James Bond: The evolution of an iconic franchise—and the coolest secret agent of all time

On the eve of Bond 25, Brian D. Johnson looks back at how 007 has changed with the times—from Connery’s droll menace to Craig’s tortured thuggery—while always remaining invincible and immune to any style but his own

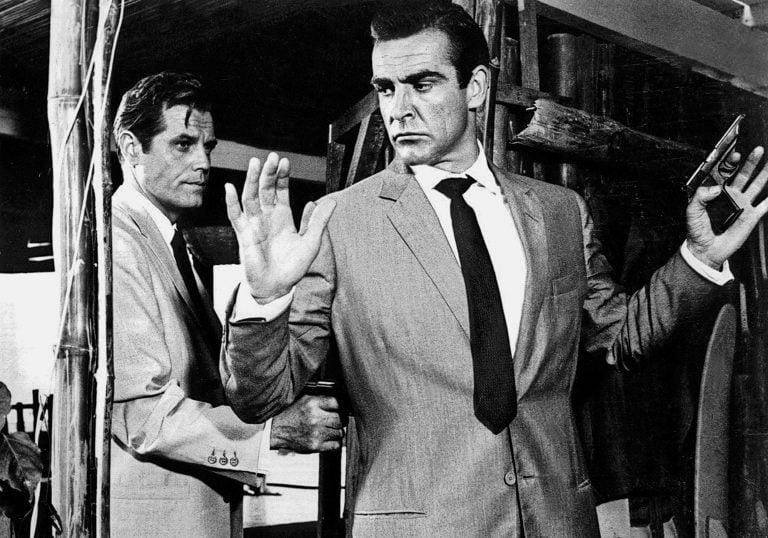

On Oct. 5, 1962, James Bond made his first movie appearance in ‘Dr. No,’ which starred Sean Connery and Jack Lord (Everett Collection)

Share

This story originally published in print in February 2020.

Bond. James Bond. He was born in Jamaica, in a house named Goldeneye on a cliff overlooking a bucolic private beach. That three-bedroom bungalow is where Ian Fleming wrote Dr. No in 1958, and another 11 novels that would turn 007 into a magic number. And the beach is where the first actor to play Bond spied the first Bond girl, as Sean Connery poked his head through the bushes and watched Ursula Andress emerge from the sea in a white bikini, a knife slung from her waist, singing the calypso strains of Under the Mango Tree. It was a simpler, dumber time. Louche playboys were cool. Ogling was just a heightened form of espionage. And in a barely post-colonial world, where privilege was still synonymous with pleasure, Bond offered a risqué escape from the Cold War. One of his biggest fans was President John F. Kennedy, who watched From Russia With Love at a private screening in the White House, weeks before his assassination.

Now Goldeneye has expanded to become a luxury resort. The name of 007’s creator has migrated to the Ian Fleming International Airport 10 minutes down the road. And Bond movies are bigger than ever. After 57 years, they constitute one of the longest-running film franchises in history, with a lifetime haul of more than US$8 billion at the box office, the third largest after the Marvel Cinematic Universe and Star Wars empires—though the comparison hardly seems fair, considering they enlist entire teams of sci-fi superheroes armed to the gills with sci-fi powers and special effects, while James is still a one-man band who drives to work behind the wheel of an Aston Martin. He’ll gun a motorcycle up a staircase, or sled an airplane down a ski hill, but he’s all about keeping it physical.

This spring heralds a significant milestone for 007. In the first week of April, Universal and MGM will release No Time to Die, the 25th movie in the official canon of Bond movies generated by Britain’s Eon Productions (which doesn’t include 1967’s Casino Royale spoof starring David Niven as “Sir James Bond” and Connery’s 1983 outlier, Never Say Never Again). Despite the title of the new film, after threatening to walk away more than once, Daniel Craig has sworn that No Time to Die will be his final Bond performance. It’s the most expensive film in the history of the franchise, with an estimated budget of US$250 million. It may also be the most concerted effort yet to drag cinema’s most iconic alpha male kicking and screaming into a world of gender fluidity, obscene wealth, viral racism and catastrophic climate change. It would be enough to drive Ian Fleming’s Bond to drink.

READ: The James Bond film franchise is actually a family business. Meet the Broccolis.

No Time to Die’s generic title has a retro echo, riffing on a declension that includes You Only Live Twice (1967), Live and Let Die (1973), Tomorrow Never Dies (1997) and Die Another Day (2002). But the movie appears to be straining for relevance so hard that it’s not clear if the No Time to Die refers to its hero or the planet. Its villain, played by a disfigured Rami Malek, is plotting to kill off the world’s oceans with a form of lethal algae (as if they’re not dying fast enough as it is). Craig, meanwhile, is driving a sleek, eco-conscious hunk of luxury—Aston Martin’s all-electric V12 Rapide E, one of a limited edition of 155 four-door coupes priced at over $400,000 apiece. But the headlights flip into Gatling guns. No matter what tech Q throws at him, James remains the ultimate Analog Man.

