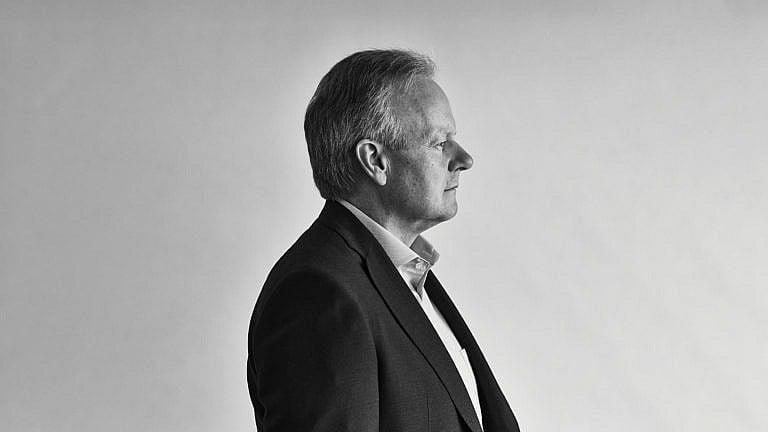

Stephen Poloz on economic dangers ahead, staying positive and lessons from Star Trek

The former Bank of Canada governor talks with Marie-Danielle Smith about his new book, the politics of inflation, and how a near-death experience changed his outlook on life

Stephen Poloz. (Photograph by Jessica Deeks)

Share

Like so many conversations in this era, my talk with former Bank of Canada governor Stephen Poloz happened on a Zoom call. Mostly, we discussed his upcoming book, The Next Age of Uncertainty, a primer on the economic volatility ahead. But we also talked about lessons from the pandemic, the political discourse on inflation, the reasons for his optimism and how two TV characters informed his leadership style. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Tell me about how your pandemic has been going.

A: It coincided with when I stepped down from work. You visualize yourself doing all kinds of travelling, going to places you always wanted to spend two weeks at instead of a few days. None of that has happened. I worked a lot, and it’s amazing how productive you can be just by hardly moving from your chair.

Q: You earned the nickname “Sunny Steve” as bank governor. That’s him talking, isn’t it?

A: Yes, that’s looking on the bright side. Of course it’s been dreadful for many people and it’s been hard family-wise. I had two grandchildren come along during that period of time. I’ve seen them only a little. It makes me wonder what we have to get used to, long term.

READ: Kathleen Wynne on her political downfall and the private advice she gave Doug Ford

Q: You’ve written about what uncertainty is going to look like in the future. What was the genesis of this idea?

A: As governor, it was very apparent that people had a very short-term horizon when thinking about what’s going to happen in the economy. I was invited to speak at Spruce Meadows by Nancy Southern [the CEO of Atco]. It was a real corporate crowd, and they’re exactly the culprits I’m talking about—they think one quarter ahead. That’s where I first broached the idea that longer-term trends could interact and cause unpredictable outcomes.

Q: You don’t see a lot of macroeconomics books targeting a household audience, a government audience and a business audience all at once. You’re trying to do a lot with it.

A: I started to think about how I could help people. Especially decision-makers, whether they’re households deciding their mortgage or companies deciding their plan. What are the big issues they’re thinking about that could affect those decisions over a five- or 10-year horizon? Which we hardly ever think about, but it matters.

Q: You point to a number of “tectonic forces”—population aging, technological progress, growing inequality and climate change—and argue they will cause greater uncertainty and volatility overall.

A: With businesses, there’s such a complex planning environment. [They] will claim to their board that they’re looking at the long term, and if the world turns out really badly, this is what it’s going to look like. Or if the world turns out really good. But I think they spend less time than they should exploring what they will do when those good or bad things happen, because they’re more likely now.

Q: You explain this as if a bell curve is becoming more of a straight line.

A: What you think of as your main scenario has lower probability associated with it, and there are many more possibilities spread out there. So you need to be more prepared for those possibilities.

