The closer you look, the weaker Canada’s job market appears

A refined look at the data shows that some demographics in the labour force are enduring near-historic unemployment rates

Share

This story first appeared in Canadian Business.

Depending on who you listen to, Canada’s labour market is either incredibly strong or it is in freefall. Both sides of the discussion are armed with data to support their argument. Who should we believe and which datasets provide the most accurate picture of the state of the labour market?

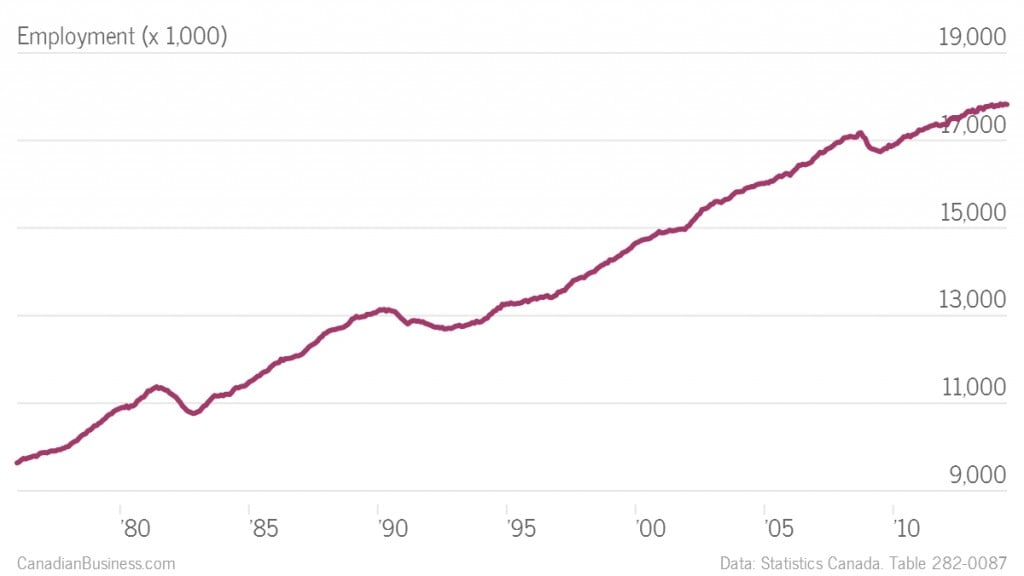

A few days ago I was listening to a caller on an AM radio show promote the government’s economic record by stating that there are more Canadians with a job today than at any point in Canada’s history. This claim is backed up by evidence.

The claim that the number of Canadians with a job is at an all-time high is factually true, but misleading due to population growth. There are over 17 million Canadians with a job today; Canada’s population in 1956 was only 16 million. Since looking solely at the absolute number of people with a job is far from ideal, other metrics should be considered.

Unemployment Rate

The most commonly used metric on the health of the labour market is the unemployment rate. Canada’s unemployment rate is currently hovering just over 7 per cent.

The unemployment rate is far from a perfect labour market barometer due to the discouraged workers problem. As Miles Corak explains, the unemployment rate does not simply measure the percentage of the population without a job:

To be considered “Unemployed” a survey respondent must not have done any work for pay during a particular week of the survey month, must be available for work, and—most crucially—must have done something to find a job during the last four weeks.

A laid-off manufacturing worker who has given up hope of ever finding another job is not counted in the unemployment statistics, so an economy with a high number of discouraged workers could have a misleadingly low unemployment rate. Conversely, an economy where people are optimistic they can find work could have a deceptively high rate of unemployment. The unemployment rate is a useful statistic but far from a perfect one, so I believe the caller was right to focus on employment rather than unemployment metrics.

