Life at $20 a barrel: What the oil crash means for Canada

As the price of crude plunges, and drags the loonie with it, the pain stretches far beyond the Alberta oil patch. What’s next for Canada’s economy?

Oil Background. Matt Jeacock/Getty Images

Share

In September 2008, when thousands of riled-up Republicans filed into the Xcel Energy Center in Saint Paul, Minn., for the party’s national convention, the upcoming election wasn’t the only thing on their minds. Oil had soared to US$145 a barrel just months earlier, and though crude had begun to fall fast—a harbinger of the Great Recession—Americans fumed that they were still paying $4 a gallon at the pumps and the nation was gripped by anxiety over its reliance on the Middle East for its energy needs. So when party stalwart Michael Steele took the stage for his keynote address, he preached the bumper-sticker gospel of energy independence. “Drill, baby, drill!” he hollered. “Drill, baby, drill!” the multitudes roared back.

But away from the convention, a legion of energy companies were already doing just that, furiously exploring the oil fields of Texas, North Dakota, Colorado, and anywhere else they could park a rig. That drilling brought on the biggest energy revolution the world has seen in decades, one that continues to be measured in U.S. oil production at 40-year highs, glutted global crude inventories and a seemingly bottomless floor for oil prices. The price of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate crude, the benchmark measure for U.S. oil, fell more than 15 per cent last week, briefly dipping below US$30 on Tuesday, a 12-year low.

A growing number of grim forecasts are calling for even that demolished price to fall further. Last fall Goldman Sachs warned oil could hit US$25 as crude storage tanks reached capacity. In December a report from the International Monetary Fund argued new oil flowing from Iran could push prices even lower. This week analysts at Morgan Stanley made the case for US$20 oil based on the strengthening value of the U.S. dollar, which tends to push commodity prices lower.

Others have been even more pessimistic for longer, and their forecasts, once mocked, have taken on new gravity. In November 2014, when oil was still well above US$50 a barrel, U.S. financial analyst Gary Shilling, the author of The Age of Deleveraging, predicted oil would fall to between US$10 and $20 a barrel as producers in the U.S. and the OPEC oil cartel faced off over which side would curtail output first. This week Shilling reiterated his call. “Once the wells are drilled and the oil is flowing, the question becomes: what is the cost to get it to market? In the Permian Basin in Texas, that’s $10 to $20, and in the Persian Gulf it’s even lower,” he says. “They’re playing a game of chicken over who can stand lower prices the longest before a producer pulls out.”

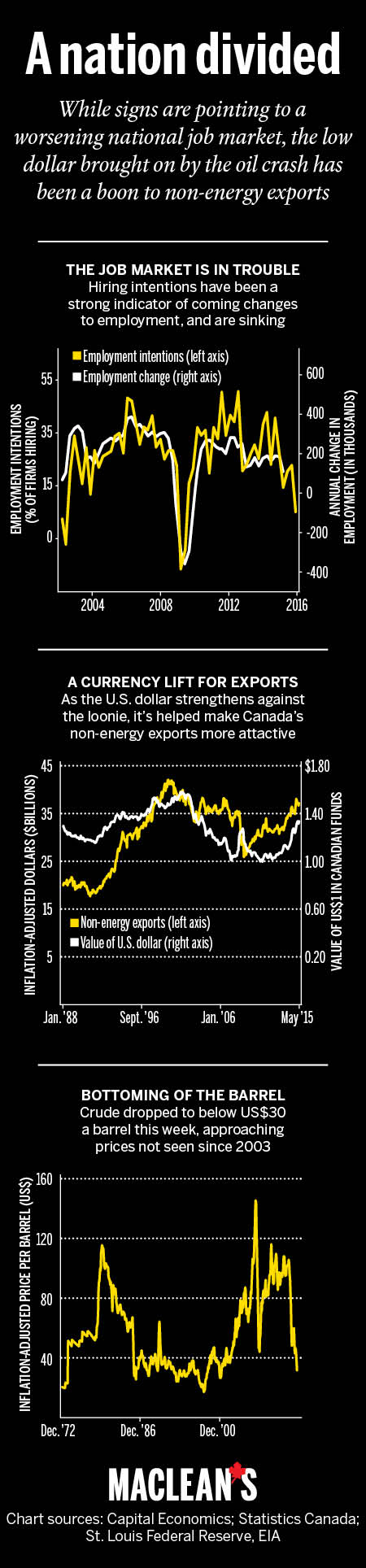

Caught in the middle, of course, is Canada. While the shock was at first expected to be focused mostly on energy-producing provinces like Saskatchewan, Newfoundland and Labrador and the economic driving force of Alberta, there are now very real signs the pain is spreading to other regions. Last week Bank of Canada governor Stephen Poloz reminded the country of the hit we’re collectively taking: the drop in oil has delivered a $50-billion cut to Canada’s national income, equal to $1,500 per year for each man, woman and child. Then this week the Bank released the results of its latest business outlook survey, which polls firms on their investment and hiring intentions.