Q: The pandemic was a rare scenario. What did we learn from how the economy handled it?

A: This episode taught us some new things. First of all, the starting point matters a great deal. Canada was in the best shape it’d been in for 40 years. Inflation was exactly on target for the first time in a long time. Unemployment was at a 40-year low. It’s like when the Ferrari of athletes gets a cold. It lasts two days because they’re in such great condition. You can see the differences around the world. Economies that weren’t in that situation suffered more. The second important lesson was fiscal policy [like CERB] can do a really good job of stabilizing the economy. A third one is collaborating with the banks. They played a really important stabilizing role.

Q: What are your thoughts on the inflation debate that is happening in Canadian politics right now?

A: It runs the gamut from plain wrong to just unthoughtful. What I like to do is measure inflation based on February 2020, before the pandemic. You’ll find that, sure enough, overall the price level is up by 4.9 per cent over 21 months. Well, that’s quite a lot. But if you translate that into what would be the equivalent 12-month average rate, it’s about 2.8 per cent. And we know underneath that it’s all about oil. If you take food and energy out, which economists often do, it’s 2.1 per cent.

Could it still be picking up? Yes, I’d say that’s a risk. But people aren’t doing a very careful job of understanding what prices have done. Supply chain issues will also get worked out—there’s too much money at stake for companies to not figure those things out. And the big counterargument, which I want to remind people of, is that the fourth industrial revolution [driven by artificial intelligence and biotech] will cause a lot of prices to fall.

Q: But it’s politically advantageous, especially with food and gas prices on the rise, for politicians to lean on messaging about what or who is causing inflation.

A: Politics is rarely clarifying. But I do think that with something as important to people as the prices they face every day, all parliamentarians have a job to do, which is help people understand what they’re seeing, rather than just pointing fingers.

Q: In the book you also criticize the political debate around globalization for ignoring the benefits of trade liberalization.

I’ve been in the policy-maker game for, like, 40 years. And I feel like, almost every week, I need to explain yet again what you’re talking about. If I say trade deglobalization is going to raise the prices of all these things you buy from Costco or Walmart or Canadian Tire, you’re going to pay more for them and you’re going to have less money in your pocket. You’re going to try to conserve—like when the price of gasoline goes up, you try to drive less. And since you’re spending less money, there’s going to be fewer jobs in the rest of the economy, because there’s less money being spent. I don’t know how it can be any more obvious.

Q: People have a hard time applying that logic when their domestic industries are losing out.

A: Maybe we just have to go through a phase of deglobalization to prove it. I sincerely hope not. Especially since trade-dependent economies like Canada stand to lose the most from that trend.

READ: 23 charts to watch on inflation and the economy in 2022

Q: You extol the potential virtues of big policy shifts that are sometimes considered “politically impossible,” like introducing a guaranteed basic income.

A: When governments had the ability to take a longer-term view, such as the Mulroney government, they said, “Well, we’re going to do tax reform because that was in the Macdonald Commission, and free trade.” These kinds of things that were only going to have long-term payoffs, but very fundamental ones.

Efforts today to draw a similar consensus often founder on the debates—if not genuine economic debates. I’m a little pessimistic about the ability for politics to deliver. This world is going to be riskier and governments won’t be capable of buttressing us.

Q: One outcome you’ve floated is that companies will start taking on more of the heavy lifting even when it comes to social policy, whether that is childcare or housing co-ownership or mortgages.

A: The number one driver is the demographic shift [with baby boomers leaving the labour force]. From a workforce point of view, the next five years are quite critical. The fourth industrial revolution will be having its peak effect. That will be a window in which we have a growing shortage of workers with the skills we need at the same time that we’re disrupting a lot of other people through the development of technology.

One outlet would be a renaissance of labour unions. People could invest more in organizing themselves in order to defend or protect themselves. Most companies would say, “What can we do to avoid this?” You begin to accommodate the workers more in advance. The stresses are likely to lead to more and more solutions coming from companies.

