The Fort McMurray wildfire has hit the oil sands hard

Oil sands producers are slashing production due to the fire, and Canada’s economy is feeling the pain

Share

The wildfires raging in Fort McMurray and the surrounding region could shave half a percentage point off May’s GDP and contribute to overall lower growth in the second quarter, according to bank economists, thanks mostly to a 40 per cent drop in production at nearby oil sands facilities. And it’s far from clear when things will get back to normal.

(Story continues below)

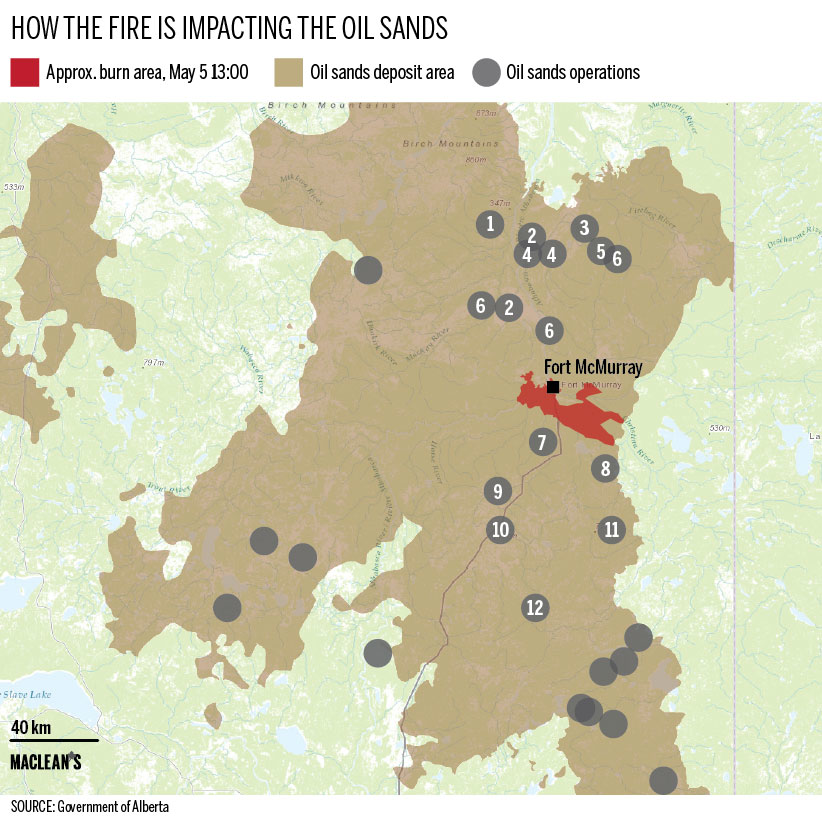

This map and table show the oil sands region and how various operators have been affected by the fire and evacuation. The table was updated on Sunday, May 8.

[rdm-footable id=’707′]

(Source: RBC Dominion Securities, company releases, news reports)

Several major producers, including Shell Canada, Suncor, Nexen and the Syncrude joint venture, have announced precautionary shutdowns or reductions in recent days. (See graphic below.) Some said the decision was due to the need to focus on staff and other evacuees from Fort McMurray, who took up shelter in work camps well north of the city. Others saw their operations impacted by pipeline shutdowns that squeezed off supplies of flammable diluent, which are needed to thin the gooey oil sands bitumen. Still others found themselves in the path of advancing fires. Athabasca Oil Corp., for one, cited “the fire’s proximity and elevated safety risk” for its decision to shut down the company’s Hangingstone project and evacuate workers.

The combined impact of the work stoppages and slowdowns are predicted to reduce the oil sands’ output by as much as one million barrels of day, or about 40 per cent of total production, according to estimates by RBC Dominion Securities. Assuming operations are impacted for a period of two weeks, that could translate into a half percentage point reduction in May GDP growth and contribute to second-quarter GDP growth of 0.5 per cent, down from a previous estimate of 1.5 per cent, the RBC economists said. However, they noted, “the situation remains fluid and uncertainty remains about how long production disruptions will persist.”

The lowered GDP forecast takes into account the impact of the roughly 80,000 people who had to evacuate Fort McMurray, where wildfires have so far destroyed 1,600 buildings. Another estimate, by BMO Capital Markets, suggested the disaster could cost insurers as much as $9 billion if the entire town is razed, or between $2.6 billion to $4.7 billion if a quarter to half the town is impacted. Either way, that would make it the most expensive natural disaster for insurers in Canadian history.

The wildfires couldn’t have come at a worse time for Fort McMurray and the oil sands industry on which it depends. A global oversupply of oil coupled with weak economic growth outside the United States caused oil prices to plummet last year, with the price of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate, the North American crude benchmark, trading as low as US$26 earlier this year. By contrast, many oil sands operations—particularly large-scale surface mines—require average oil prices of around US$80 a barrel to make money. The price of oil is now trading around US$45 a barrel, up about US$1 over the past week—mostly because of the impact of the wildfires.

Even if the fires can be brought under control with the help of Mother Nature, it’s not known how long it will take oil sands producers to get back up and running again. Greg Pardy, an analyst at RBC, said in a note earlier this week that oil producers may have no choice but to fly homeless employees in and out of their work sites until Fort McMurray is rebuilt.