Related: The A to Z of the oil crash

“The negative effects of the commodity price shock … are increasingly being felt across most regions and sectors,” the report said, with business investment intentions falling to the lowest level since the 2008-09 recession and their hiring plans hitting 2010 lows. “When you look at the levels of these surveys of investment and hiring intentions, they’re historically consistent with negative growth,” says David Madani, the chief economist at Capital Economics, who says it’s a sign that “perhaps the economy is on the verge of a full-blown recession.”

Yet cheap oil offers a huge upside for consumers, and there remain plenty of optimists who believe that low oil and the beaten-down loonie—which dipped below US70 cents for the first time since 2003 this week—will not only provide a buffer against events unfolding in Alberta, but lead Canada’s manufacturing and non-energy export sector to new heights.

So what is unbelievably cheap oil: a blessing? Or a burden?

Back in mid-2014, before the oil crash began, Poloz addressed the imbalance between Canada’s oil-rich regions and the suffering rest. “We see a two-track economy,” he said. Now the direction of those tracks is fundamentally reversed, and Canada’s economic fate comes down to one question: can the old laggards pick up speed fast enough to head off a calamity?

Has it really been 10 years since a freshly minted prime minister Stephen Harper declared Canada an “emerging energy superpower”? It certainly hasn’t been that long since the world was hailing Canada for its resilience during the Great Recession. Envious observers in the U.S. and Europe talked of replicating Canada’s mix of fiscal prudence and regulatory oversight, while everyone wanted a piece of the economic action. Five years ago this week, Target (remember them?) announced its “bold” expansion here, joining a slew of American retailers hoping to capitalize on the relentless Canadian consumer. Foreign investment firms rushed to open shop. And with the loonie above parity after a decade-long commodity boom, the old demons of the 1990s—fiscal and political uncertainty, the brain drain, the hollowing out of Canada—seemed finally behind us.

Related: Was Stephen Harper the enemy of oil?

One by one, those beliefs and assumptions that affirmed our sense of economic exceptionalism have begun to unravel, and have been replaced by anxiety about where our growth will come from.

Nowhere is this more true than Alberta, of course—ground zero of the oil crash in Canada. After a year in which the oil patch shed close to 40,000 jobs, 2016 is expected to bring even more layoffs. That is having a knock-on effect across the province in real estate, auto sales and other business activity. The province has seen its unemployment rate jump from 4.4 per cent in October to seven per cent last month. The government’s finances are a shambles. Even man’s best friend has not been immune: Fort McMurray’s only animal shelter was inundated with surrendered animals before Christmas.

Nowhere is this more true than Alberta, of course—ground zero of the oil crash in Canada. After a year in which the oil patch shed close to 40,000 jobs, 2016 is expected to bring even more layoffs. That is having a knock-on effect across the province in real estate, auto sales and other business activity. The province has seen its unemployment rate jump from 4.4 per cent in October to seven per cent last month. The government’s finances are a shambles. Even man’s best friend has not been immune: Fort McMurray’s only animal shelter was inundated with surrendered animals before Christmas.

Related: The death of the Alberta dream

As bad as Alberta’s woes have been, non-energy regions have taken some slight measure of comfort in the belief—repeated by politicians, economists and bankers—that the pain would be contained to the Prairies.

But there are several ways the Alberta downturn could be transferred to other parts of the country. The most obvious is in the outsized importance of the Prairie province to Canada’s GDP and internal trade numbers during the boom years, and the gap it now leaves. In the first few years after the Great Recession ended, Alberta contributed roughly the same share to real GDP growth as Ontario, a province with a population 3.3 times larger. At the same time, business investment came to focus more heavily on opportunities in the oil patch. Poloz noted the shift last week: “Back in 2002, when oil prices were around US$25 per barrel, investment in the oil and gas sector represented about 17 per cent of total business investment here in Canada. By 2014, that figure had jumped to 30 per cent.”