Q: When it comes to climate change, you also seem more optimistic that investors will lead the way, rather than governments.

A: Probably only 30 or 40 per cent of emissions come from companies that are traded on the stock exchange, so the investor enforcement mechanism can’t cover everybody. But it’s very likely to through the competition effect. People are expecting it not just as investors, but as consumers.

Governments will have sporadic mandates—like you can only have this many emissions, or you can only have this many internal combustion engines—without actually optimizing what could be the most efficient and least costly route to net zero. What is more likely is that the investors will figure it out.

Q: In the book, you touch on the future geopolitics of fresh water. I would guess that that’s not top of mind for Canadian policy-makers right now, but should it be?

A: That’s a big, hard-to-put-your-arms-around risk. There’s no question that this issue will become more existential than energy. Who’s got water? You look that up and right away you come up with some key players that have a lot of water, and we’re one. A little bit of arithmetic really puts it in perspective. If you can satisfy the entire world’s daily needs from this one outflow [out of the St. Lawrence River into the Atlantic Ocean], that is an incredible endowment. That is something that, if you think strategically about it, Canada could make use of.

Poloz’s picks

His favourite books are those he fell in love with in 1967, the summer before eighth grade, when he found the sci-fi shelf at an Oshawa public library. (Click through this gallery. Interview continues below.)

Q: Speaking again about your optimism: you had a near-death experience in 2004. While on a golf course, you collapsed due to a congenital heart defect and needed to undergo major surgery. How did that change your thinking?

A: The phrase “life is short” becomes even less trite when something like that happens. I was 48 years old. I had not had a balanced life. I was very driven. Hard-working. Too hard-working. That experience definitely gave me a more balanced sense of life and it made me feel profoundly optimistic about how the world will turn out.

Your outlook should never be long-term gloomy, because, look at history. How could you be gloomy about the next 30 years when you look at the past 30 years? You could be concerned about volatility and that’s what I want people to understand better. But that’s not the same as being sad about the future. It’s just about being prepared and capitalizing on the good things.

Q: What about those first few chaotic months of 2020, before your term as Bank of Canada governor ended in June? It must have been incredibly stressful in your position, the stakes being as high as they were.

A: It was. They were. Day and night for those couple of months, there was no respite. The international meetings were at all hours of the day. I was living in our basement because I’d been going downtown to Parliament Hill and didn’t want to run the risk of exposing my spouse. It was just around-the-clock stuff.

Q: You write about taking leadership lessons from fictional characters—Jed Bartlet, the president in The West Wing, and Jean-Luc Picard, from Star Trek. What do you admire about them?

A: Writers have been quite judicious in their development of those characters, demonstrating not just how they excel but also their failings. You can watch them and think, “Oh, man, that’s a real human moment. Oh my gosh, that’s probably what I would do.”

Then you see how the team is down in the trench with the boss. Whether the world is going to end or the black hole is going to swallow the Enterprise, somebody on the team says: “Wait a minute. What if…?” And there’s Picard saying “Make it so,” relying on the team, making sure they’re in it with him all the way. They share the glory. They realize that the key is you wear your values on your sleeve.

When I did leadership work with my executive team, I asked them all to watch the first season of The West Wing and I gave them a copy of the book Make It So: Leadership Lessons From Star Trek: The Next Generation, by Wess Roberts and Bill Ross.

Q: You decided very early that you wanted to be governor of the Bank of Canada someday. What would you tell a young economist who has the same ambition today?

A: What I think helped get me here was I was always preoccupied with the real economy—people, whether they’re employees or employers, making decisions every day. That is what makes the economy what it is. So my advice to a young person would be, of course, you need to learn as much economics as you can. But you also need to save time every day just to read the news. You have this sense of constant applied economics. And it grounds you in what’s real.

This interview appears in print in the March 2022 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.