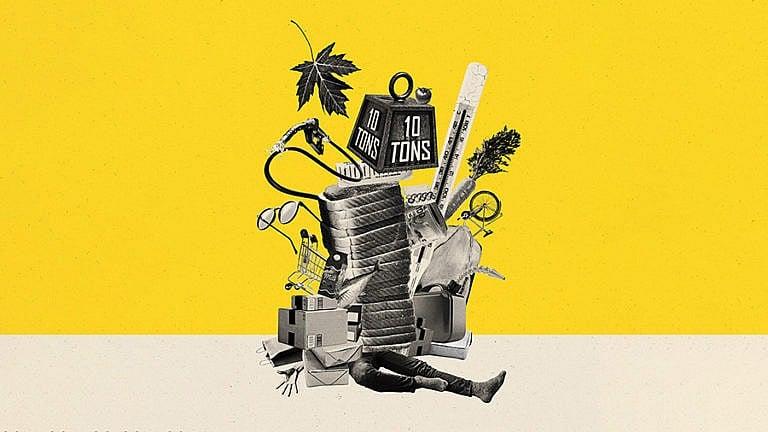

Inflation is about to get way worse in 2022

Canada is headed for an economic inflation that won’t rival the double digits of the 1970s, but the experts say you’ll definitely feel it

(Illustration by Klawe Rzeczy)

Share

To follow Blake Doyle’s life and work in Charlottetown is to take a madcap tour of inflationary Canada. In this regard, he’s like everyone on Prince Edward Island, where Statistics Canada shows the cost of living has risen further than in any other province. Gasoline pushed close to $1.50 per litre in late October. At the supermarket, chicken breasts cost about $3 per kilogram more than a year earlier, while the price of a block of butter had fattened by $1.63, to $5.29. Although real estate isn’t the nightmare it is elsewhere in Canada, housing costs have risen by 10.7 per cent in a year, more than double the national average.

But few perspectives capture the breadth of this worrying picture quite like that of Doyle, a proud local businessman with a varied portfolio of companies, services and properties. At his residential rental buildings, energy costs are rising by more than the government allows landlords to hike rents. His human resources and recruitment firm frequently hears about employers’ struggles to find and keep staff; most haven’t yet raised wages, he says, but will probably have to. His brother runs an outdoor goods retailer where everything is in demand and supplies keep running low, especially bikes and bike parts. At Doyle’s eyewear shop, supply shortages have forced him to limit his selection of frames, though for now he’s reluctant to make customers pay more. “We’re still happy to try to get clients,” he says, “so we don’t want to impact our prices too much.”

MORE: Five strange things that were up for rent in the ‘sharing economy’

Across Canada, household costs in 2021 went on an upward ride unlike anything seen in nearly a generation. The countrywide inflation rate in September hit 4.4 per cent, the highest since 2003 (in P.E.I., it reached a blistering 6.3 per cent). And the turbulent climb seems nowhere near done. The Bank of Canada forecasted inflation worsening in late 2021 to around 4.8 per cent—a three-decade high—and continuing above target levels well into the new year.

The result will be an economic chain reaction affecting nearly everyone in the country. Families will spend more to stock their refrigerators and heat their homes; faced with rising costs, workers will demand higher wages from employers who are shelling out more for rent, supplies and merchandise. But if the central bank moves to tame these effects by hiking interest rates, mortgage costs will rise—sharply, for many—and businesses will pay more to borrow money, blunting any relief from the lower relative prices. “It’s not the double-digit inflation of the ’70s,” says Sohaib Shahid, director of economic innovation at the Conference Board of Canada. “But I think the pinch will be felt.”

You could forgive some older Canadians dismissing all this as the hand-wringing of the avocado toast set. It pales next to the long stretches of hyperinflation in the late 1970s. But it is a jolt after an extended period of tranquility and lazily rising prices. Before the Consumer Price Index spiked to 3.4 per cent in April, year-over-year inflation hadn’t been above three per cent in any monthly reporting period since late 2011. And it stayed above that level, a caution marker for the Bank of Canada, through to the end of October, the longest stretch since the early 1990s.

