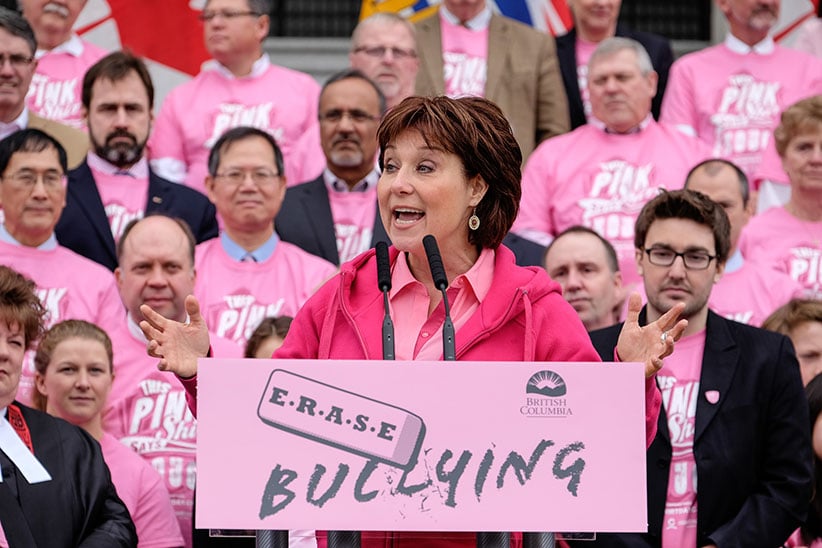

Christy Clark: The comeback kid

Her poll numbers are sinking and missteps are piling up. So how is Christy Clark still smiling—and thriving—in the ruthless world of B.C. politics?

June 19, 2015 – Vancouver, B.C., – BC Premier Christy Clark in her Vancouver office. (Photograph by Jimmy Jeong)

Share

One month ago, Christy Clark found herself in the middle of a uniquely Lotusland controversy. What began as a plan to transform Vancouver’s busy Burrard Street Bridge into a massive yoga mat for the UN’s International Yoga Day quickly devolved into a PR nightmare for the B.C. premier. The hokey branding exercise coincided with Canada’s National Aboriginal Day. Its significance this year was magnified by the sobering report on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, tabled days earlier. An unlikely cross-section of British Columbians—Indigenous activists, car-commuters, taxpayers rankled by the estimated $150,000 policing tab, Raffi—rose up in anger.

Undeterred, Clark fired off a tweet so bizarre some believed her account had been hacked: “Hey yoga haters—bet you can’t wait for international tai chi day,” it read. Attached was a photo of the smiling premier in front of a strip mall tai chi studio in Parksville. One day later Clark pulled the plug on “Om the Bridge.”

It was a sideshow, sure, and distracts from more worrying revelations from a Liberal government in its 14th year and dogged by accusations of rot and arrogance.

In May, claims emerged that Liberal staffers have been destroying internal records to circumvent Freedom of Information requests, in what appear to be flagrant abuses of the public’s right to know. The allegations came from within: a former executive assistant to a Liberal cabinet minister claims that when he resisted deleting requested emails a senior staffer grabbed his keyboard and erased them, a practice he claims is widespread.

In June, the mysterious firing of eight health ministry researchers, one of whom subsequently committed suicide, flared up for the umpteenth time when it emerged that no RCMP probe was ever conducted into their alleged privacy breach. The government’s repeated claims to the contrary were an apparent ruse, cooked up to allow them to stonewall on the botched firings. (The government has since admitted to mistakes and quietly settled several wrongful dismissal lawsuits on the taxpayers’ dime.)

Last week, it emerged that Clark’s personal approval ratings had dipped to 30 per cent, according to Angus Reid Institute polling, the third-lowest rating among premiers (after New Brunswick’s Brian Gallant and Manitoba’s Greg Selinger), suggesting even Liberal voters are unhappy with her, says the institute’s Shachi Kurl. Meanwhile, Clark has bet her legacy, and the province’s economy on liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports. The gamble could pay off handsomely, but is also risky and has yet to yield results.

