The B.C.-Alberta pipeline fight could undo our national climate plan

Opinion: The climate plan depends on Alberta’s buy-in. Blocking the Trans Mountain pipeline could put that at risk and make it impossible to meet Canada’s emissions target.

Share

Andrew Leach is a professor of energy and environmental economics at the University of Alberta. In 2015 he served as chair of the Government of Alberta’s Climate Change Leadership Panel.

When you think about pipelines and climate change, you probably think about protesters trying to stop one in the name of the other. Since 2011, our news media has been full of images, from both north and south of the border, of exactly that. Keystone XL, Northern Gateway, Energy East and the TransMountain Expansion, as well as the Dakota Access pipeline in the US, faced significant protests which each framed stopping pipelines as a means to fight climate change. This week, the Prime Minister turned the tables. In an interview with the National Observer’s Sandy Garossino, Trudeau spelled out the new tradeoff: “by blocking the Kinder Morgan pipeline, (B.C. Premier John Horgan) is putting at risk the entire national climate change plan.”

Is the Prime Minister Trudeau correct? I think he is. The national climate plan we have today is, in large part, influenced by Alberta’s policies (disclosure: I chaired Alberta’s Climate Leadership Panel). Measures like the federal large final emitters treatment, the coal phase out, and the national carbon pricing backstop policy each approximate policies enacted by the Notley government in Alberta. This is a symbiotic relationship: federal climate policy backstops put a stronger foundation under the Alberta plan and, with the Alberta plan in place, there is a credible although still very challenging path for Canada to meet its 2030 target. Without Alberta’s plan, that credible path disappears. The Prime Minister was correct when he said that, with market access including the proposed Kinder Morgan pipeline, “Alberta would be able to be ambitious as we needed Alberta to be and get on with the national climate change plan.” To meet Canada’s targets, Canada needs Alberta on side.

WATCH: Trudeau focussed on ‘national interest’ in Alberta-B.C. trade war

The Prime Minister also identified the shakiest ground on which his national plan sits—that of unequal treatment between provinces. As he stated, if we get, “politicians who are picking and choosing parts of the national plan they don’t like, and if we don’t continue to stand strongly in the national interest, the things that people don’t like within the agreement—which is always filled with compromises—are going to mean that there is no agreement, and there is no capacity to reach our climate targets.” The federal plan, through it’s two-lane approach, has already opened the door to higher carbon prices in some provinces than others, and the burden of coal phase-out regulations announced last week as well as methane regulations being revised as we speak will each fall most heavily on a couple of provinces. A pipeline could easily be (I’m sorry to have to do this) the straw that broke the climate plan’s back.

If B.C.’s efforts to block the pipeline result in the loss of Alberta’s faith in the federal process and the government’s ability to defend parts of its policies against assault from individual provinces, the alternative is clear. If the Prime Minister finds himself facing strong opposition from Alberta and Saskatchewan strongly opposed, a fight over a hybrid solution proposed by Manitoba, and a fight with the maritime provinces over coal power, he is in trouble. Combined with whatever the Ontario election might bring, it’s not-at-all clear the national climate plan survives. That would, without a doubt, lead to far greater consequences for our national emissions inventory than any single pipeline could portend.

MORE: Pipelines aren’t just an Alberta issue—they are crucial to national prosperity

Let’s take that trade-off at face value and compare the potential stakes at play if the TransMountain Expansion were to go ahead versus an outcome where it does not, but at the expense of the national climate change plan.