Businesses in other parts of the country also benefited greatly from their exports to Alberta. According to Doug Porter, chief economist at Bank of Montreal, roughly 20 per cent of Canada’s manufacturing sector is tied to oil and gas.

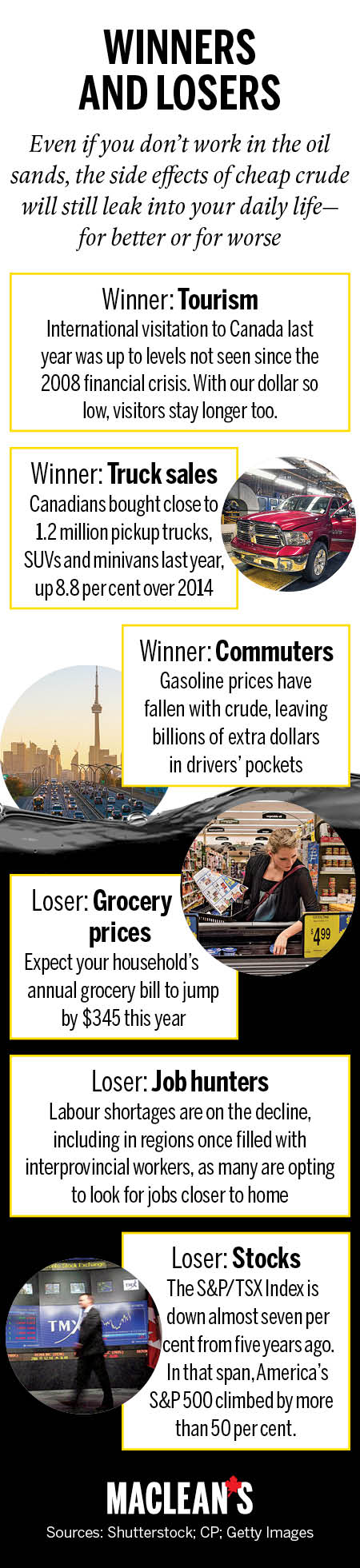

The collapse in oil and other commodities has also weighed heavily on Canada’s stock market, which has fallen 20 per cent since mid-2014. The S&P/TSX Index is actually down nearly seven per cent from where it was five years ago, while during that time the U.S. S&P 500 is up more than 50 per cent. Porter says thanks to this, coupled with the volatility of the loonie, business and consumer confidence have suffered beyond Alberta’s borders.

The shares of Canada’s big banks are certainly feeling the hurt, as investors try to determine their full exposure to the oil patch. Fears that Canadian households are more indebted than they’ve ever been, both inside Alberta and out, amid such a stagnant economy—is also weighing on the banks.

To that end, bank CEOs used a financial services conference this week to assure investors the contagion will be limited, and that they have a firm handle on the credit quality of their loans to the energy sector. Bill Downe, the CEO of Bank of Montreal, said his bank is stress-testing its energy loan portfolio with oil at US$25 a barrel in mind. “You’ve got to ask yourself, how low could it go?” he said.

Still, the worry persists that heavily indebted energy companies may struggle to repay their loans. “When any sector goes on a downturn, the banks tend to pull back on the loans they’re willing to extend,” says Madani. “That makes the downturn all the greater.”

Tighter credit would hamper an already weak job market across the country. While the latest labour report from Statistics Canada for December beat expectations—close to 23,000 new positions were added—those gains were overwhelmingly in part-time or self-employed positions, and they went almost entirely to those aged 55 and older, bypassing the key 25 to 54 demographic. Last year, self-employment accounted for more new jobs than the private and public sectors combined. Of the previous four times that occurred, three came during recessions while the fourth was in 1995 as Ottawa cut government jobs to balance the federal budget. One thing that’s likely holding down employment across the country is the exodus of workers from Alberta, which the Bank of Canada noted in its business outlook survey is under way.

Even as Canada’s job market softens, the collapse in the loonie is putting a pinch on family finances. The majority of fruits and vegetables in Canada are imported, so the lower dollar means grocery stores have to pay more for produce—costs they’re passing onto consumers. The average Canadian household spent $325 more on food in 2015 than the year before, according to research from the University of Guelph Food Institute, and that’s expected to rise another $345 in 2016.