“People can decide if they like me or not,” says Clark, seated in her Vancouver offices last month, and flashing her trademark, 1,000-watt smile. “That’s their choice. You can only be who you are.” B.C.’s Liberal premier is simultaneously steely and warm. She trades political gossip while checking her phone to make sure Hamish, her 13-year-old son, didn’t try to get through during her last meeting.

The following week, at a B.C.-Korea trade investment forum in a bleak, suburban Hilton, Clark captures the attention of the executive-class crowd with a quote from The Fatal Encounter, the South Korean blockbuster. Her delivery is relaxed, effortless. She is having fun.

A growing consensus among top political operatives says that Clark is the country’s most formidable retail politician. Whether it’s the aging mother of a political staffer or the daughter of an Osoyoos cherry farmer working a roadside stand, Clark has a knack for making them feel like the most important person for kilometres. Pity her security detail, though. Wherever Clark travels, someone is certain to grab her in a bear hug. Most pause mid-embrace, she says, as if thinking: “Am I allowed to hug you?”

Nevertheless, the ugly news and sinking polls have some wondering if this could be the beginning of the end for Clark. B.C., after all, is notorious for sending its leaders packing unceremoniously (e.g. Mike Harcourt, Glen Clark). But those closest to Christy Clark are unfazed. Her smile and warmth disguise a basic truth about Clark, they say: she is a master tactician. And backed up against a wall is where she is at her best.

In a way, it still feels a bit surreal to be writing about Clark at all. B.C.’s 2013 election seemed fated to be her political swan song. Instead, she authored one of the greatest political comebacks in the country’s history.

In 2011, after winning the B.C. Liberal leadership with the support of a single caucus member, Clark fought to hold the province’s centre-right together. Her party was leaking like a dog on a hydrant, to borrow Lyndon Johnson’s phrasing. Stories of caucus showdowns became routine. A series of scandals plowed over her. One hit the front pages weeks before the vote, exposing a crass, Liberal plan to exploit ethnic communities for “quick” wins. Her friends in media whispered she was a lightweight, dim even. Pollsters wrote her off. Some of the most pessimistic voices were in her own caucus, she says.

When the campaign launched in April, her Liberals were trailing the NDP by 20 points. The Vancouver Province put her opponent, NDP leader Adrian Dix, on the front page with the headline: “If this man kicked a dog, he’d still win the election.” Days before the June vote came news of the formation of a movement calling itself the “801 Club”—so named because the rush to replace Clark was slated to begin one minute after the polls closed on election day.

“It was awful,” says legendary Queen’s Park strategist Don Guy, who was imported from Ontario to head Clark’s campaign. “It was so relentlessly negative. It wasn’t just media and opinion leaders drinking their own bathwater. The bathtub was completely empty. Even the business community was cozying up to Dix.”

“We were a mutual support society,” says Don Millar, the Liberals’ in-house advertising specialist. But with Christy there was just no giving up. She grabbed the party by the lapels, and said: “We’re going to win—stick with me.”

Clark turned it around through a skilfully-waged campaign. She shrugged off internal dissent and managed to turn the focus to the economy, preying on fears of an NDP government stifling growth. Slowly but surely she chipped away at Dix’s pre-election lead. Only those closest to her will offer a hint of the private toll: “She was determined not to crumble. And not to let people see her crumble,” says Liberal president Sharon White, a lawyer and long-time friend.

Clark admits the two years heading into the election were hell: “I wasn’t going to say: ‘I can’t do this anymore because you guys are being so mean to me.’ Once I became leader it was on my shoulders. I wasn’t going to let people down. I knew that if I could make it out of that really difficult period, that I could carry the campaign on my shoulders. But I needed to make it out alive.”

On July 15, Clark will arrive at the 2015 summer meeting of Canada’s premiers in Newfoundland as one of the country’s longest-serving statespersons, and one of three powerful female premiers. In some respects, the others have followed in her footsteps: Alberta’s underestimated Rachel Notley came from behind in a similarly unprecedented victory. Ontario’s Kathleen Wynne is a politician who shares Clark’s retail skills.