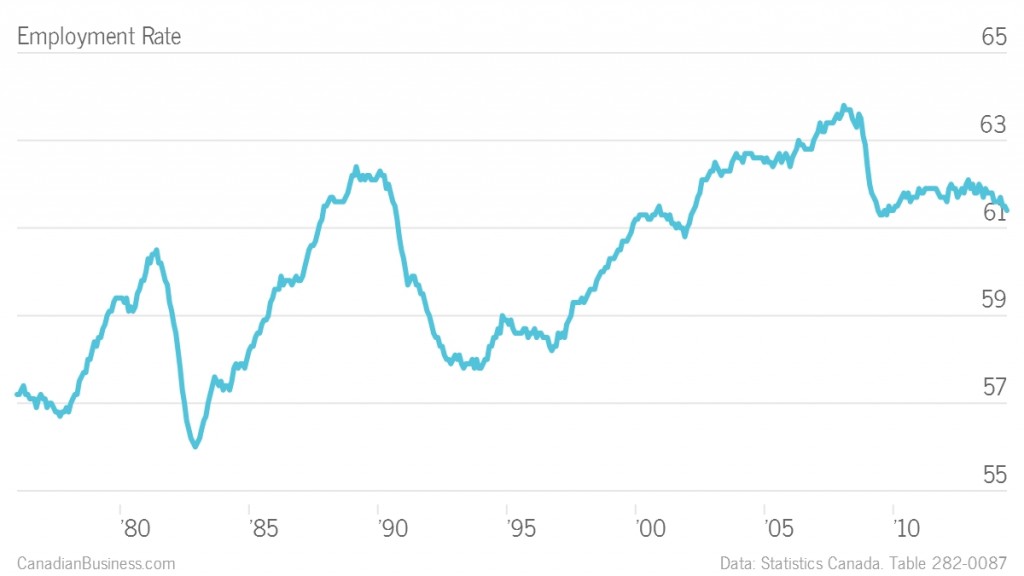

Employment Rate

To account for population growth, we can use the employment rate, which measures the percentage of the working age population that has a job. Canada’s employment rate fell during the recession and has recovered little since.

Like the unemployment rate, the employment rate is a useful but imperfect measure. Canada defines the “working age” population as anyone “15 years of age and over.” As such, it includes everyone from Grade 10 students to 95-year-olds. A country with a lot of young people or a high proportion of seniors will tend to have a lower employment rate, so this metric is affected by both economic conditions and demographic shifts such as the baby boomers entering retirement age. We can control for this by limiting the discussion to “prime aged” workers.

Employment Rate for 25-54 Year Olds

To control for demographic effects, we take out groups that are often still in school (24 years and younger) or can potentially enter early retirement (55 and up). There are other endpoints we can use, but limiting the discussion to 25-54 year olds is the most common approach. Under this measure, the employment rate is at a near all-time high.

This measure would seem to imply that the labour market has consistently improved over the last 40 years, which seems unlikely. What is largely being captured in the 25-54 year old employment rate data is the increased number of women in the workforce.

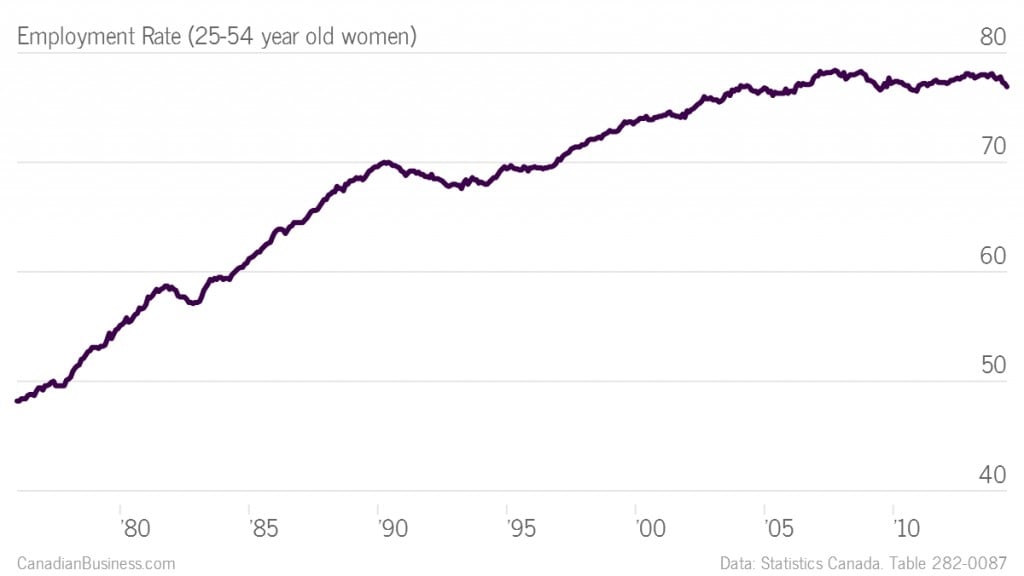

Employment Rate for 25-54 Year Old Women

One of the most important social trends since World War II is the percentage of working age women in the workforce, which has doubled in the last 50 years.

The easiest way to separate out changes in the employment rate due to the strength of the economy from changes in the employment rate due to social changes is to examine the employment rate for men between the ages of 25-54.