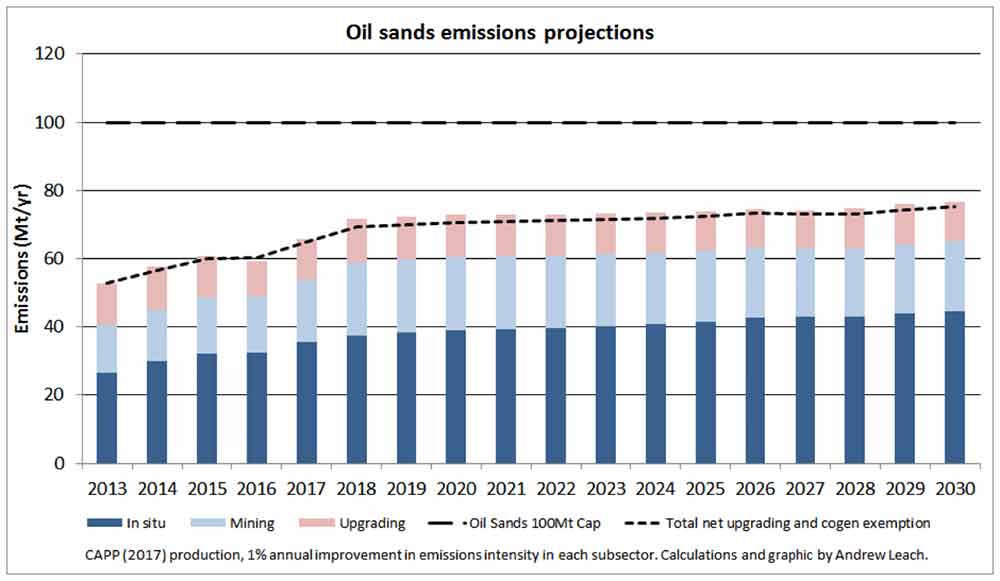

Without pipeline constraints, oil sands emissions are expected to grow significantly, although not by as much as would have been forecast a few years ago due largely to the impacts of lower oil prices. The graph below shows my current approximation, with assumptions detailed in the graph caption—annual emissions rise to 77 megatonnes (Mt) by 2030.

This forecast implicitly assumes new pipelines. Without incremental pipeline capacity, there would be significant reductions in the value received for oil sands production and this would likely further limit the amount of growth and production-sustaining capital investment we would see. In 2016, the National Energy Board estimated what a no pipelines scenario with these type of price impacts would mean for oil sands production. After modifying those projections to reflect reduced overall production numbers and converting them to a GHG emissions forecast, we’d expect blocking not just TMX but all new pipelines to result in approximately 8 Mt fewer emissions per year by 2030.

Reducing emissions by 8 Mt/yr is certainly material, but it’s not remotely comparable to the impacts of other policies in Alberta, let alone the national climate plan. For context, each of the Genesee, Keephills and Sundance coal power plants in Alberta had emissions above 8 Mt in 2016. Policies like the phase-out of coal power alone will have multiple times the impact of blocking a single pipeline.

