The best of TIFF: 28 films, one festival

Film critic Brian. D. Johnson on his favourites of the fest

12 Years a Slave

Share

The feeding frenzy is finally over. During the festival, I chose to post mini-reviews only of the films I loved, or liked. Even then, it was hard to keep up. I tended to see the more high-profile pictures, those with stars and distribution, and TIFF 2013 produced an exceptional vintage. Unfortunately, a front-loaded schedule of must-see movies made it impossible to cover the waterfront. There are many titles I was sad to miss, including Philomena, The Unknown Known, Finding Vivian Maier, The Wind Rises—and more than a few Canadian titles. Plus, I’m sure, a bunch of amazing films I didn’t even know I’d missed. But here’s the best of what I saw, 28 films in all:

It’s based on the remarkable memoir of Solomon Northup, a free black man, and a skilled carpenter and fiddler, who was lured from Sarasota, N.Y., to Washington, D.C. by a pair of circus promotors in 1841, then drugged, kidnapped and sold into slavery in New Orleans. After the cartoonish pulp of Quentin Tarantino’s exhilarating revenge fantasy, Django Unchained, Steve McQueen’s epic is sobering to say the least. Played with simmering yet titanic force by Chiwetel Ejiofor, Northup is no Django-like action hero. He is a literate, sophisticated man who struggles to defend his dignity as it is assaulted , diminished and ground into the dirt. The movie’s most horrific scene, the one that will be talked about fearfully, involves a gruesome flogging that he is forced to administer to another slave, a young woman.

McQueen has marshaled a strong cast. Benedict Cumberbatch has a smallish role as the plantation boss who first purchases him at auction. Although he has no compunction about separating a slave woman from her children, this slave owner is a relatively gentle man compared to his next owner, an alcoholic sadist (Michael Fassbender) who runs a cotton plantation. Yet Fassbender makes this monster utterly credible. Producer Brad Pitt, meanwhile, plays a white knight, a Canadian carpenter who eventually comes to Northup’s rescue. But his role is modest. This is not a Brad Pitt movie, or a story of a white guy saving a slave. It belongs to Chiwetel and the remarkable ensemble portraying his fellow slaves. With McQueen, they’ve created a landmark picture of devastating power.

The Square

Director Jehane Noujaim (Control Room), who was raised in Cairo and educated in Harvard, demonstrates how the long arc of single documentary can convey depths of drama and understanding that elude countless hours of fragmented CNN coverage. Her film spans over two years of protest in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, from the euphoric occupations that brought down the 30-year regime of President Hosni Mubarak to last summer’s overthrow of President Mohamed Morsi. (After the documentary was premiered as a work in progress at Sundance, where it won the Audience Award, the filmmakers returned to the fray to catch up with history.) This is no guerrilla doc cobbled together from cellphone footage. Beautifully shot and edited, it plays like an epic drama, encompassing a vast canvas of protest while tracking the personal narratives of several key characters. They include Ahmed, a charismatic young militant; Magdy, a congenial member of the Muslim Brotherhood; and Khalid Abdalla, an eloquent actor who starred in The Kite Runner. No revolution has ever been filmed from the inside with such intimate detail and breathtaking scope. The footage is at times horrific and heartbreaking. Throughout the upheavals, Egypt’s military emerges as a brutal, intransigent barrier on the road to democracy. The film also shows how the Muslim Brotherhood collaborated with it to betray the movement. Watching The Square, it was hard not to worry about the plight of those two Canadians who have been languishing in a Cairo jail since August 16, filmmaker John Greyson and physician Tarek Loubani. And the campaign to free them—supported by a proliferation of “#FREEJOHNANDTAREK” buttons at TIFF—took on a new urgency.

This 3D space thriller about NASA astronauts who face a calamity while repairing a space station is quite unlike anything we’ve seen before. Sandra Bullock–who is supported by George Clooney but spends much of the movie alone—gives a bravura performance that raises the bar for the female action hero and sends it spinning into a whole new orbit. I tend to avoid the word “awesome” but in the case of Gravity, it’s oddly precise. Directed by Alfonso Cuarón (Children of Men), it invents its own formula, and cranks adrenaline to untold heights, achieving moments of transcendence and beauty reminiscent of 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Tree of Life. It literally takes your breath away, yet it’s a triumph of weightless entertainment sans gravitas. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. Escape doesn’t get much better.

