comes out on Thursdays lately, Time and The Economist on Fridays, but New York, Newsweek and a bunch of others are Monday weeklies.)

In Canada when I left for France last year, the same was true: magazines were hitting the stands in Ottawa, Montreal and most other large cities on the same day as in Manhattan. It’s one of the perks of living in a large civilized country. Or so I used to think, because when I got back home this spring, I was floored to discover that almost all large U.S. weeklies are now getting to Ottawa, not on the day they’re published; not three days later, so the Mondays would be sharing space with the Thursdays (i.e., Maclean’s); nor even a week after publication date… but a week and three days after their U.S. street date. So if you don’t like reading Packer’s article online, you’re going to have to either fly to Manhattan tonight or wait until Thursday, ten days after it was published, for it to get onto magazine shelves in Ottawa.

Blame these guys. Jimmy Pattison’s News Group is, my local retailer tells me, responding to the general collapse in sales of print magazines by not working so hard to get the product to market. It used to be so hard to get a magazine to you on the day it was published. So now they’re gonna take 10 days to get a weekly magazine to you. At least that’s the situation in Ottawa. I’d be obliged if frequent magazine buyers in other cities would use the comment section to fill me in on the situation in your town.

As an employee of a magazine that has lately deployed significant resources to improve its historically very spotty distribution coast-to-coast, I’m delighted that a magazine distributor is so eager to kneecap so much of my competition. As a consumer, I’m less thrilled. As a backseat driver, I’m baffled: if the consumer base for your product is declining, why would you want to alienate buyers with radically deteriorating service? When I arrived at The Gazette in 1989, that newspaper’s reader base had been fleeing down the 401 for years. The response from circulation was to build the hungriest, fastest-responding, most customer-oriented reader sales department in Quebec. Perhaps it was a naive response. Anyway, thanks to The News Group for driving so many readers of U.S. weeklies to the internet and to the Canadian alternative. I guess.

Anyway. Back to Packer. One reason I’m not sure his analysis is directly translatable to the Canadian scene is that our federal politics has been dominated by the major left-leaning party, not the major right-leaning party, for the past 40 years. So Harper’s game is new and relatively fresh here, and simple fatigue is less of an obstacle to conservative Canadian strategists than it is to conservative American strategists. So the Buchanan-Nixon experiment is, at this late date, more germane here (I’m only guessing, frankly, but this feels right to me) than it is in the U.S. From Packer’s story:

“’What we talked about, basically, [Buchanan says,] was shearing off huge segments of

F.D.R.’s New Deal coalition, which L.B.J. had held together: Northern

Catholic ethnics and Southern Protestant conservatives…’ Buchanan grew up in Washington, D.C., among the first group—men like his father, an accountant and a father of

nine, who had supported Roosevelt but also revered Joseph McCarthy. The

Southerners were the kind of men whom Nixon whipped into a frenzy one

night in the fall of 1966, at the Wade Hampton Hotel, in Columbia,

South Carolina. … “In order to seize the Presidency in 1968, Nixon had to live down his

history of nasty politicking, and he ran that year as a uniter. But his

Administration adopted an undercover strategy for building a Republican

majority, working to create the impression that there were two

Americas: the quiet, ordinary, patriotic, religious, law-abiding Many,

and the noisy, élitist, amoral, disorderly, condescending Few…