The British press, meanwhile, have reported that the film’s producers eliminated plastic water bottles on set and banned the phrase “Bond girl.” And it seems every woman who crosses his path in No Time to Die is fiercely independent. Léa Seydoux’s sultry Dr. Madeleine Swann—who rode off into romantic bliss with Bond at the end of Spectre (2015)—is back, and the trailer shows him seething with rage over her “betrayal.” While the story is not based on any of the novels, it rewires the DNA of the Bond Universe to bring back Christoph Waltz as the cackling incarnation of Blofeld, Bond’s deceased arch-enemy. The script has 007 pulled out of a quiet retirement in Jamaica and forced to team up with a formidable Black female agent (Lashana Lynch), who is clearly nobody’s Bond girl. “I didn’t want someone who was slick,” Lynch told The Hollywood Reporter. “I wanted someone who was rough around the edges and who has a past and a history and has issues with her weight and maybe questions what’s going on with her boyfriend.” With Naomie Harris returning for her third film as Moneypenny, that puts two Black British actresses from Jamaican families in lead roles. In a shoot that ranged from the U.K.’s Pinewood Studios to locations in London, Italy and Norway, 007 returns to Jamaica for the first time since 1973’s Live and Let Die, in which it played a fictional country.

The production is rife with firsts. An anomaly in a realm of digital blockbusters, it was shot on film and is the first Bond movie to use large-format 65mm Panavision and IMAX cameras. It’s the first to cast a Cuban woman in a lead role, with Craig recruiting Ana de Armas, his co-star in Knives Out. It’s also the first directed by an American or someone of Asian heritage—filmmaker Cary Joji Fukunaga (Beasts of No Nation) is both. And Fleabag sensation Phoebe Waller-Bridge, brought on by Craig to tweak the script, is the first female screenwriter on a Bond film since 1963 (Johanna Harwood had credits on Dr. No and From Russia With Love). Craig, however, was furious when a Sunday Times reporter asked if Waller-Bridge was hired to make Bond more representative of the times. “Look, we’re having a conversation about Phoebe’s gender here, which is f–king ridiculous,” he said. “She’s a great writer.” And Waller-Bridge swiftly dismissed those who question Bond’s relevance because of how he treats women. “That’s bollocks,” she said. “He’s absolutely relevant now. The important thing is that the film treats the women properly. He doesn’t have to. He needs to be true to this character.”

READ: In a comedy about queer South Asian identity, a yogurt pot can be more than a pot of yogurt

What’s more significant about No Time to Die than all its firsts is that Craig’s fifth Bond movie will be his last. He’s the third-longest-serving 007 after Roger Moore and Connery, who both made seven films. And he has done more than anyone to transform the franchise, while refusing to get swallowed up by it. Connery fell into the role with an aplomb that made him an instant star, and then never escaped it. But he set the template for all his successors. Moore refashioned the character as a suave lounge act that devolved into camp and farce. Pierce Brosnan soldiered through his tour of duty, enduring the most pedestrian phase of the franchise. It was like watching a competent cover band do Bond. But Craig attacked the property like a punk on a mission, as if torn between redeeming and incinerating his mandate. Aside from the visceral force that he brought to the character, he applied a laser intelligence to the franchise both on camera and behind it, raising its pedigree with serious talents like Sam Mendes (Skyfall).

From the beginning, Craig didn’t inhabit the role so much as infiltrate it. Burrowing into Fleming’s novels, he set out to restore the character’s core of inner turmoil and professional cruelty. And he’s been chafing against the tropes and gimmickry of the formula ever since he ordered a vodka martini in Casino Royale and, asked if it should be shaken or stirred, snapped, “Do I look like I give a damn?” But no matter how hard he tries to exert control over the franchise, Craig’s frustration with it only seems to intensify. He’s still an aging mortal overwhelmed by a machine of movie-making that outlasts anyone who steps behind the wheel. In that sense, he operates like a double agent, toggling between hero and anti-hero in a dystopian franchise that he tries to subvert at every turn. His resentment and impatience are palpable, in and out of character. Even his charm is weaponized with cold-blooded intention. Whether or not Craig is the best Bond of all time, he’s certainly the most ruthless, and the most vulnerable. He’s the spy who is forever coming in from the cold.

On the press tour for Spectre, when a journalist from Time Out asked if he would make another Bond film, Craig replied: “I’d rather break this glass and slash my wrists . . . All I want to do is move on . . . If I did another Bond movie, it would only be for the money.” Craig’s efforts to make Bond real have taken their toll. He lost two front teeth in a fight scene on the set of Casino Royale, had surgery to repair a shoulder separation incurred in Quantum of Solace, and underwent knee surgery after tearing his meniscus during a brawl in Spectre. But you still get the sense that he’s a character actor trapped in the body of an action hero. And when he’s not being Bond, he delights in stunts of a different kind, shape-shifting his persona from Joe Bang, the nut-job safe-cracker in Logan Lucky, to Benoit Blanc, the debonair detective in Knives Out, whose southern accent is so arch that you wonder if it’s the character, not the actor, who’s faking it.

But being a Bond, like being a Beatle, doesn’t wear off. No matter what twists Daniel Craig’s career takes, it’s what he will be remembered for. It’s the reason that, like Connery and Moore, he’ll likely get a knighthood for his service as a cultural agent for Queen and country. And whoever inherits the role—Idris Elba, Tom Hardy, Richard Madden and Benedict Cumberbatch are among the plausible candidates—will be judged by an impossible standard. When Craig was cast, there was outrage that he was blond. The next 007 might be Black or Asian . . . but perhaps not female, an idea with advocates that range from Idris Elba to Pierce Brosnan—but which irritates Craig’s wife, Rachel Weisz, who told the Telegraph, “Women should get their own stories.” Weisz said that Fleming worked hard to create a character that is “particularly male and relates in a particular way to women.” In other words, a female Bond wouldn’t be Bond. For the royal family of movie franchises, male progeniture is part of 007’s DNA—and a legacy that is firmly rooted in a seismic moment of pop culture almost six decades ago.