Prisoners

This intense thriller is one of two TIFF entries that mark Denis Villeneuve’s double-barrelled English language debut—both starring Jake Gyllenhaal. The other is Enemy. While Enemy is a small Canadian film set in the existential wastelands of Toronto and Mississauga, Prisoners is a studio picture set in America’s heartland. It arrives at TIFF on a wave of positive momentum from the Venice festival. And it catapults Quebec’s hottest auteur into the major league of Hollywood directors. It’s an exceptionally dark and harrowing story about the abduction of two young girls—a grisly suspense picture that verges on horror. Gyllenhaal gives the performance of his career as a laconic, tight-wound police detective trying to crack the case; the same can be said of Hugh Jackman, who is scarily explosive as a father who abducts a mentally handicapped man initially linked to his daughter’s disappearance (Paul Dano). We are deep in David Fincher territory. As a genre clinician, Villeneuve shows he’s in Fincher’s class, yet achieves a more profound level of intimacy and gravitas. As a diabolical genre piece, his film recalls Silence of the Lambs and Fincher’s Zodiac. But its stark, wintry compositions also remind us that this is the director who dramatized the Montreal massacre in Polytechnique (2009). Occasionally I got lost in the labyrinthine plot twists, but at almost two-and-a-half hours there’s not an ounce of fat on its gripping narrative. From the opening scene of hunting venison for Thanksgiving—an grim echo of The Deerhunter set to the Lord’s Prayer—it begins a procedural descent into an American darkness of unquestioning faith and almost biblical violence. And if there’s any justice in that America, Villeneuve, who was Oscar-nominated for Incendies, should see his film score in major categories. A nomination for Jackman at least seems inevitable.

Dallas Buyers Club

This is a banner year for Quebec filmmakers, although its two most prominent auteurs have scored triumphs as directors of Hollywood movies—first Denis Villeneuve with Prisoners, now Jean-Marc Vallée with Dallas Buyers Club. Matthew McConaughey turns in funny, moving and downright virtuosic performance in the real-life role of Ron Woodroof, an electrician and rodeo cowboy who comports himself as a brash, boozing, inexhaustible womanizer until he is stricken by HIV, apparently contracted from closeted bisexual encounters. At first he is in denial, then he’s chasing black-market doses of AZT with beer and cocaine, all the while bragging he’s no “faggot.” But with a doctor’s forecast that he has just a month to live, Woodroof begins to fight his disease like a stubborn bull-rider. He sets himself up as a one-man drug cartel, importing large batches of unapproved medicine from Mexico, and sets up a “buyers club” to help those afflicted with AIDS. Allying with an ailing drag queen (a dazzling Jared Leto), this cowboy-booted gay basher becomes the gay community’s best friend, and a passionate crusader against Big Pharma and FDA. After showing his brilliance with movies that never broke out of the art house—C.R.A.Z.Y, The Young Victoria and Café de Flore, Vallée will finally get the recognition his deserves with this flamboyant yet well-grounded tour de force. I hate to again use the “O” word, but an nomination for McConaughey seems very likely.

The F Word

Romantic comedy is genre that has eluded Canadian filmmakers, who tend to skirt around the requisite formula rather than embrace it, like musicians refusing to play a straight-ahead pop song. But finally here’s a Canadian movie that nails the romcom. With The F Word director Michael Dowse (Fubar II, Goon) shows how its done in a film that almost flaunts its contrivances. Wallace (Daniel Radcliffe) and Chantry (Zoe Kazan) meet cute in a blaze of witty banter. He’s a chronically single med-school dropout and she’s an animator with a steady boyfriend, a humorless U.N. copyright law negotiator. They spend most of the movie in that vintage Woody Allen limbo of best friends in romantic denial, while Chandra’s sister (Megan Park) and Wallace’s pal (Adam Driver) provoke from the sidelines. Revealing its provenance as a play, the glib dialogue is too clever by half. But its richly entertaining. The performances and the direction are sharp. And despite the fact that the cast is largely non-Canadian, Michael Dowse has made a movie that at least looks Canadian, in a good way. Shooting the hell of Toronto, he’s composed a sexy, yet authentic valentine to the city, framing it as a lakefront paradise. Sure, Atom Egoyan and Sarah Polley made it glow in Chloe and Take This Waltz respectively. But from the Beaches boardwalk to Riverdale Park, Dowse makes it look cool, as a place where people might actually want to live. Radcliffe and Kazan even go skinny dipping in the lake under the moonlight. And you can’t fake that.