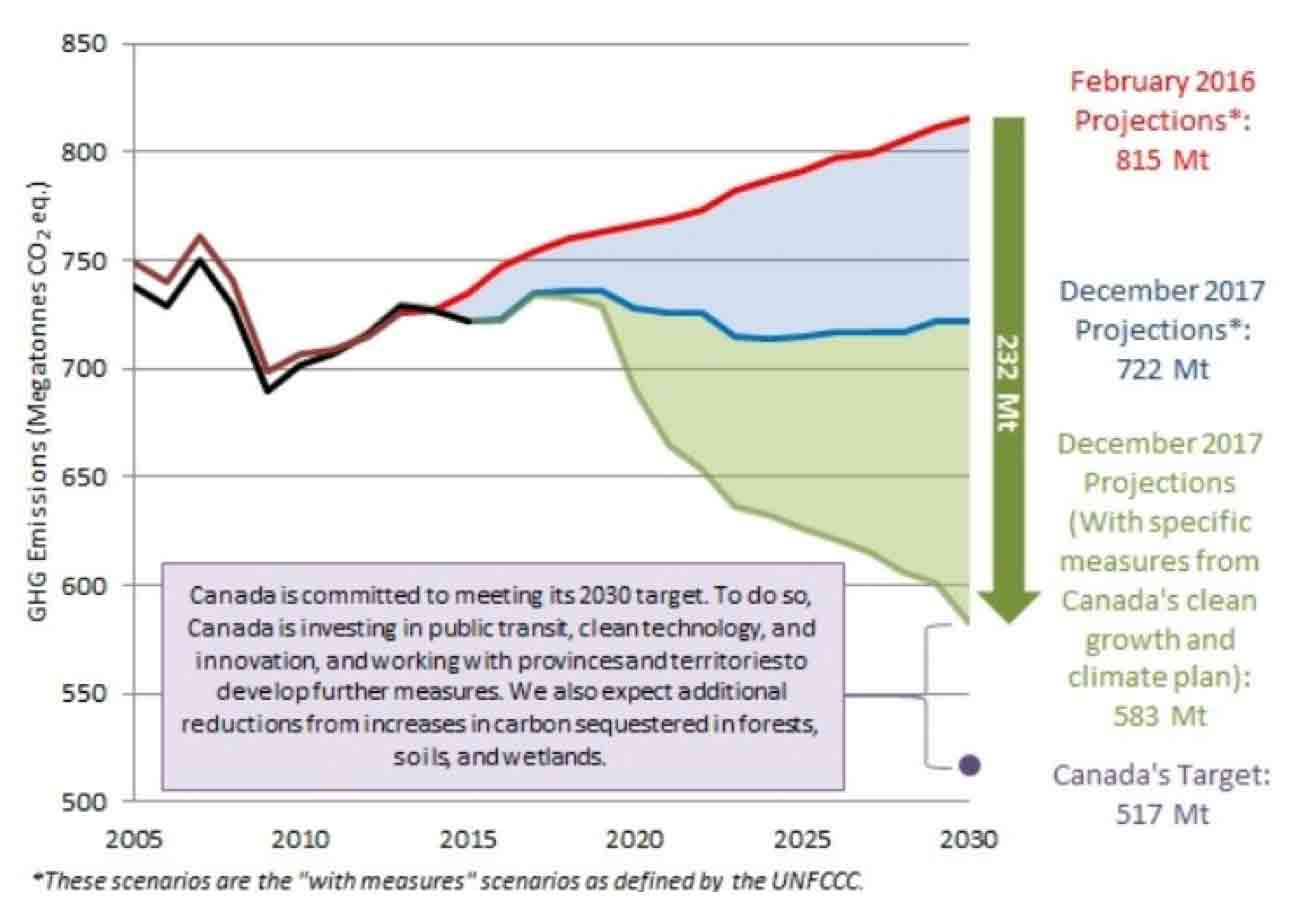

By contrast the Pan-Canadian framework, announced in December 2016, is expected to yield significantly more emissions reductions. The most recent national reporting to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change projected that measures implemented and under development would lead to a 232 Mt decline from what was projected in early 2016. Yes, economic conditions have also impacted these projections, but policies including the coal phase out, the national carbon price, and methane regulations play a major role.

What would emissions be in the absence of the Pan-Canadian framework but with no new pipelines? It’s hard to say, and certainly more work than this post will allow, but they are, without question, much higher than the projections we are seeing today from Environment Canada. It’s easy to see an impact at least 10 times as large as the potential gains from blocking the TransMountain pipeline.

As the Prime Minister said in his interview with Garossino, there is going to be dissent across the country: “There are parts of that national climate change plan that prairie conservatives don’t like, they don’t like the national price on carbon. There are parts that certain people in B.C. don’t like, the Kinder Morgan pipeline for example. There may be other parts that other people have issues with.” Some will want more stringent policy. Some will want less. Some will want more emphasis on large emitters or more money for new technology. The list will be endless.

However, there is one element on which a national climate change plan will always depend—a functioning federation. Over the next year, it’s going to face some tough tests. If the federation fails Alberta on federally regulated pipelines, it should not expect Alberta to continue as a leading partner in our efforts on climate change.

MORE ABOUT PIPELINES:

- Trudeau and resource projects: the urge to get it done

- How Trudeau hasn’t left himself any wiggle room on pipeline politics

- How B.C. and Alberta can get out of their trade war before it gets worse

- Alberta’s strong carbon policy is key to getting pipelines built

- A B.C. pipeline spill would be inevitable. But who would pay?

- Justin Trudeau’s mid-life crisis

- Why oil sands protesters and companies both get it wrong