‘I pay the rent, what do you do?’

On Post-Its, bills, empty toilet paper rolls: notes to and from the roommates from hell

Share

Updated April 20, 2018

During her student years, rising prices drove from Oonagh O’Hagan from charming Notting Hill to a mouse-infested apartment above a Perfect Fried Chicken take-out in South London, shared with four unknown “eccentrics.” Glasgow-raised, with a residual Scotch accent and a cheeky, self-deprecating sense of humour, O’Hagan got along famously with all but one who, it became clear, was a “pathological” note-writer with a two-per-day habit. Insular, frosty and prone to “brutal, rigid, Presbyterian thinking,” says O’Hagan, the note writer enjoyed patchwork and, to her roommates’ endless curiosity, had affixed seven locks to her bedroom door. “Like something from a Dickens novel, she would lock herself into her room—as if she was weaving some sort of huge rope ladder to get out the window.”

“Every time you came in from work, you’d see the fridge, and you’d be like, ‘Oh my God, another note!’ ” says O’Hagan, now a member of the Fashion and Textiles faculty at the famed British art school Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design, and fashion designer, who’s consulted for Burberry and Louis Vuitton. Spurred by twin anthropological and curatorial urges, O’Hagan found herself collecting the notes (some were “really hostile and vile”). At first, the massive pile next to her bed depressed her. Then, she says, it struck her as “quite funny.”

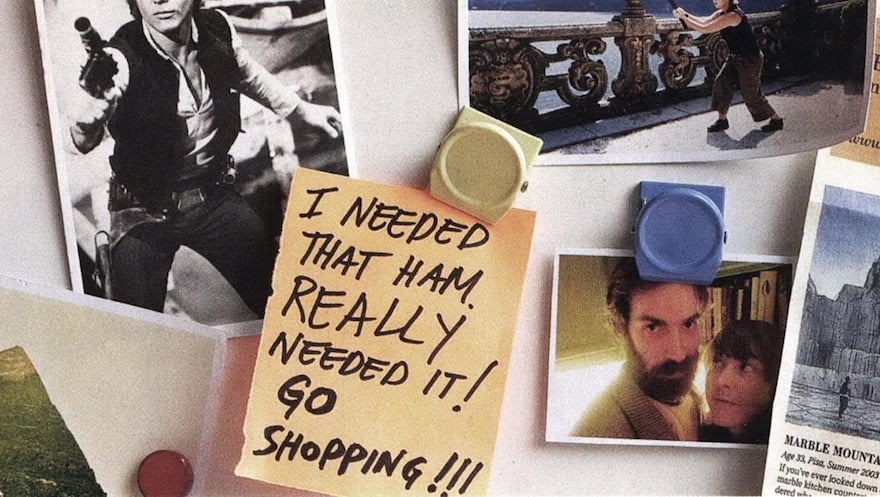

She quickly realized she was far from alone. She found a whole strata of society like her: some accused of late-night toilet flushing, of having thieved ham, drugs or shampoo, some the godless recipients of Xeroxed Biblical excerpts. She asked friends to donate their notes and started a website, flatmatesanonymous.com, where people could post their own. So began I Lick My Cheese: And Other Notes From the Frontline of Flat-Sharing (Abrams Image), a 2009 compilation of real messages scribbled on Post-Its, bill reminders, and empty toilet paper rolls. Through some of the angriest, ickiest and more poignant missives ever passed from one roommate to another, O’Hagan has plumbed darker recesses of human nature than even Dostoevsky.

The notes range from barbed gems like “The washing up you didn’t do is in your bed. Cheers, Al” or “I pay the rent, what do you do?” to “Daniel: I’m off to Savannah. Taken bed sheets and wok. Enjoy Whitechapel you s—!” There’s indelicate (“I am sorry I had to put my pee in the fridge. I sealed it in a plastic bag, then this box, then taped it shut”), alarming (“Could somebody please explain why my door has magically come off its hinges and is lying in the middle of my room?”) as well as smoke and mirrors (“You know that I know that you know that I know that you took it . . . So give it back”).

The frustration of dealing with those with low-level hygiene and social skills shines throughout. There are passive-aggressive reminders, like the one about a two-foot bong “thoughtfully left on display on the coffee table” during a grandparent’s visit, as well as aggressive-aggressive ones: “If you piss on the seat/floor one more time I will personally see to it that you NEVER WALK AGAIN.” And then there’s plain crazy: “Frank, when I said you could clean the kitchen, I didn’t mean for you to paint it. You have just painted over everything, including all the dirt, in white emulsion. It looks like a blizzard! Do you not know how to clean.” (A week later, its author moved out on Frank, who shrugged that he was an “all-or-nothing type.”)

Despite tight living quarters and “not-completely-optional” pairings, however, these types of rooming situations are not all bad, O’Hagan avers. Like an “Aboriginal walkabout,” it’s a “massively rewarding” rite of passage, she says. At the end, you emerge immensely more durable, “less selfish,” and wise to your own neuroses and habits, “because you have to think, ‘Is this going to annoy somebody?’ ”—skills that transfer to the workplace and beyond.

For O’Hagan, the book also had a good “knock-on effect.” After 10 years of apartment-sharing, the generous advance enabled her to buy her own North London flat and marry her boyfriend, a fellow Glaswegian. It took her a while, however, to get used to the idea that she no longer has to store all her food on one shelf in the fridge.