It’s an all-too Canadian story: one key sector falters, and the whole economy swoons. Logic dictates that the effects will even out—some businesses will benefit from a devalued loonie, while regions crippled by soaring oil prices five years ago will recover (hold tight, Ontario). The pain feels acute just now, says Porter, because those benefits take time to work their way through the system. “Canada has been through not just years but decades of very low commodity prices before,” he says, “and that didn’t consign us to decades of low growth.”

It’s an all-too Canadian story: one key sector falters, and the whole economy swoons. Logic dictates that the effects will even out—some businesses will benefit from a devalued loonie, while regions crippled by soaring oil prices five years ago will recover (hold tight, Ontario). The pain feels acute just now, says Porter, because those benefits take time to work their way through the system. “Canada has been through not just years but decades of very low commodity prices before,” he says, “and that didn’t consign us to decades of low growth.”

In fact, green shoots have been rising in places you might be forgiven for thinking were doomed to inexorable decline. Even as the dollar crashed this week, central Canada was riding a year-long surge of international demand for the products that once defined its industrial heartland: consumer goods, electronics, cars and automobile parts. Exports to the United Kingdom and China both rose, by 36.2 per cent and 19.7 per cent respectively, and if you subtract energy products, the country’s export economy had expanded by at least 13 per cent. “It’s healthy growth,” says Mike Holden, an economist with the Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters. “It just took longer to happen than you might have expected. The impacts of a falling currency don’t occur overnight.”

True to Canadian form, the winners haven’t done a lot of crowing—afraid, no doubt, that the good times can’t last. But look hard enough and you can find them. In the car-making capital of Windsor, Ont.—hard-hit in the last decade by the shift of auto production to Asia, Mexico and the U.S.—fully 8,100 people landed manufacturing jobs in 2015, thanks in part to Fiat Chrysler opening a newly retrofitted assembly plant. One local maker of factory machines, CenterLine Ltd., has seen sales double since the loonie went into decline and expects 25 per cent more growth in 2016. Lumber mills across the country, meanwhile, are running near full capacity, as exports of forestry products jumped 9.4 per cent, or almost $300 million. Furniture makers are shipping as much as they can south, with Winnipeg-based Palliser Furniture recently announcing it plans to open up a massive new showroom in Las Vegas for American retailers.

Of course, we’ll need a lot more such added-value jobs to fill the void left by the oil bust. But the sinking loonie and low fuel prices have other upsides. The tourism industry—oft overlooked despite its $88-billion annual contribution to the economy—has a chance to make up ground it began losing in 2001, when the Sept. 11 attacks scared Americans into staying home. Over the following decade, Canada tumbled from the eighth-most-visited country in the world to No. 17, while our annual take from international tourists fell nearly 13 per cent.

Today, there are signs of a turnaround. More Canadians are vacationing in their own country, while Brits, Germans, Chinese and Americans are showing up in larger numbers. Last year, Canada returned to international visitation levels seen before the financial crisis in 2008: arrivals by both air and vehicle went up about seven per cent. That’s an important gain, says Rob Taylor, vice-president of public affairs at the Tourism Industry Association of Canada, because, plainly put, foreign tourists are worth more. “If you’re coming from outside the country,” he says, “you’re likely to stay longer and spend more.” And when it comes to attracting Americans, the low price of gas helps. Border crossings like B.C.’s Peace Arch crossing and Niagara Falls, Ont., saw big bumps last year in incoming traffic.

Today, there are signs of a turnaround. More Canadians are vacationing in their own country, while Brits, Germans, Chinese and Americans are showing up in larger numbers. Last year, Canada returned to international visitation levels seen before the financial crisis in 2008: arrivals by both air and vehicle went up about seven per cent. That’s an important gain, says Rob Taylor, vice-president of public affairs at the Tourism Industry Association of Canada, because, plainly put, foreign tourists are worth more. “If you’re coming from outside the country,” he says, “you’re likely to stay longer and spend more.” And when it comes to attracting Americans, the low price of gas helps. Border crossings like B.C.’s Peace Arch crossing and Niagara Falls, Ont., saw big bumps last year in incoming traffic.

The challenge, says Taylor, is to seize the momentum. After years of ignoring the U.S. tourism market, Ottawa is partnering this year with Canada’s tourism industry on a $67.5-million shared-cost marketing campaign in the U.S. aimed at drawing 400,000 more visitors over the next four years.