Tracks

Mia Wasikowska gives a bravura performance in John Curran’s adaptation of Robyn Davidson’s famous memoir, chronicling her epic trek across the Australian desert. In 1977, Davidson embarked on a 2,700-km journey from Alice Springs to the Indian Ocean, accompanied by four camels and her dog. When you think Australia, you think kangaroos, but the country is rife with feral camels. There’s as much sand in this movie as in Lawrence of Arabia, but here these strange beasts with scary teeth finally get their close-up. American director John Curran captures the animals, landscape, and his dusty heroine with an authentic eye, conveying the epic hardship of Davidson’s odyssey. Providing some comic relief along the way, there’s an abrasive romance that reverses the usual “this is no place for a woman” trope—to obtain funding from National Geographic, Davidson reluctantly allows an annoying photographer in a Land Rover (Adam Driver) to intercept her every month. And in case we’re wondering if Wasikowska is too pretty to be the kind of girl who would ever undergo such a trek, the movie ends with a photo montage that shows the real Robyn Davidson looked like more a movie star that she does.

The Lunchbox

In this modest yet beguiling feature debut by Mumbai writer-director Ritesh Batra, a misdirected lunchbox becomes a vehicle for an epistolary romance. Ila (Nimrat Kaur), a neglected middle-class housewife, tries to spice her her marriage by taking special care with the lunch she prepares each day for her distracted husband. The delivery ritual alone is something to behold. Each day in Mumbai, some 5,000 lunchbox couriers deliver hot meals in modular canisters to workers around the city. But Ira’s payload keeps ending up in the wrong hands, landing at the desk of a moody widower named Saajan (Irrfan Khan), an insurance claims accountant who is about to retire. Saajan is seduced by the food, and begins exchanging letters with Ira, which are ferried back and forth in the lunchbox. Khan, a Bollywood star best known to the West for Slumdog Millionaire and Life of Pi, is a droll, quietly charismatic presence, conveying as much in moments of reflection as with dialogue. Though the narrative unfolds as a minimalist fugue, the film beautifully shot, a lavish slice of life a city thick with trains and traffic and star-crossed destinies.

Enemy

This is the “other” Denis Villeneuve film at TIFF. Overshadowed by Prisoners, his Hollywood debut, it’s a Canadian art house curiosity, yet it too stars Jake Gyllenhaal. And just when you thought English Canadian cinema could not get any more weird, Villeneuve has upped the ante, like a provocateur breezing in from Montreal to peel back the dark underbelly of Toronto. He’s composed a perverse existential puzzle that conforms to the canon shaped by Cronenberg and Egoyan as if to the manor born. Based on the novel The Double by Nobel Prize-winning author José Saramago, Enemy is a psycho-sexual thriller about Adam, a university lecturer who discovers he has an exact double named Anthony, a minor actor with a secret life. Gyllenhaal plays both men, who are a study in opposites. Adam is a shy, sensitive soul who lives in a barren low-rent Toronto high-rise and has distracted sex with a blond girlfriend (Melanie Laurent). Anthony is a brash philanderer with a secret life who lives with a blond, very pregnant wife (Sarah Gadon)—their home is a luxurious Mississauga condo, one of those curvy showpieces. With a grim palate that swings from grey to smog-yellow, the camera dotes on condos, office towers and freeways, a forbidding haze of concrete. If The F Word makes Toronto look warmly liveable, the city has never looked more austere than in Enemy, not even in Cronenberg’s Crash. Villeneuve’s portrait of urban angst is a creepy essay about identity, anonymity and the horror of not knowing the man who shares your bed. Its glacial narrative, which stops cold with a baffling twist at the end, is not what you’d call user-friendly. But between the Two Jakes and their two solitudes, Villeneuve creates a delicious tension—a sense of latent menace that casts a narcotic spell.