There was disagreement in the fall between Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem and private bank leaders about whether this is a transitory cycle or something more structural and prolonged. Macklem initially chalked it up to surging oil prices and temporary disruptions to the global supply chain. As reassurance, he’s cited the recent shock to lumber prices that ultimately receded once supply rose again to align with demand.

Other experts believe the supply chain will take longer to come unstuck, and that Canadians who’ve saved during the pandemic will spend quickly, flooding the economy with consumer dollars when demand is already unbalanced. Over the course of October, Macklem gravitated toward their view, saying pressures would remain more “persistent,” while the central bank adjusted its inflation forecast accordingly.

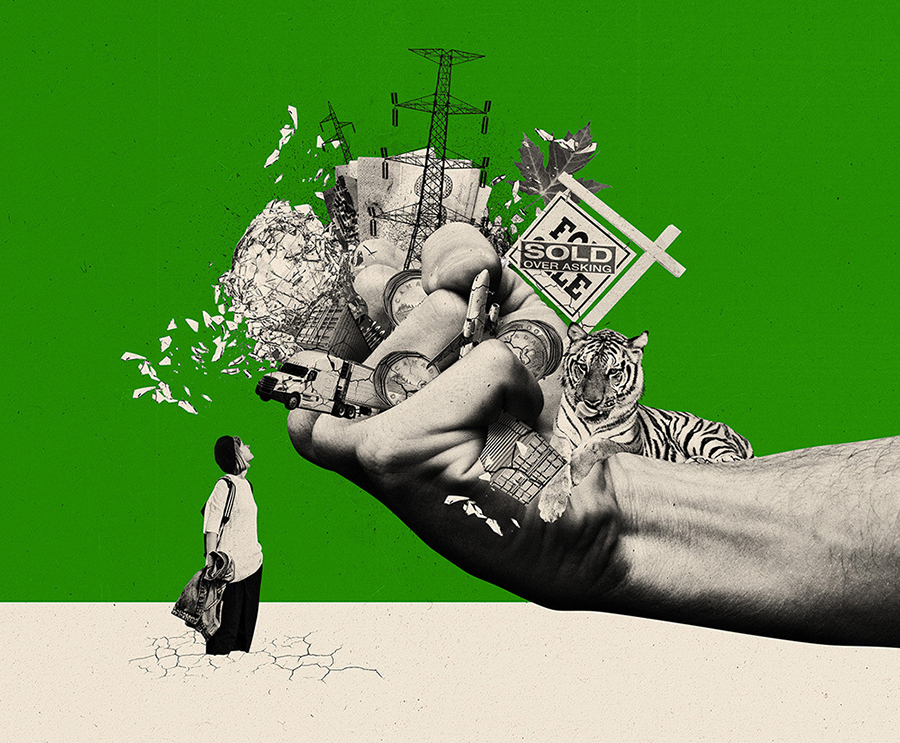

There’s no debate, however, about who gets hurt in such times: Canadians who already struggle to make ends meet. The 20 per cent of families with the lowest incomes spend about one-third of total earnings on shelter, while the top 20 per cent spend one-fifth, notes Shahid. Those in the lowest rung spend 15 per cent of their incomes on food, compared to the highest rung’s eight per cent. And the less wealthy bear the brunt of rising energy costs, as they tend to live in less energy-efficient homes. So more low-income families will face a dilemma, Shahid says: pay down energy bills or spend on other necessities of life.

That’s the nub of the problem. It’s not nice-to-have items like new furniture, yoga pants and restaurant meals that account for the bulk of inflation, wrote Scotiabank’s Derek Holt in a recent note, it’s the must-haves. “When it’s your home, your car and fuelling it, your grocery bill and your utilities that are driving the biggest weighted contributions to inflation, then clearly we’re looking at something impacting a rather large chunk of a typical household’s budget.”