For Clark, gender was an early issue. There’s a fine line between confidence and arrogance—a constant knock against Clark—and in politics as in business, which one you are labelled often depends on your gender. But some of the sexism Clark has faced has been less subtle—being asked on radio what it is like to be a MILF, for example. A column pinning her unpopularity to her gender. A TV spot analyzing her wardrobe. Another on her hair. An invite from Richard Branson, the Virgin CEO, to kitesurf naked on his back. The controversy that erupted when she wore a V-neck to question period—too much “cleavage,” according to an opposition MLA. Being asked how she planned to balance her role as a mom with the responsibilities of office. “Stephen Harper manages to go home for dinner with his kids every night—and he’s a pretty busy guy,” Clark replied. “My son is no longer a toddler. We can handle it.”

Liberal insiders admit the party—long a downtown, businessmen’s club—was “a man’s, man’s, man’s party,” says Simon Fraser University management professor Mark Wexler, who specializes in leadership. They had a tough time adjusting to taking marching orders from a woman. “For the Liberals,” Wexler adds, “she was revolutionary.”

Clark has never let the sexist “noise” get to her, says Laura Miller, the party’s executive director. “But she understands the importance of her role: that she is blazing a trail, that she’s got a responsibility to women, and to young women particularly, that this will get easier over time.” Recalling the difficulty in finding her footing as a young woman, Clark’s advice is simple: “Be who you are. Some people won’t like you. But lots of people will be glad that you’re authentic.”

Clark is in some ways an anomaly. She doesn’t have a university degree. She is divorced, and a single parent in an era when most politicians are lawyers, highly educated, often male. Behind the scenes, hard-working spouses ensure their kids are fed and ferried. Rachel Notley’s husband, Lou Arab, joked recently on Facebook of becoming “purse-holder-in-chief” for Alberta. Clark has none of that. Her relationship with Mark Marissen, her ex-husband, is strong enough that he continues to advise her. And while they co-parent Hamish, those closest to her say the premier has at times carried more than her share of the load.

Whether strategic or not, it has helped her connect with voters who feel similarly. At a recent women’s networking event in Vancouver, she began her speech with an apology: she couldn’t stay beyond her speech because Hamish needed help with a school project. Everyone there understood the duelling demands.

Many politicians shield their children from the public glare. Clark takes the opposite approach: she constantly mentions her sensitive, blue-eyed boy, a hockey goalie and sports nut. After a big win, he is her go-to for a hug. “Hamish,” she says, “is the most important thing in my life, and he always will be.”

He attends Vancouver’s top, private boys’ school (with tuition between $18,995 and $21,355 per year) where he’ll enter Grade 9 this fall. She is raising him in a duplex on Vancouver’s West Side. Over wine, her girlfriends say, Clark is the same person seen on the stump: fun to be with, smart, lively, thoughtful, kind, a quality she is determined to impart to Hamish. It helps explain their unlikely winter holiday: Last Boxing Day, they flew to New Delhi to help build a school in northern India.

Clark inherited her political drive from her dad, Jim, a high school guidance counsellor known for his deep political convictions. The Liberal diehard ran provincially for the party three times, in 1966, ’69 and ’75, losing all three, back when the party was reduced to a handful of seats.

Mavis, Clark’s mom, was a force in her own right. She left her job as a hospital dietitian to raise her four children but managed to study art and founded Burnaby’s first non-profit daycare. When Clark was 12, her parents split up; Mavis had begun graduate studies, and became a counsellor and co-founder of the Burnaby Family Life Institute.

The teenage Clark was a dynamo: “She used to come to school just to argue with me,” recalls Fred Lepkin, who taught her history at Burnaby South Secondary School. “She was always witty, to the point and engaging,” her English teacher, Steve Bailey, recalls.

When she enrolled at Simon Fraser University in the mid-’80s, after travelling in Europe as a nanny, “Berkeley North” had shed its radical roots. Student government, however, was unchanged, “run by the same old cabal of radicals,” says Andy Tomec, who wrote for the campus paper, The Peak.

