Egoyan feels the wrath of Cannes with ‘The Captive’

The first of three Canadian films gets a chilly reception in Cannes

Share

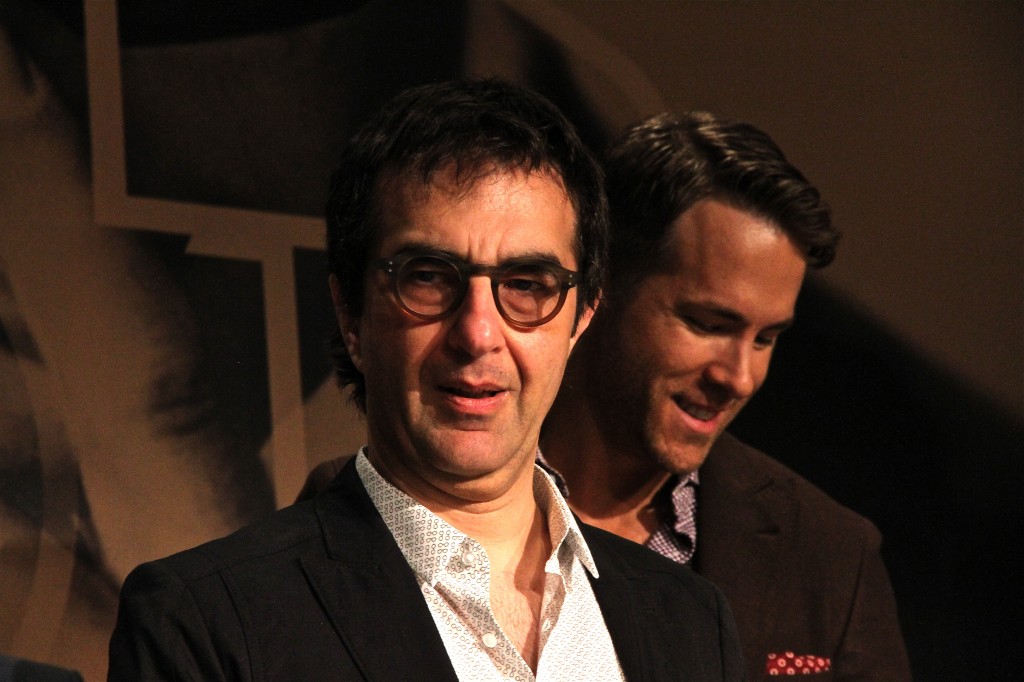

Being honoured on the high altar of Cannes is not always like dying and going to heaven. Sometime it’s just like dying. Atom Egoyan’s The Captive, the first of three Canadian among the 18 features selected for competition in Cannes, met with a brutal reception from the media crowd packed into this morning’s press screening at the 2,300-seat Grand Théâtre Lumière. The Captive—which stars Ryan Reynolds as the father of a kidnapped girl who resurfaces nine years later working with the pedophile ring that abducted her—was greeted with boos, soon followed by a volley of blistering reviews.

Comparing it to a bad dream, the Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw, his pen still dripping blood from his attack on Grace of Monaco, wrote that “line by line, scene by scene, [the film] is offensively preposterous and crass.” Variety‘s Justin Chang, called it “a ludicrous abduction thriller that finds a once-great filmmaker slipping into previously unentered realms of self-parody.”

I, too, was sadly uncaptivated by The Captive, which recycles Egoyan’s lifelong tropes and obsessions—abuse, bereavement, constructed identity, sinister surveillance—yet plays as a strangely generic genre film, lacking the emotional heft and spooky signature that usually make you at least feel you’re in an Egoyan movie, whether you like it or not.

The problem seems to lie in the fact the film has the trappings of an arty conceptual puzzle, of a kind that Egoyan is famous for, while straining to conform to the grammar of a conventional thriller. The result fails to satisfy either ambition. Most telling is that the score, by the director’s usually nuanced composer, Mychael Danna, goes out of its way to goose the dramatic tension at every turn. There’s even a climactic car chase, which seems wildly out of character for Egoyan. The last vehicle he sent off a snowy road was the schoolbus full of children in The Sweet Hereafter. To be fair, at least The Captive‘s car chase throws a distinctive Canadian kink into the formula: instead of crashing and burning, the vehicles just plow into soft snowbanks, as if this is the country with built-in airbags.

After a string of flops, the 53-year-old Egoyan is badly in need of a hit. The Captive, his 14th feature, has prompted a number of critics to wonder if his film career had slid into an irreversible decline. Although cinema is not sports, when Canadian film critics come to Cannes, most of us are at least secretly rooting for our directors. But if the film sucks, while we may not pan it with the cruel relish of our foreign counterparts, there’s no way to soften the blow. For a filmmaker like Egoyan, premiering a film in the Cannes Palais is like throwing all your savings onto a blackjack table at the nearby casino. If you win, you win big. But when you lose in Cannes, the spotlight can become unbearably hot.

My feeling, and that of many colleagues I talked to today, is that Cannes had no business leading The Captive to slaughter in the main competition in the first place. The festival tends to be super conservative in staying loyal to the auteurs who have made their career here. But Egoyan’s new film is clearly miscast on that lofty altar, and the festival’s programmers did everyone—especially Egoyan—a gross disservice by placing it there.The way things work here, after a film like The Captive is shown to the press at 8:30 a.m., the die is cast. That press screening is immediately followed by a press conference for the film. By the time Egoyan and his cast showed up, the film was already buried by an avalanche of hostile tweets. The filmmakers are kept in a bubble and protected as best as possible, so they can at least enjoy their evening red-carpet premiere before finding out that the knives are out. But in the age of social media that’s almost impossible. Before the premiere, at a cocktail on the beach hosted by TIFF and the Ontario Media Development Corp., negative buzz about the film was rippling through the crowd.

Though some critics may take pleasure in cruelty,as the critics piled on during the day, I began to feel sick about the whole business. So I deleted the instant tweet that I’d sent moments after the screening. Not that I’d revised my negative opinion of the film. But I realized there it’s almost pathological the way critical consensus now congeals so instantly after a screening, undercutting any kind of real discourse, as if it were just another metric, like a box-office gross. By engaging in social media so voraciously, film critics may in fact be sabotaging the already fraying future of their own profession.