The initiative typifies a growing belief that, while a low dollar will indeed revive moribund industries, the country’s long-term future lies in selling services to people in other countries. Last August, the Conference Board of Canada noted that service industries defied last year’s brief recession, and now account for 70 per cent of the country’s GDP. More to the point, Canada’s export economy was driven during that period by services provided abroad, from management consultation to technological advice. Financial services and insurance led the way, doubling in foreign sales between 2003 and 2013. One of the few sure outcomes of the current turmoil is that a low dollar will accelerate this growth.

Another certainty: that we’ll all get some kind of break from crippling fuel prices. Seventeen months ago, with gas brushing $1.40 per litre, Canadians stood appalled at pumps watching price meters whiz higher—an average fill-up cost $90. “I’d wonder how much I could possibly do this,” Julie Vitro, who commutes 60 km each way from her home in suburban Woodbridge, Ont., to her teaching job in southwest Toronto. Vitro’s Mazda 3 is no gas guzzler. But keeping it fuelled up was costing about $360 a month, she says, while weekend ski trips in the family’s Hyundai SUV began to feel like an unsustainable luxury. “If it had continued to go up, I’d have had to move jobs, to a school closer to our home,” she says.

These days, Vitro’s fuel bill is down by a full third, allowing her and her husband, Mitchell, to carry on with the routines they’d worked hard to establish. She’s not the only suburbanite feeling like her way of life has been granted new licence by the oil crash. Property prices have held steady, despite predictions that long commutes and pricey fuel would result in empty stretches of track housing along the edges of Canadian cities. A recent jump in sales of SUVs and light trucks, meanwhile, speaks to renewed confidence in the auto-centred lifestyle that, until recently, urban critics suggested could not continue.

Truth is, says Tsur Somerville, an urban economics professor at the University of British Columbia, North Americans do not typically make decisions on where to live based on fluctuations in oil. “I never thought everyone was going to move downtown,” he says. “Not everybody wants to live in a condo.” If anything, Somerville notes, new suburbs have started incorporating features of urban culture that suburbanites now want, such as pedestrian-friendly neighbourhoods and commercial strips. To them, a short-run drop in fuel prices will feel like a pat on the back.

As the different factions of Canada’s economy struggle to adjust to the oil crash, the mystery remains: where will prices be next year, let alone five or 10 years from now? A sharp rebound in oil would bring with it a higher loonie, delivering yet another one-two punch to the nascent recovery in manufacturing and non-energy exports. On the other hand, if oil lingers at US$30 to $40 for 15 years as it did during the 1980s and 1990s (adjusted for inflation), it would mean new oil sands projects that have recently been postponed would likely be abandoned, while some higher-cost operations that are already up and running might no longer be feasible. And you can kiss any pipeline dreams goodbye.

Related: What we learned from Keystone XL

It’s entirely possible the worst-case oil scenario of US$20 a barrel does not come true. It was only in 2008 that everyone feared oil was headed to unmanageable heights. A Maclean’s cover story that June, drawing on forecasts from economists and oil watchers, examined what life would be like at US$200 a barrel. Oil peaked three months later. Likewise, the last time oil was at US$20 a barrel (after inflation) was March 1999, the same month a cover story in The Economist magazine warned of a world “Drowning in oil.” That marked the low point for prices. “This happens when you go through a major swing because people tend to be overly optimistic on the boom and overly pessimistic on the bust,” says Madani. “For Canada, the problem is oil has already fallen so far, it almost doesn’t matter if it’s at $40 or $20 because the long-run break-even cost for a lot of new oil sands projects is at $60 to $80.”

Even if prices do recover somewhat, there are factors working against oil returning to those levels any time soon. Saudi Arabia appears committed to pumping out crude as a way to recover market share lost to non-OPEC countries like Canada, the U.S. and Russia. At the same time, the fracking industry grows more efficient by the year. According to Shilling, productivity jumped by 30 per cent in 2014 and 25 per cent last year—and there is a continued growth in alternative energy, shifts to natural gas and the move to electric cars, all of which can’t be ignored when it comes to curbing demand for oil.

Meanwhile, the global energy puzzle is missing one large piece that existed when oil was last at these low levels: an emerging China that had an insatiable appetite for crude and other commodities and a willingness to acquire them at any price. Now China’s era of miracle growth is behind it, the country is teetering under a mountain of debt and there are outright fears of a downturn.

Canada’s dreams of being an energy superpower have been foiled, for now. But there’s nevertheless reason to be hopeful a rebalanced economy will power ahead.