Enough Said

In one of his last performances before his death, Sopranos legend James Gandolfini co-stars with Julia Louis-Dreyfuss in an astute, funny and tender romantic comedy written and directed by Nicole Holofcener (Lovely and Amazing, Please Give). They play Albert and Eva, divorced parents who strike up an unlikely courtship as both are about to send their daughters off to college. They have curious professions: Eva is a mobile massage therapist who lugs her table around town, and Albert is a television archivist with an encyclopedic grasp of trivia from the early days of TV. Both Gandolfini and Dreyfuss, of course, are TV icons, but they succeed in creating rich, down-to-earth characters who become utterly convincing in their own right. However, so much is made of the fact that Albert is an obese slob, a heart attack waiting to happen, that it’s impossible not to be reminded of Gandolfini’s sad fate. Holofcener, whose directing credits include Sex and the City and Parks and Recreation, displays no visual flair. It’s a bit like watching TV—but the best kind of TV, with well-developed characters, smart yet believable dialogue, and a deep emotional resonance.

Gabrielle

Like the title character she plays, Gabrielle Marion-Rivard has a mental disability called Williams syndrome, whose sufferers often possess musical talent and perfect pitch. This tender coming-of-age story is the tale of Gabrielle and Martin (Alexandre Landry), disabled young adults who fall in love while rehearsing in a Montreal choir for the disabled. Gabrielle, who lives under the care of her sister (Mélissa Désormeaux-Pouli) is desperate for independence, while Martin sees his romance with her thwarted by his over-protective mother. The film is directed by Louise Archambault, who won TIFF best first feature prize with Familia (2005), and produced by the team behind Quebec Oscar nominees Incendies and Monsieur Lazhar. And it may well be Canada’s official submission to the Academy’s foreign language category this year. Marion-Rivard is radiant in the lead role, and Archambault combines a poetic eye with a documentary grip of authenticity. The choir in the film, Les Muses, is a real-life organization offering professional training in song, dance, and theatre, to those with intellectual disabilities, developmental disorders and physical and sensory challenges. The story’s hook is a concert they will play with legendary singer Robert Charlebois. When members of the the choir trade verses of his poignant ballad ‘Ordinaire’ (Je suis un gars bien ordinaire…”), it has never had such heart-breaking resonance.

The Fifth Estate

It’s a more inspired choice that usual for TIFF’s opening night gala—a breathless thriller that treats the speed of data as a matter of life and death. Directed by Oscar-winning filmmaker Bill Condon (Kinsey, Dreamgirls), this propulsive drama does for Julian Assange what The Social Network did for Facebook mogul Mark Zuckerberg. It portrays him as a visionary who is pathologically insensitive, a genius with a cruel wit whose single-minded ambition leads him to betray his partners and his sources. But unlike Zuckerberg, who seems to have no higher goal in life that personal power, Assange comes across as a genuine revolutionary with a mission that unfolds like a sub-atomic particle accelerator. A cyber hybrid of hero and villain. Like his long-suffering accomplice, Daniel Domscheit-Berg (Daniel Brühl), we can’t help but get caught up in his vortex, especially when the actor is Benedict Cumberbatch, who so on fire these days you wonder if he’s human. Check out my recent interview with director Bill Condon for the magazine.

Blue is the Warmest Colour (La Vie d’Adele)

The image of the French movie as an erotic frontier—where art, sex and romance freely commingle—gets un deuxieme souffle in the Palme D’Or winner from Cannes. It’s a lesbian love story about a 17-year-old schoolgirl who comes of age by falling for an older artist. Powered by exceptional performances from Léa Seydoux and Adèle Exarchopoulos, this intimate three-hour epic unfolds in graphic detail, sexual and emotional; it goes where mainstream cinema has not gone before. With all the sex, the cigarettes and discussions of Sartre, there could not be a more archetypical French film, yet it busts through cliché into uncharted realms of intensity. Since the film premiered in Cannes, Seydoux and Exarchopoulos have cracked the publicity bubble, and contradicted the merry image of filmmaking harmony that they conveyed before the world’s press. Now they says the shoot was arduous and their director was tyrannical. But that doesn’t diminish their performances, or the film.