It was the year the Rolling Stones played their first gig and Marilyn Monroe took her last breath. The year Nelson Mandela began a 27-year stint behind bars and John F. Kennedy vowed to put a man on the moon. The Cuban Missile Crisis was about to push the world to the brink of nuclear Armageddon. And on Oct. 5, 1962, Bond made his screen debut in Dr. No, the same day the Beatles released their first single, Love Me Do.

The two milestones are not unrelated. Both Bond and the bands that would spearhead the British Invasion emerged at the dawn of the swinging sixties, and put a spin on pop culture that is still reverberating. Both took the male fashions of the day—cool irony, deadpan wit and brazen promiscuity—in opposite directions. With his licence to kill, and seduce, the clean-cut 007 was a paragon of retro style from the start, a macho smoothie forged in the ’50s by author Ian Fleming and left in the dust of the sexual revolution. While the Beatles, the Stones and David Bowie would melt down the masculine mystique in a river of drugs and androgyny, James Bond would remain crisp, suave and insensitive, a playboy predator fuelled by vodka martinis and room-service champagne.

“My dear girl,” Sean Connery’s 007 told Bond girl Shirley Eaton in Goldfinger, “there are some things that just aren’t done, such as drinking Dom Pérignon ’53 above 38 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s just as bad as listening to the Beatles without earmuffs.” As a pop reference, it must have seemed terribly au courant at the time, but was rendered instantly square: Goldfinger came out in 1964, seven months after the Beatles electrified a generation on the Ed Sullivan Show.

Bond fashions have come and gone over the years as six actors have tried on the role. From Connery to Craig, the arc of the character has swung from droll menace to camp swagger and back again. His pose has softened and hardened with the times, along with the women. The first generation of Bond girls were Barbie playmates, pure sex objects. As feminism nipped at Bond’s heels, the women mutated into dominatrix ninjas, while Bond, always the central sex object, morphed from Connery’s furry man of leisure to Craig’s hard-bodied, hard-working, brutally efficient thug. But the beauty of Bond is that he’s a classical icon: obdurate, invincible and immune to any style but his own. Each casting syncs the character to the culture, yet the basic formula for the films has retained an uncanny consistency.

For a generation raised on comic books and black-and-white TV, discovering Bond was like discovering sex. Until then, we had doted on men in capes, tights, masks, leather chaps and coonskin caps—a carnival of superhero drag that included Superman, Batman, Roy Rogers, Davy Crockett, Zorro and the Lone Ranger. Then along came this guy in a suit. His idea of camouflage was to throw on a tuxedo. A secret agent without a secret identity, he was our first grown-up icon of male fantasy. Since then, comic-book superheroes have conquered Hollywood, but Bond, classic and straight-up, remains cinema’s most durable action hero, sex symbol and brand.

READ: Simu Liu is on the cusp of superstardom. But that isn’t his end game.

Dr. No didn’t just launch film’s longest-running franchise. Even more remarkable, it has remained a family business for almost six decades, controlled by London’s Eon Productions, which was founded in 1961 by American producer Albert “Cubby” Broccoli and his Canadian partner, Harry Saltzman. Now that the founders are both deceased, the movies are produced by Cubby’s daughter, Barbara Broccoli, and his stepson, Michael G. Wilson.

In half a century, budgets have skyrocketed, digital effects have upstaged stunts, and Commander James Bond has outgrown the Cold War to battle new breeds of international terror. But the formula remains unchanged from the one laid down in Dr. No right from the opening frames: the prematurely digital 007 logo, the gun-barrel view of Bond firing through the fourth wall, the descending curtain of blood, and the pop-art credits playing over dancing female silhouettes—clothed for the first and only time.

Under the hood, nearly all the familiar elements were in place: the casino table, the coastal car chase, and all that lounging around in swimsuits and bathrobes, flashing equal opportunity expanses of skin. When Ursula Andress stepped out of the sea at Goldeneye, she set the bar for all the Bond girls to come, while Miss Moneypenny—portrayed by Canadian actress Lois Maxwell in 14 movies—held down the MI6 fort as 007’s frustrated office wife. Dr. No also established the arc for the basic Bond mission: travel to an exotic clime, invade the sliding-door fortress of a sadist bent on world domination, become both his tortured prisoner and pampered guest, engage the soft-spoken lunatic in sophisticated repartee, and escape with the girl after foiling the villain’s doomsday scheme at the last possible moment.

Sean Connery, who set the style for 007, is still widely regarded as the definitive Bond. But he wasn’t the first choice. That would be Broccoli’s friend Cary Grant, who was passed over because he wouldn’t sign on for more than one film. Other debonair rejects included James Mason, David Niven and Rex Harrison. “I wanted a ballsy guy,” said Broccoli. “Put a bit of veneer over that tough Scottish hide and you’ve got Fleming’s Bond instead of all the mincing poofs we had applying for the job.” Connery had been a milkman, labourer, artist’s model, coffin polisher and bodybuilder—placing third in a Mr. Universe contest. Before being cast as 007 at 32, he had been honing his acting chops for a decade in stage, screen and TV work, including the title role in a 1961 CBC production of Macbeth directed by Paul Almond. And like Commander Bond, he’d even spent some time in the Royal Navy, with tattoos to prove it.