This reality has been arriving at the doors of food banks nationwide. The one in Prince Albert, Sask., saw 25 per cent more clients in 2021 than the year before, even as government pandemic benefits buoyed struggling residents. When Thanksgiving came around, the food bank didn’t have turkeys to hand out, as it usually does, because nobody donated the suddenly pricier poultry. At a low-cost vegetable growing operation called Jenny’s Garden, located on the outskirts of the northern Saskatchewan city, Bonny Sanderson says she served more families, and they’re stocking up like they hadn’t before. One family recently drove a full hour to the not-for-profit family farm to fill their trunk. “They can only afford so much, so they came to us to get enough potatoes, cabbage and carrots to last them for the winter,” Sanderson says.

The last thing most business owners want to do is raise their prices, says Simon Gaudreault, vice-president of national research at the Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB). But when firms face higher energy and transportation costs, or are forced to import products by plane because ships won’t arrive nearly fast enough, there’s not much wiggle room. According to an October survey, members of the small business association planned to hike prices by an average of 3.9 per cent, a figure far above any level since the CFIB launched the monthly questionnaire in 2009. Unknowns around whether the economic recovery will continue, supply chains will clear and COVID is receding for good add to the upward pressure, he says.

Often, soaring consumer prices come in tandem with, and are partly fuelled by, rising wages. That’s been slow to happen this time, even amid the gathering storm of a labour shortage. Workers in Canada’s accommodation and food sectors—many of them less-advantaged Canadians—have received only a 50-cent-per-hour raise on average since before the pandemic, according to Shahid. “Whichever way you slice it, low-income Canadians are bearing the brunt of this crisis,” he says. The CFIB survey suggests most businesses do plan to hike wages—not at a pace that matches overall inflation, but at one that might trigger additional price hikes.

READ: No water in winter. No septic field. For $489,000 the ‘Tom Selleck house’ can be yours.

Suffice it to say, an economic force that hits working-class families hardest risks stirring resentment about inequality. With necessities gobbling up their household budgets and real estate prices still sky-high, renters have less money to put toward down payments. “So what happens when two or three million millennial couples like that wake up one morning and say, ‘You know what? We’re never going to be able to afford a house,’ ” says Conservative MP Pierre Poilievre, who’s been beating the drum about inflation as a major political problem.

The Trudeau government’s efforts on affordability have largely centred on housing initiatives; as inflation became an issue on the campaign trail, the Prime Minister said: “You’ll forgive me if I don’t think about monetary policy.” Enter the monetary policy-makers at the Bank of Canada, who have a mandate to keep inflation around two per cent. In the fall, the central bank stopped its “quantitative easing” practice of pouring hundreds of billions into the financial system, a pandemic-period economic support measure that contributed to inflation. Banks and bond markets expect multiple interest rate increases in 2022 to further temper inflation, and Macklem has signalled the hikes could begin as soon as April.

But this will make borrowing more expensive for businesses and residential mortgage-holders alike. So, while early and aggressive interest rate hikes could snap an inflation streak, they also risk stalling economic growth—just as countries try to recover from the impact of COVID-19. What’s more, governments are much more deeply indebted than they were before the pandemic, raising the risk of a fiscal crunch should rates climb too high too quickly. “The government has decided that the country will live off cheap debt,” says Poilievre. “But the problem with riding the tiger of cheap debt is eventually you get off the tiger, and you end up in its belly.”

MORE: How blockchain could revolutionize food supply chains and lower your grocery bill

Whether such dire scenarios lie in wait for Canadians is no certainty, of course. Global economic trends have a way of mocking predictions. But on inflation, we’re down to choosing between illness and cure, and nothing in the past points to a pleasing outcome. We either pay more in the future to borrow money and service our public debt, or we pay more to do just about anything else. Something’s going to give in 2022, and perhaps for years to come.

This article appears in print in the January 2022 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Look up. Way up.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.