The Past

Shot in Paris by Oscar-winning Iranian director Asghar Farhadi (A Separation), a tale of divorce unfolds as an onion-skin riddle of secrets and lies. It’s torqued with enough revelations that it would be melodrama if it were not so exquisitely rendered. Argentine-born French actress Bérénice Bejo (The Artist) won the actress prize in Cannes for her tempestuous turn as a Parisian mother separating from her Iranian husband.

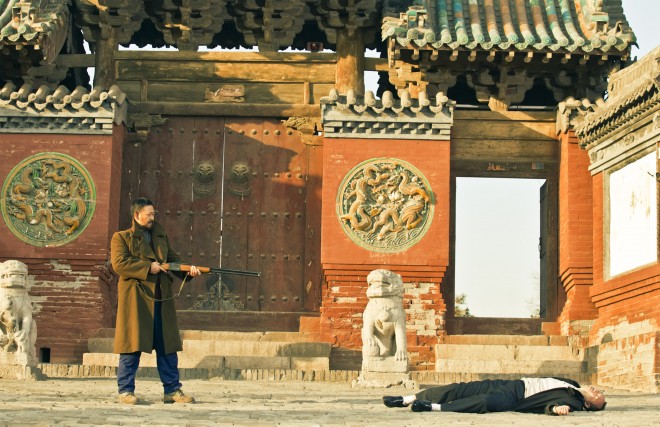

A Touch of Sin

Against panoramic vistas, China’s Jia Zhangke directs a suite of four stories splattered with vigilante gun violence, not all of it reprehensible. A kind of Chinese Pulp Fiction, it adds up to a powerful portrait of desperate individuals driven to extremes in a context of official corruption and runaway commercial development. They range from a mine worker who picks up a shotgun to get even with a super-rich boss to a massage attendant (Jia’s wife and longtime leading Zhao Tao) who wreaks bloody vengeance against a sexual predator. As a contemporary revision of the W?xiá genre, these ultra-violent tales of explosive retribution are set against gorgeous landscapes in various far-flung corners of China. What’s remarkable is that Jia partly based his stories on sensational real-life crimes that were well-known from the country’s newspapers. They add up such a massive critique of China’s new Cultural Revolution—the decadence of unbridled state capitalism—that it’s surprising government censors have allowed the film to reach the screen.

The Invisible Woman

Ralph Fiennes directing himself as Charles Dickens? Everyone needs a challenge. It’s a bit hard to find the actor behind the beard, but this is a fascinating intrigue that reveals the little-known story of the novelist’s slow-burn secret affair with a young fan, actress Nelly Ternan (Felicity Jones). Fiennes shows that his bold directorial debut, Coriolanus, was no fluke. And once again he’s made the kind of movie that you feel no one else would dare attempt. Scripted by Abi Morgan (The Iron Lady, Shame), this period piece is layered with a subtle intelligence. Despite the fact that Fiennes is all over it as director and star, the film is so devoted to its heroine Jane Campion could have made it. But what’s most audacious are the long silences that pervade the drama: a true luxury in a multiplex culture intent on deafening the viewer.

The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby: Him and Her

This audacious debut feature from American filmmaker Ned Benson splits the narrative in two. Set in New York City, the story unfolds as two distinct films that play back to back—one from the husband’s viewpoint, the other from the wife’s—as the couple undergoes a separation after tragic event has cast a pall over their marriage. Conor (James McEvoy) owns a failing bistro with a loser chef (Bill Hader), and lives in the shadow of his morose father (Ciarán Hinds), one New York’s most successful restaurant owners. Eleanor (Jessica Chastain), the daughter of a professor (William Hurt) and a college drop-out, re-enters academe by taking a course on Identity Theory and befriending its cynical prof (Viola Davis). Facing this three-hour marathon at 9 a.m. on the final Saturday of TIFF was perhaps ill-advised. It felt slow. But it was billed as a work in progress, and after being picked up by Harvey “Scissorhands” Weinstein, it may indeed be trimmed before release. Strong performances, however, sustain the drama. And the bold device of separate lives/separate movies, which creates a circular undertow of emotion, should stay in tact.