It was Terence Young, Dr. No’s Cambridge-educated director, who groomed the six-foot-two working-class Scot, teaching him how to dress, how to walk and how to open a bottle of champagne. “All the little touches, that’s the way Terence was,” recalled Eunice Gayson, who played Sylvia Trench, the first Bond girl to appear on screen. “He had style, he had élan. In those days Sean was very raw. Terence took him to his tailor and to his hairdresser and really gave Sean the confidence to be James Bond.” The hairdresser, however, would be working with a toupée: already balding, Connery wore a rug from the start.

With the first shot of Connery introducing himself at a gambling table in Dr. No with a cigarette—“Bond,” he said, snapping his lighter shut to mark the pause, “James Bond”—no one has owned those words with such dry authority. Young recalled that Connery first spoke the line all at once and it wasn’t funny. With the pause, “suddenly it was a laugh.” From the start, the movies injected a sense of humour that Fleming’s hard-boiled prose did not allow. Young, who went on to direct From Russia With Love and Thunderball, felt it was essential to lighten the mood because the films were so risqué for the times. Flying into Jamaica to shoot Dr. No, he remembers telling Connery, “For Chrissakes we have to make this picture a little bit amusing, if for no other reason that it’s the only way we’re going to get away with murder. A lot of things in this picture—the sex, the violence and so on—if they’re played straight, we’re never going to get past the censors.”

READ: Blown away: Glassblowing’s blazing hot moment on Netflix

Dr. No was filmed on a budget of $1 million, meagre for a movie that had to convey an air of opulence. Like every Bond movie that came after, it combined interiors filmed at Britain’s Pinewood Studios with stunning locations—including Jamaica’s north coast, not far from Goldeneye, the beach house where Fleming wrote all the Bond novels. Jamaica had just won independence from Britain, and the film is infused with the pre-reggae rhythms of a culture about to make its own indelible mark on pop culture. Dr. No became an early source of national pride, ironic considering its hero was an anachronism from a colonial past that Jamaica was shaking off. The movie’s location manager, meanwhile, was none other than founder of Island Records Chris Blackwell, who would produce Bob Marley. Blackwell, who bought Goldeneye from Marley after Fleming’s death, was to the Bond manor born. His mother, Blanche, was Fleming’s mistress and muse, and she’s been credited with inspiring both Dr. No’s Honeychile Rider and Goldfinger’s Pussy Galore.

For the second movie, 1963’s From Russia With Love, the budget was doubled, with locations that included Istanbul, Venice and Scotland. Many consider it the best Bond movie of all, an opinion shared by Connery and Craig. It had a sense of gritty realism we wouldn’t glimpse again until Craig smacked the franchise back down to earth in 2006 with Casino Royale. Bond’s brutal fight scene with blond Euro-thug Red Grant in a cramped train compartment on the Orient Express remains a masterpiece of hand-to-hand combat. It took three weeks to film and was performed mostly without stunt doubles. (Fights on trains would become a staple of the franchise, with Roger Moore battling a goon with a mechanical claw in Live and Let Die and one with steel teeth in The Spy Who Loved Me.) The movie’s climactic helicopter chase was as dangerous as it looked. An inexperienced pilot flew perilously close to Connery, almost taking his head off, and another chopper, carrying director Terence Young, crashed over water. Young finished the day’s shoot with his arm in a sling.

As the Cold War heated up, both Dr. No and From Russia With Love neutered the political resonance of Fleming’s fiction by changing the enemy from SMERSH, the Soviet spy agency in the books, to SPECTRE, the private criminal empire run by Ernst Stavro Blofeld, which Fleming didn’t create until Thunderball, the eighth novel. In Bond’s universe, reality is not permitted to disrupt fantasy. The only political frontier of strategic importance is the edge of the towel covering Bond’s butt on the massage table. Even in From Russia With Love, the authentic detail of its locations was undercut by casting. Bond’s Turkish cohort was played by Pedro Armendáriz, a Mexican veteran of John Ford westerns, who could not mask his accent. Neither could John Kitzmiller, the African-American actor who portrayed Bond’s Caribbean sidekick in Dr. No.

From Russia With Love introduced some classic Bond tropes. Welsh actor Desmond Llewelyn made his debut as Q, the MI6 weapons expert who would outfit 007 with gadgets in 17 films. Bond may have been frozen in the 1950s as a male model of conspicuous consumption, but no man is complete without state-of-the-art toys. Q began modestly, giving James a trick attaché case armed with a canister of tear gas. SPECTRE had its own, more sinister devices, such as Red Grant’s wristwatch garrote and Rosa Klebb’s poisoned toe spikes. For luxury spy gear, however, the pièce de résistance was Bond’s Bentley convertible equipped with . . . a large car phone. What’s wonderful about space-age gadgets is how quickly they become absurd artifacts of vintage futurism. As the spy-toy arms race escalated, by 1965 Thunderball had Bond soaring over London with a jetpack strapped to his back. (By 1973’s Live and Let Die, Q was dropped entirely because Broccoli felt the gadgets were getting out of control, but he was brought back by popular demand.)

