What’s in a number? For Hamed Shafia, it may mean a new trial

Michael Friscolanti on why the age of Hamed Shafia, accused in the killing of his sisters, is such a mystery—and why it matters

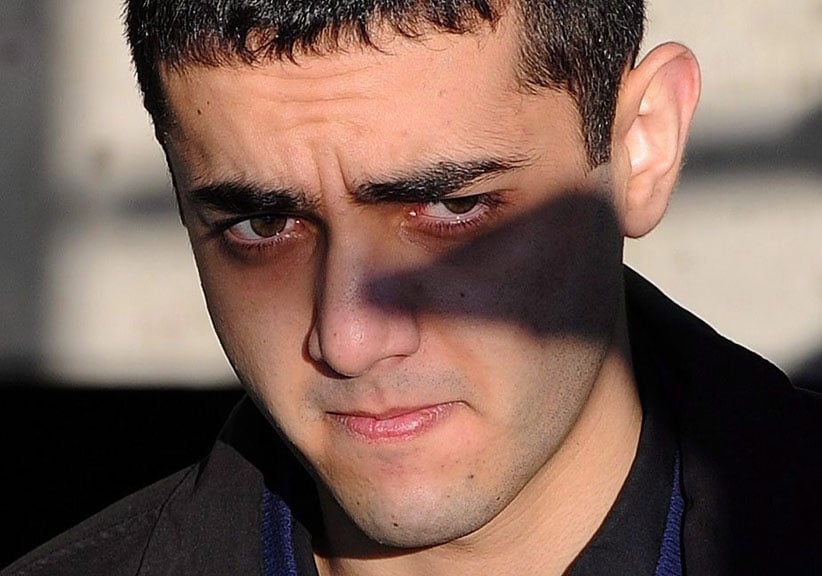

Hamed Mohammed Shafia is escorted by police officers into the Frontenac County courthouse in Kingston, Ontario on Wednesday, January 18, 2012. (Sean Kilpatrick/CP)

Share

As soon as Tooba Yahya was in handcuffs, investigators separated the accused “honour killer” from her fellow suspects (her husband and son). By design, a Farsi-speaking constable joined her in the back of the cruiser as it steered toward police headquarters in Kingston, Ont. It was July 22, 2009, less than a month after three of Tooba’s teenage daughters were found dead, floating inside a Nissan Sentra at the bottom of the Rideau Canal.

“Do you hear their voices?” the female officer asked. “Do they come to you in your dreams? What do they say to you?”

At one point, the officer asked about Tooba’s beloved son, riding in a different car with Dad.

“How old is Hamed?”

“Eighteen,” Mom said.

“How old?”

“Eighteen.”

At the time, it seemed an inconsequential question. Investigators knew exactly how old Hamed was—18, as clearly marked on all his Canadian ID—but the officer was anxious to keep Tooba talking. The more she shared about her children, the more likely she might be to admit why she helped murder three of those children (and her husband’s other wife in their polygamous family, all recent immigrants from Afghanistan).

Nearly seven years later, that throwaway question—How old was Hamed Shafia?—is suddenly a major point of contention in a sensational case that isn’t quite finished. Seeking a new trial, Hamed now insists his mother was mistaken: that he was actually 17 when his sisters died, and that he should have been tried in youth court, where sentences are lighter and parole comes more quickly. In other words, Hamed wants the Ontario Court of Appeal to believe that the woman who brought him into this world (and who worshipped the ground he walked on) was wrong all this time about his birth date—by one full year.

Is that possible? As far-fetched as it may sound, Hamed’s new story isn’t the killers’ most ludicrous claim. (That title belongs to father Mohammad, who, at trial, tried to explain what he really meant when police wiretaps caught him urging the devil to “s–t on” his daughters’ graves. “To me, it means the devil would go out and check with them in their graves,” he famously testified.)

In 2012, a jury agreed with the prosecution’s theory: that the Shafia girls (Zainab, 19; Sahar, 17; and Geeti, 13) were killed because they were, in Mohammed’s words, disobedient “whores” who tarnished the family’s honour. Rona Amir, Shafia’s infertile first bride, was a convenient throw-in, long abused by her husband and fellow wife. During the trial, no one ever disputed Hamed’s date of birth. All sides believed he was born on Dec. 31, 1990, making him 18½, an adult in the eyes of the law, at the time of the crime.

Only after the verdict did supposedly fresh evidence come to light.

Related: Michael Friscolanti’s defining longread on the Shafia killings

Staring at a life sentence with no chance of parole for 25 years, Mohammad says he wanted to transfer some of his Afghanistan property to Hamed. From prison, he asked his other son, who cannot be identified because of a permanent publication ban, to contact an overseas employee to arrange the necessary paperwork. (A multimillionaire businessman when his family moved to Montreal in 2007, the Shafia patriarch remains a very wealthy man.) In Kabul, the defence claims, the employee stumbled upon Hamed’s tazkira, the main identity document issued by the government of Afghanistan. The date of birth? Dec. 31, 1991—not Dec. 31, 1990.

According to documents filed at the Court of Appeal, the employee then obtained two other files that further confirm a 1991 birth date: a “certificate of live birth” from Afghanistan’s Ministry of Public Health, and a translation of the tazkira from the Ministry of Interior Affairs.

Addressing the province’s high court last week, Hamed’s new lawyer, Scott Hutchison, told a three-judge panel that there is a “casualness” and “diminished cultural significance” assigned to dates of birth in Afghanistan. Throw in the fact that the Shafias fled that nation’s civil war in the 1990s—moving from Pakistan to Dubai to Australia before finally arriving in Canada—and he said it’s easy to see how Hamed’s birthday could have been misstated somewhere along the way.

When it was their turn to speak, Crown lawyers described the new documents as “entirely unreliable,” especially since two other birth certificates, already on record, clearly show that Hamed was born in 1990. But here’s the biggest problem, said prosecutor Jocelyn Speyer: the three Shafia children born immediately after Hamed, including dead sister Sahar, arrived in consecutive years. If Hamed is indeed one year younger than originally assumed, so is everyone else—and that would make all their documents wrong, too.

The one person who surely knows the truth—Mom—isn’t talking anymore.