Watermark

As a follow-up to her award-winning documentary, Manufactured Landscapes, director Jennifer Baichwal does another dance with epic photographer Ed Burtynsky, but this time he’s elevated to co-director. Shot in stunning 5K digital video by Baichwal’s producer and partner, Nick De Pencier, this is a more ambitious picture on a larger canvas about a shrinking resource with an endless horizon. It’s a film about water, with a meandering narrative that’s as fluid and as expansive as its subject. The seas may be rising, but rivers are being choked and the water table is shrinking. Vistas range from the pristine gorges of B.C.’s Stikine River to hurtling explosions of brown water corralled by China’s mega dams, from masses of pilgrims bathing in the Ganges to eerie crop circles of aquaculture sucking dry America’s breadbasket. Watermark is a kind of mega hydro project of its own, generating waves of shock and awe.

Tim’s Vemeer

The stunning photo-realism of the paintings by Dutch master Johannes Vemeer have often made art historians wonder if he used technical wizardry to create them. Tim Genison, an American inventor of computer graphics equipment with money to burn, tries to prove that Vemeer in fact used an optical device. Genison, who is not an artist, creates such a device and sets out to reproduce Vemeer’s The Music Lesson, one tiny brushstroke at a time. He begins by building an exact studio replica of the room depicted by Vemeer in the painting. Genison drew inspiration from two books, Secret Knowledge by David Hockney and Vermeer’s Camera by Philip Steadman, and both authors appear in the film to check out his work. The documentary is directed with surprising finesse by Penn and Teller, the magic duo fond of exposing hoaxes. As filmmakers they are total pros, tracing Jenison’s mission with an eye for fastidious detail not unlike his own, yet framing it with their own wry perspective. The film is a fascinating inquiry, but over time it becomes even more intriguing as a Herzog-like portrait of one man’s crazy obsession, and just how far he will go to fulfill it.

Parkland

Peter Landesman directs a crack ensemble in a breathless re-enactment of what went down in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963—the day of John F. Kennedy’s assassination—and the events leading up to his funeral. The title refers to the Dallas hospital where a young surgical resident (Zac Efron) fights to save Kennedy’s life, then struggles to save his accused killer, Lee Harvey Oswald, two days later. As well as the surgeon, the film dwells on four other traumatized characters who are swept up in the action: Abraham Zapruder (Paul Giamatti), whose 8mm film becomes a historic document; Dallas Secret Service chief Forrest Sorrels (Billy Bob Thornton); James Hosty (Ron Livingston), an FBI agent investigating Oswald prior to the assassination; and Oswald’s estranged brother, Robert (James Badge Dale). Shot in a style of handheld verité, intercut with archival footage, this is gripping drama. The camera lingers too gratuitously on a weeping Jackie Kennedy. But otherwise the film finds its strength in the quintet of lesser known players, especially Zapruder and, oddly enough, Oswald’s stoic brother, who’s cast in a heroic, almost Kennedy-esque, light.

Like Father, Like Son

In Cannes, we were all speculating that jury president Steven Spielberg would warm to this this soul-searching tale of fatherhood, which ended up winning the third-place Jury Prize. And sure enough, Spielberg has just announced he will remake the movie in English. It’s hard to imagine how his mighty hand could improve upon Hirokazu Kore-Eda’s fine-tuned drama; just changing the cultural landscape would seem radical enough. Like Father, Like Son is the story of two families who are shocked to discover that their six-year boys were switched at birth. One family, headed by a workaholic architect, lives in an upscale Tokyo high-rise, the other above their appliance shop outside the city. As the families agree to maintain the status quo, and arrange mutual visits, the class differences between their values, and parenting styles, start to upset the symmetry of their civil arrangement. Each of the characters are sharply developed, but the narrative balance inevitably tips toward towards the emotionally challenged architect, deftly played by Japanese pop star Masahuru Fukuyama.