Beginning every film with a pre-title action sequence was another tradition introduced by From Russia With Love. Over the years, as the action preludes got more extravagant and the titles became more slinky and seductive, whenever a Bond film failed to live up to the hype, it was often said its best moments were over by the end of the opening credits.

With Goldfinger (1964), those credits were accompanied for the first time by a title song, the legendary anthem belted out by Shirley Bassey. She recorded it while watching the credits roll, and as they kept running she held the final note until she almost passed out. The song was a massive hit and so was the picture, which became the fastest-grossing movie of all time until then. Goldfinger introduced Bond’s finest car, the Silver Birch Aston Martin DB5. With the car, the song and the gold-plated poster girl, 007 attained an apotheosis of pop-culture cool that he would never reach again. Fleming, who died shortly before the film’s release, would never see it.

Goldfinger introduced director Guy Hamilton, who brought a more comic touch to the franchise, and went on to shoot three more Bond films: Diamonds Are Forever (1971), Live and Let Die (1973) and The Man With the Golden Gun (1974). It’s also the only film from the Connery era that does not feature SPECTRE. And unlike most Bond movies, this is one movie that doesn’t incorporate a glamorous travelogue, aside from a sojourn in Switzerland. Much of it takes place in the United States, where Auric Goldfinger (Gert Fröbe) plots to infiltrate Fort Knox, but the U.S. scenes were shot in Britain. In Fleming’s novel, Goldfinger plots to steal the gold, but in the movie he tries to contaminate it with a dirty bomb, to goose the gold standard—foreshadowing the monetary terrorism of 2006’s Casino Royale.

Bond villains are often upstaged by henchmen, and that was the case with Goldfinger’s mute thug, Oddjob—played by Olympic wrestler and weightlifter Harold Sakata—who used his bowler hat as a lethal Frisbee. The filmmakers tried to cast Orson Welles as Goldfinger, but wouldn’t meet his price. Lowering their sights, they ended up with Fröbe, who spoke little English, delivered his lines in German and was dubbed by another actor. Having been a pre-war member of the Nazi party, Fröbe became nervous about a scene where his character unleashed nerve gas. In fact, Goldfinger was banned in Israel, then released after it was revealed that Fröbe had risked his life to hide Jews from the Gestapo.

In the Bond business, there’s no greater buzzkill than the real world, which is why SPECTRE was the perfect enemy. Before al-Qaeda, no one took the real-life spectre of a global terrorist conspiracy seriously. Although the plots of Bond films are routinely wired with doomsday scenarios of nuclear missiles being sunk, stolen, deflected and misdirected, that was just the sideshow. Viewers embraced Bond movies as vicarious tourism, a chance to join James in a cinematic Club Med. And, alpine ski jaunts notwithstanding, his destination of choice has always been the sea, from the Côte d’Azur to the Caribbean. Fleming, after all, wrote the novels beside a Jamaican beach.

Thunderball (1965) is the most aquatic of the movies. Shot in and around the turquoise waters of the Bahamas, with enough underwater scenes to turn the screen into a glass-bottomed boat, it sold more tickets than any other movie in the series. By then, it was clear Bond was selling a lifestyle and pioneering a kind of product placement that is now ubiquitous. Stocked with luxury brands, from Rolex to Revlon, Aston Martin to Calvin Klein, the Bond film became Hollywood’s answer to the glossy fashion magazine. The man who wore the watch, drove the car and filled the well-tailored suit was as much a model as an actor. And for Connery, the role had begun to wear thin. Even before shooting Thunderball, he admitted: “My only grumble about the Bond films is that they don’t tax one as an actor. All one needs is the constitution of a rugby player to get through 18 weeks of swimming, slugging and necking . . . I’d like to see someone else tackle Bond.” He swore the next movie would be his last, but shot three more.

You Only Live Twice (1967) was the first Bond film to almost completely discard the Fleming novel. Ironically, the screenplay was written by the author’s close friend, celebrated children’s author Roald Dahl, a novice screenwriter who called it “Ian Fleming’s worst book.” By the time the producers were shooting the movie, set largely in Japan, they were already seeking a replacement for their disenchanted star.

George Lazenby, Connery’s successor, signed on for seven movies but quit the role after just one, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969). Adapted from Fleming’s 10th novel, it’s a curious anomaly in the catalogue. Tricked out in a ridiculous wardrobe of ruffled shirts, a beige leisure suit, a cravat and a kilt, Lazenby came across as a bored action mannequin going through the motions. This is the movie where Bond gets married, with tragic consequences, to a contessa played with sly complexity by Diana Rigg, the only Bond girl ever to possess more authority and depth than Bond. While Rigg acted circles around Lazenby, a miscast Telly Savalas blundered through a gloating parody of Blofeld. Bond is upstaged at every turn—by a Fellini-esque cult of mind-controlled beauties in an Alpine chalet; a ski chase that’s buried in an avalanche; and an ailing Louis Armstrong crooning We Have All the Time in the World. And Lazenby served as proof that, without an actor to brand the role with his own personality, Bond is an empty shell. Timothy Dalton, the other “temp” Bond, was a far better actor, and darkened 007 with some gravitas. But Dalton never seemed to own the character, or convey the required relish for decadent pleasure. Liking the job is part of the mission.