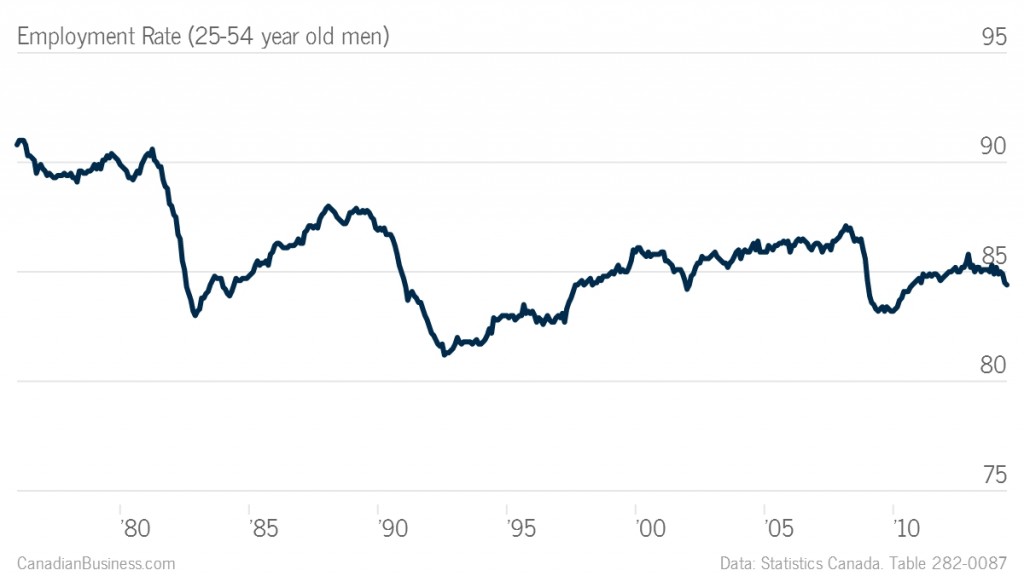

Employment Rate for 25-54 Year Old Men

The employment rate for 25-54 year old men fell during the recession, recovered somewhat, but has been flat over the past few years. It is currently at 84.4 per cent, a level well below Canada’s 1999-2008 average:

There are still a number of other factors we have not accounted for, including job quality. We should account for the possibility of underemployment, where people who could work a full-time job are only working part-time due to the weakness of the labour market.

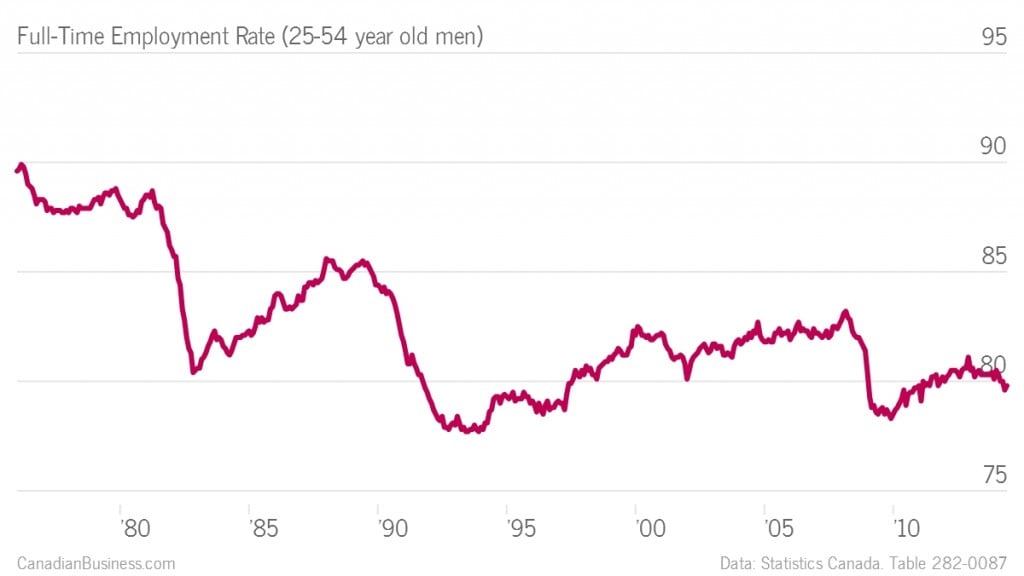

Full-Time Employment Rate for 25-54 Year Old Men

If we restrict the analysis to 25-54 year old men that have a full-time job, the picture changes somewhat. Outside of the 1992-97 period, the employment rate for this group has been at lows not seen in the nearly 40 years of data that is available:

If I were limited to a single metric to use for the health of the labour market, I would use this one. But limiting ourselves to one measure is ill-advised. There are a number of factors we could still control for, such as the ratio of new Canadians to those born here. We have said nothing about wages and the labour market struggles of new graduates and women are important and not captured here. But to properly analyze the health of the labour market, we need to control for demographic, population size, nature of work and social changes. Simply citing the unemployment rate or the number of people with a job is not enough. But by controlling for these factors, we see that the Canadian labour market is not particularly strong.