August: Osage County

Based on the Tony-winning stage hit by Pulitzer prize-winning playwright Tracy Letts, this story of a family meltdown offers the richest payload of powerhouse female performances we’re likely to see all year. Director John Wells doesn’t open up the play, so we feel we’re watching as voyeurs, from a safe distance. We are trapped in a house, and a hellish family, after the funeral of a grandfather who has committed suicide. As dark secrets are stripped away, Meryl Streep and Julia Roberts pull out all the stops in a vicious mother-daughter catfight that has viewers gasping in shock.There’s some fine work in supporting roles from Juliette Lewis, Chris Cooper and Julianne Nicholson, plus a weird turn from Benedict Cumberbatch. But Streep and Roberts are the main event. As a drug-addled cancer victim in a wig, Streep gives the showier performance, so desperate to entertain it’s almost vaudevillian. I found her mannerisms too detailed, her acting too visible. Roberts is the real surprise. Building up to a blue rage, her character bears down on Streep’s like a heat-seeking missile. It’s best work of her career. The question is: who will Harvey Weinstein submit as the Best Actress candidate for the Oscars? My vote would be Roberts, whose character overtakes Streep’s over the course of the film. Meryl will have a better chance in the supporting category.

Gloria

Paulina García won Berlin’s best actress prize, the Silver Bear, for her delightful performance in the title role. Gloria is a divorced Chilean woman in her late fifties who’s unwilling to give up on romance, or sex, and refuses to drift into domesticity as a grandmother. She spends her evenings at singles clubs, dancing the night away with an air of coquettish optimism, looking for a tolerable man despite the grim odds of finding one. Hope arrives in the form of Rodolfo (Sergio Hernández), who is smitten with her from the first dance, but the fact that he is so recently separated suggests this liaison will not be smooth. With his fourth feature, Chilean filmmaker Sebastián Lelio directs with a sensitive eye, and lets the narrative wrap seamlessly around García’s beguiling performance. Her wry, circumspect point of view infuses the whole film, as a woman ready to take her chances and surrender to passion, but not at the expense of her self-respect. Implicitly feminist, Gloria is portrait of a mature woman coming of age before it’s too late, and though it’s as modest and straightforward as its heroine, it’s exotic—a kind of film we haven’t seen before.

Belle

At a festival where audiences voted the gruelling 12 Years a Slave TIFF’s most popular film, here’s a period piece about slavery that is easier to watch. Belle is a sumptuous costume drama based on the true story of Dido Elizabeth Belle, an 18th-century heiress with a unique lineage: she’s the illegitimate, bi-racial daughter of a British Naval officer and an African slave. British actress Gugu Mbatha Raw (herself the mixed-race daughter of a black South African doctor and a white English nurse) navigates an agile line between fragility and boldness in the title role. Dido is caught between a rock and hard place: “How may I be too high in rank to dine with the servants but too low to dine with my family?” She’s an aristocratic lady with a large dowry, yet her race makes her an embarrassment to for any potential suitor of good “breeding.” On the other hand, her imperious uncle, Lord Mansfield (Tom Wilkinson), is appalled she would stoop to love a lowly vicar’s son who has caught her eye—Mansfield’s free-thinking legal apprentice (Sam Reid). In the role of Dido’s luminously blond cousin, Canada’s Sarah Gadon turns in a precision performance, and once again shows she’s utterly at home in a period film. Emily Watson and Miranda Richardson round out the cast. Belle‘s lavish visuals and smart dialogue are as finely tooled as in an A-list Jane Austen epic. But aside from the issue of a woman’s subjugation, the dramatic stakes are raised by a historic court case in which Lord Mansfield, the highest judge in the land, is ruling over a charge of fraud involving a slave ship that destroyed its diseased human cargo to cash in an insurance claim.