READ: Why that mushroom lamp took over your TikTok feed—and your living room

Connery was talked into making one last picture for the Eon franchise, Diamonds Are Forever (1971). “I was really bribed back into it,” said the actor, who was paid a record salary of US$1.25 million (nearly US$8 million in 2020 dollars), plus 12.5 per cent of the gross. Like Elvis, Connery’s swan song ended in a Vegas setting, driving a silly lunar rover in a slapstick chase scene through the desert. Quite the comedown from the Aston Martin.

to space (Everett Collection)

After Connery turned down US$5 million to make Live and Let Die (1973), he gave his blessing to Roger Moore, who could not have been more different. Famous from TV’s The Saint, the 45-year-old Moore was soft-edged and elegant, with an air of rom-com affectation. Lacking the working-class grit of Connery or Craig, his Bond was more prone to snobbery than to cruelty. Moore made his Live and Let Die entrance as a flustered womanizer in a bedroom farce. After M surprised him at home with an early morning visit, he showed off his first gadget—a high-tech cappuccino machine. Serving coffee, and chasing after his boss with a sugar bowl, Bond is reduced to a servile secret service man. The next gadget is a magnetic Rolex that can divert a bullet, which he used to unzip the dress of a girl he has stashed in the closet.

Based on Fleming’s second novel, Live and Let Die cooks up a white gumbo of colonial blaxploitation, Mardi Gras and voodoo. Paul McCartney’s title song plays as the opening credits roll, and a montage shows a nude African woman in flames whose eyes bug out as her face turns into a skull. Filmed in Harlem, Louisiana and Jamaica (cast as a fictional Caribbean island), Live and Let Die brought Bond back to Jamaica for the first time since a tarantula shared his bed in Dr. No. The movie is crawling with snakes, crocodiles, sharks and retro clichés such as tying a white damsel to stakes in the jungle. You half expect a cannibal pot to materialize.

Moore considered The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) the best of his seven Bond movies. Directed by Alfie’s Lewis Gilbert, it’s the most spectacular, beginning from the pre-title scene of 007 flying off a mountaintop on skis and opening a Union Jack parachute—an uncut stunt filmed on Baffin Island’s Mount Asgard. The action, which involves a missing nuclear sub, ranges from Egypt’s pyramids to the ocean lair of a Captain Nemo-like villain, with Bond taking an underwater spin in an amphibious Lotus Esprit.

But during Moore’s tenure, as the franchise exhausted the Fleming oeuvre, the movies began to founder as they became bloated with techno spectacle and cynical self-parody. The cartoonish Moonraker (1979), which tried to capitalize on space operas like Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, was the last of Fleming’s novels to be adapted, and bore scant resemblance to the book. Like Connery, Moore began to talk of stepping down years before he eventually did.

For Your Eyes Only (1981), based on some of Fleming’s short stories, was the first Bond movie without M; Bernard Lee, who had played the pipe-smoking chief of MI6 in 11 films, died early in the shoot. Moore said it would be his swan song, then went on to make Octopussy in 1983, a year that saw a battle of the Bonds. The 52-year-old Connery was lured back by a rival production company to star in Never Say Never Again, another version of Fleming’s Thunderball, which had been tied up in years of legal wrangling over rights. It opened to generally favourable reviews and healthy revenues, although its box office failed to eclipse Octopussy, which had opened a few months earlier.

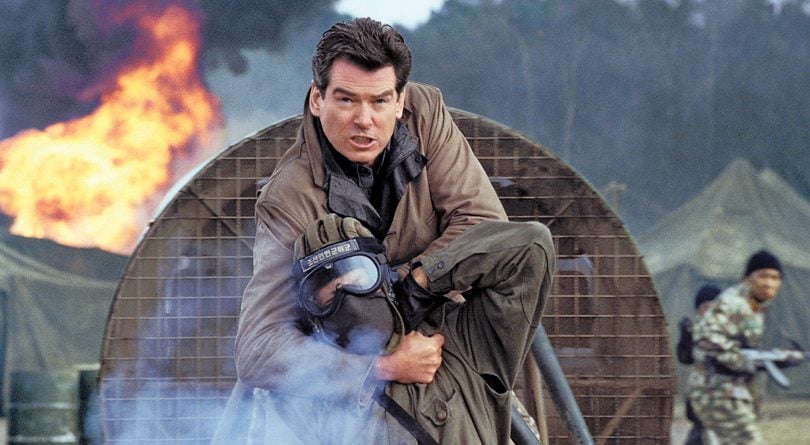

At 57, Moore took his final bow with A View to a Kill (1985), a movie he dissed almost as much as the critics did, admitting he had spent too long at the party. After the Timothy Dalton interlude of The Living Daylights (1987) and Licence to Kill (1989), contract disputes stalled the franchise for six years before another dashing TV star, Remington Steele’s Pierce Brosnan, finally kicked it back to life with GoldenEye.

Whenever a new 007 is minted, the first movie has to be an attention-getter. But by 1995, the new Bond was being launched into a movie culture of blockbuster spectacles enhanced by computer-generated imagery. The high-tech dream fetishized in Bond movies was taking over filmmaking itself. GoldenEye was the first Bond movie to use digital effects, yet physical stunts have always been a trademark staple. Directed by New Zealand’s Martin Campbell, the movie opened with a record-breaking bungee dive off Switzerland’s vast Verzasca Dam followed by a blazing firefight with a double-digit body count and a jump from a motorcycle to a plane in flight.

The story, the first not based on Fleming’s fiction, finds Bond in a changed world. The end of the Cold War is celebrated by a title sequence of silhouetted nudes hanging off giant hammers, sickles and toppled Soviet statuary. Taking over the role of M, a crisp and caustic Judi Dench informs 007 that he’s “a sexist, misogynist dinosaur, a relic of the Cold War.” Making M a matriarch and casting Dench was an inspired move. A superb actor with wit and gravitas, she is a walking time bomb in her own right, fused by a new polarity of sexual and global politics. Driving home the point that the world has changed, the climax has Bond bashing through St. Petersburg in a tank—on location in the city formerly known as Leningrad.

At the same time, GoldenEye milked nostalgia for the old Bond with a greatest-hits collection of classic scenarios: the Côte d’Azur casino, the Turkish bath, the bunker fortress, the doomsday countdown—and the silver Aston Martin, which Bond guns around the hairpin cliffs of Monte Carlo, doubling the clutch in pursuit of a woman in a red Ferrari who, as Fleming would say, “drives like a man.” But Xenia Onatopp (Famke Janssen) was not your father’s Bond girl; she crushed men with her thighs until they were gasping for air.

READ: The marvel behind Marvel Studios: How a group of B-list comic stars took over the world

Pierce Brosnan, stepping into the role at age 42, was a trim, economical 007 who kept his head down, wore the suits well, and made a virtue of neutrality and nuance. The Irish-born actor made for a less mannered Bond than Moore’s self-conscious thespian, who always looked most at home in a silk bathrobe, emanating noblesse oblige. But the smouldering Brosnan didn’t give off much attitude of any kind, which posed a problem. As the movies escalated in scale, they began to overwhelm his character, now orphaned both from Fleming’s fiction and his world. Dwarfed by fireballs and smothered in product placements, Bond was reduced to the obedient steward of a corporate franchise that had lost the plot. Brosnan was doing the job with executive precision, but didn’t look like he was having a whole lot of fun. And what could be more un-Bond-like than that?

Then Daniel Craig arrived as an unlikely saviour in 2006’s Casino Royale. He looked like a character actor, not a movie star. He had the face of a dock worker looking for a fight after the pubs had closed. And his casting ignited a firestorm among Bond fans. They said he was too blond, too brutish, not classically handsome. Craig, who took on the role at 38—the first Bond who hadn’t been born when the series started—didn’t just prove himself. He took violent possession of the character, and reminded us that the most glamorous action hero in the history of cinema was a polished thug. After 45 years, Casino Royale remade 007 from scratch. It resurrected Fleming’s first Bond novel, which had never been properly adapted, only plundered for a 1954 CBS episode about a CIA spy called “Jimmy” Bond, and the 1967 spoof with David Niven. Transposed to a post-9/11 era, the book became fodder for an origin story that rebooted both the character and the franchise.

With Martin Campbell back in the director’s chair, the producers turned to Oscar-winning Canadian Paul Haggis to write the script. When they approached him, “I thought they were out of their f–king minds,” Haggis said at the time. “Why would they want me? I thought I’d either reinvigorate this franchise or destroy it forever. So it’s a crapshoot. I approached it like everything else and asked questions of the protagonist. Like, what’s with Bond and women?”

Craig asked the same questions. Scuffing the polish off the icon to reveal an animal instinct, he portrayed Bond as a raw predator, a hothead whose feelings still ran dangerously close to the surface. He was a spy impersonating a playboy, but hadn’t taken the role to heart; his heart was still breakable. After 44 years, it was as if 007’s emotions were finally making their screen debut. Dench’s M came into her own as a severe matriarch. And as his minder Vesper Lynd, Eva Green was not just another duplicitous Bond girl, but a tragic love interest who got under his skin.

The violence in Casino Royale was more visceral than any Bond film before, beginning with the black-and-white prelude of James driving a man’s head into a bathroom sink. In an era of fast-cut digital chaos, the movie reminded us that nothing pumps up the adrenalin like spectacular stunt work unfolding in real time. The foot chase in Madagascar, featuring freerunner Sébastien Foucan, introduced Craig as an intensely athletic Bond; no lazing around the spa for him. When he was tortured, it wasn’t with the slow tease of a laser beam burning a path to his groin, as in Goldfinger. Stripped naked and tied to a chair, his genitals are pounded with a knotted rope. Even the plot has a sordid touch. The villain with a bleeding eye (Mads Mikkelsen) isn’t bent on world domination; he’s a seedy banker for terrorists trying to pay off a bad debt. And with serious actors like Mikkelsen, Dench and Craig given a licence to act, Casino Royale conveys at least the illusion of substance.

While subverting the Bond formula, the film took care not to destroy it, a fine line in a franchise that is as protective of its brand as Disney. Standards of nudity and profanity have changed radically in 50 years, but not in the Bond films. Take the scene in Casino Royale where Bond is asked if he wants his martini shaken or stirred, and responds, “Do I look like I give a damn?” With the film’s rating, “I could have said, ‘Do I look like I give a f–k?’ and we could have got it past the censors,” Craig said. “But it just didn’t feel right. It was profanity for profanity’s sake. The fact is, there’s no profanity in Bond.”