The Grand Seduction

This is as close as English Canadian cinema came to providing the festival with a populist crowd-pleaser. Don McKellar has directed a spirited remake of La grande séduction, Quebec director Ken Scott’s 2003 box-office hit. It’s a broad comedy about a tiny fishing village that tries to lure a doctor into setting up a practice so it can qualify for a new factory. The doctor (blockbuster refugee Taylor Kitsch) is a cricket fiend, so the community mounts a preposterous fiction in which everyone is mad for the game, with an improvised cricket pitch laid out on the rocks and the men flailing away in whites that the women have sewn out of drapes. That’s just the welcome party in an extended hoax. McKellar has relocated the setting from an island in the Gulf of St. Lawrence to a Newfoundland outport, and marshalled a Who’s Who of East Coast talent, including Gordon Pinsent, Mary Walsh, and Cathy Jones. Pinsent is wonderfully droll and disheveled. But the movie really belongs to Irish actor Brendan Gleeson (The Guard), who plays the mastermind of the fraud, and a bogus father figure to the naive doctor who taking him fishing—pulling a fish out of the sea that came from someone’s freezer. Kitsch never seems wholly convincing as the mark. And with Liane Balaban cast in an underwritten role as his love interest, the romance is half-baked—capped by whimsical ending taken from the original that feels tacked-on. But then The Grand Seduction is not really a romcom. It’s sweet farce in the Waking Ned Devine genre, the tale of a village making an idiot out of a city slicker—a narrative heist, so to speak. The movie may leave the audience feeling defrauded as well, but there are some good laughs along the way.

All Is By My Side

Andre Benjamin, one half of the American hip hop duo Outkast, does a remarkable job of incarnating the look, sound and attitude of music legend Jimi Hendrix. Making his feature directing debut, John Ridley (who wrote 12 Years a Slave) takes an oblique, understated approach to the Hendrix story, focussing on the early years leading up to his star-making appearance at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival. This is no bio-pic. But the singer’s emergence in the London blues scene is framed the affections of two women, the hard-headed Linda Keith (Imogen Poots), who is also the girlfriend of the Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards, and a less sophisticated admirer named Kathy Etchingham (Hayley Atwell). The filmmakers didn’t have the rights to any of the Hendrix compositions, but that doesn’t matter as much as you’d expect. Taking the non-Hollywood high road, Ridley succeeds in capturing the artist’s fluid rhythms, laconic style, and cosmic view of existence.

Can A Song Save Your Life?

The answer is yes, obviously. We’re talking about a crowd-pleaser that prompted Harvey Weinstein to fork over $7 million for distribution rights after the TIFF premiere. Can a Song Save Your Life? comes from Dublin-born director and musician John Carney, who made Once, the tiny musical romance that shot all the way to the Oscars, winning Best Original Song. You could call this movie is Twice, though it’s not a sequel, and far more than twice the scale of Carney’s previous effort—with Hollywood stars and a bigger band on board. Dan (Mark Ruffalo), a fallen record executive, discovers Greta (Keira Knightley), a singer-songwriter with more talent than ambition, and convinces her to record an album—live in the streets of Manhattan. Ruffalo tends to overplay his role as a garrulous music biz veteran, madly flipping between cynical and passionate. But Knightley is both charming and authentic, and has a way with a song. As the boyfriend who dumps her, Adam Levine (Maroon 5) delivers a lethal caricature of a narcissistic rock-star. And Hailee Steinfeld and Catherine Keener sweeten the cast as Dan’s estranged daughter and wife. The movie feels more contrived than Once, and the music is far more slickly produced than the premise pretends it is. But with Levine, Mos Def and CeeLo Green adding their chops, the picture makes good on its title.

Cannibal

This perversely tasteful tale of a serial killer involves a mild-mannered Spanish tailor in Granada. He kills beautiful women who have the misfortune to be attracted to him, takes them to a stone cottage nestled high in the mountains, butchers them on a marble slap and stows the plastic-wrapped human filets in his apartment fridge, which contains nothing else. It’s not a horror film; there’s barely a trickle of blood in the whole picture. It’s a movie that says: beware of the man never unbuttons his impeccable suit, and who tries to dissuade beautiful women from getting close. The fastidious killer (Antonio de la Torre) is nothing like Hannibal Lector. He’s a bespoke cannibal who dines alone with a glass of red, sawing a dispassionate steak knife through a shoal of pink meat. Not unlike the way he fondly handles the bolts of fine wool shelved in his immaculate shop. Women come to this killer unbidden; he’s a shy, silent chick magnet. The plot is a contrivance, involving the twin sister of a masseuse who has mysteriously disappeared (Olimpia Melinte). But with haunting visuals that range from mountain peaks to church rituals, Manuel Martín Cuenca casts an eerie spell, displaying a firm directorial hand that is as quietly assured as the killer’s.