Craig’s second film, Quantum of Solace (2008), was less impressive. Directed by Marc Forster (Monster’s Ball), it was more of a flat-out action movie. Perhaps sated by Casino Royale’s marathon poker scenes, Bond doesn’t even set foot inside a casino; not once does he introduce himself as “Bond . . . James Bond.” The screenplay, co-written by Haggis, is a revenge drama with some barbs of wit, but no cheesy double entendres. The dialogue is sparse and the action hectic, with a fast-cutting style more typical of The Bourne Identity. Yet Craig conveys physical menace with the smallest gestures—flipping open a cellphone or grabbing a set of keys off a dresser.

MORE: Why Godzilla vs. Kong perfectly captures the tenor of our times

In 2012, after Craig co-starred with the Queen in a 007 stunt for the opening of London’s Olympics, came the royal flush of Skyfall, directed by Oscar-winning director Sam Mendes (American Beauty), who cast an echelon of Oscar-winning actors, including Javier Bardem, Ralph Fiennes, Albert Finney—and Judi Dench in an expanded role as M. It was Craig who hand-picked Mendes. “It’s a very showbizzy story,” he told Esquire. “I was at Hugh Jackman’s house in New York. It was a soiree, and Sam was there. I’d had a few too many drinks and I went, ‘How do you fancy directing a Bond?’ And he kind of went, ‘Yeah!’ And it snowballed from there.”

Mendes also recruited ace cinematographer Roger Deakins (who in 2017 would win his first Oscar for Blade Runner 2049 after 13 nominations). All Bond movies revel in eye candy, but none has been so profoundly gorgeous as Skyfall, which unfolds as a suite of moody compositions, from liquid neon vistas of Shanghai to the moors of Scotland. The plot involves a disastrous mission in Istanbul, after which Bond goes missing and is presumed dead, while the identities of MI6 spies are leaked on the internet. When Bond resurfaces, his loyalty to M is challenged with secrets from her past, and her tragic death seals the story with a surge of high tragedy that goes far beyond the Bond formula. As for Craig, the way he described his character, he could be talking about Hamlet—suffering from a “combination of lassitude, boredom, depression [and] difficulty with what he’s chosen to do for a living.” The actor, however, finally settles into his career choice as if to the manor born.

With Skyfall, we may have reached Peak Bond, with an Oscar-winning title song by Adele crowning the occasion. Three years later, Spectre slipped back into formula with bouts of cartoonish extravagance, but under Mendes’ direction, the level of artistry and acting remained high. In a magisterial opening sequence, Bond leaps across the rooftops of Mexico City, while a Day of the Dead parade fills the streets below, with Craig displaying breathtaking agility in buttoned suit and tie that somehow never get dishevelled. And an epic fistfight in a railway car—the one that earned him his knee surgery—is brutally convincing.

But the film’s most luxurious moments are its character pieces—the slow seduction of Léa Seydoux, who parlays the sly enigma of Dr. Madeleine Swann from damsel in distress to femme fatale, and the slow boil of Fiennes, who deepens his role as the new M with a dramatic severity that never flinches for a second. He’s joined by yet another Oscar winner with a more cavalier style, Christoph Waltz, who’s cast as an evil mastermind plotting to overrun the world with an Orwellian surveillance system. With his usual appetite for comic mugging, he, well, waltzes through the movie as if the scenery has never tasted so good. His character is revealed to be a resurrection of the classic Bond villain Blofeld—the original Joker—in a cat’s cradle of a script that tries to tie a bow on Spectre’s tangled strands of franchise genealogy. As actors come and go, there’s obvious merit in stitching some narrative continuity from one movie to the next, if only to hold the Bond Universe together. But in the end, despite all the preposterous plotting and stunts, any good Bond film hangs from one thread: the guy who convinces us he’s 007.

MORE: Ryan Reynolds is the quasi-hero we can all tolerate right now

Every generation gets the Bond it deserves. Connery was the rogue who got away with murder in an age when sex was harmless, smoking was de rigueur and air travel was romantic, especially while smoking. Moore was Disco Bond, a suave cynic who escorted 007 into an ’80s wasteland where both movies and music were overproduced. Brosnan was Gentleman Bond, trying to keep his cool amid the rising din of blockbuster mayhem. Craig is Existential Bond, who channelled the frustration of tackling the role into the character. Each of his predecessors became trapped and typecast. But Craig, like Bond himself, was determined not to be held hostage.

Since James Bond first appeared on screen in Dr. No, he has notched his bedpost with countless kills and sexual conquests. Hardly a Love Me Do kind of guy, he’s the original unrepentant rock star, more in the vein of that other jet-set Lothario with a franchise of the same vintage, the Stones’ Mick Jagger. Forever on the road, Bond cruises the colonies and stays in the best hotels, burning through women and booze. Satisfaction eludes him. But unlike an aging rocker, 007 is always replaced by a newer model. And as long as the revenue rolls in, he’s not about to fade away any time soon.

This article appears in print in the Maclean’s James Bond special collector’s edition, with the headline, “Bond everlasting.”

This article appears in print in the Maclean’s James Bond special collector’s edition, with the headline, “Bond everlasting.”