Even then, Clark, the fiercely partisan, chain-smoking head of the campus Young Liberals, delighted in getting under their skin: “She knew how to work the media and had a great sense of humour, but always in service of a political agenda: taking her political enemies down a peg, or decrying the many foibles of fellow student politicians, the NDP, or loopy left-wingers in general,” Tomec recalls.

School was never the priority. Clark, whose black, Nana Mouskouri glasses poked out from beneath her blond mop, used her time at SFU to make connections: people who would go on to become movers and shakers in Vancouver, including developer Ryan Beedie, B.C. Liberal operative Mike McDonald, former finance minister Kevin Falcon and Marissen, a visiting student from Carleton who went on to become a legendary Liberal organizer. Among them, Clark stood out, McDonald says. “It’s mainly guys who get involved in politics. She put her elbows up, and came in saying, ‘I want a spot at the table.’ ”

After a year as the student council’s lone right-winger, Clark took a run for president, appalled that the governing slate was diverting fees, ostensibly collected to provide student services, to support labour groups and Central American causes. The campaign was “brilliant—not that anyone was paying any attention,” says Tomec. “She mobilized supporters, spoke with passion, debated with take-no-prisoners bravado and got enough people angry enough to actually vote.” Clark won by six votes, but her victory was quashed: she’d forgotten to remove a couple of posters at a downtown campus and was late paying the $60 fine.

Clark joked to The Peak that she’d considered selling her car to hire a lawyer, but even with “a full tank of gas and a couple of textbooks in the back” it wasn’t worth more than $100. She left SFU soon after, never completing her degree. Six years later she was elected to the provincial legislature: a highly polarized theatre that mirrored the campus dynamic, with many of the same players.

First, she honed her skills as a strategist. “Whether she was brilliant, or just plain lucky,” says Tomec, “we’ll never know. But Christy got in on the ground floor with the Liberals, and after that it was a high-speed elevator ride straight to the top.”

She made a name for herself during the B.C. Liberals’ 1991 campaign. The party was in shambles: broke and disorganized. Clark, then 25, crisscrossed B.C. with McDonald in a borrowed, Chrysler van. Their mission: to sign up a Liberal candidate in every riding. Picnic table, pub, hot tub, they met with potential candidates wherever they could. “Christy was the closer. She’s always had that ability to win people over,” says McDonald.

The election was a watershed for the Liberals, who formed the official Opposition to Mike Harcourt’s NDP, “due in no small measure to Christy’s persistence,” says Clive Tanner, the Victoria Liberal stalwart who’d loaned the pair his van.

In 1993, Clark moved to Ottawa to head the federal Liberals’ scrappy youth wing with Marissen. There, she caught the eye of the B.C. Liberals’ new leader after hosting a party for him. Gordon Campbell recruited her to run for the Liberals provincially in Port Moody-Burnaby Mountain. Clark moved home with her mom, spent a year on the stump and picked off the riding from the NDP, winning by 468 votes.

Jim, the old Liberal warhorse, didn’t live to see his daughter, then 30, take her seat. Mid-campaign, he died of a heart attack. He’d been a smoker, and had a drinking problem. Clark was “acutely conscious” of her dad’s flaws, she once said; and his death caused her to reflect on her own lifestyle. Six months later, Clark dropped her own two-pack-a-day habit, the first step in a personal transformation, according to McDonald: “She started running and lost a significant amount of weight. She took pains to become a better public speaker. She became focused and aggressive in question period.” Clark, who’d married Marissen on Galiano Island, emerged as an acid-tongued Liberal live wire.

“Nobody can drive an NDP cabinet minister into a trembling, voice-cracking rage quite like Christy Clark,” the Vancouver Province wrote of her in 1999, in her first major newspaper profile. Clark emerged as Campbell’s scrappy lieutenant. That dynamic would eventually undo them—there wasn’t room enough for both egos in Victoria—but in the late ’90s, their one-two punch eviscerated a scandal-weakened NDP.

In May 2001, the Liberals captured all but two of the B.C. legislature’s 79 seats, forming government for the first time in 50 years. Three months later, Clark gave birth to a son, Hamish; she became only the second female cabinet member to have a child while serving in cabinet, after Quebec’s Pauline Marois. Clark was back at work 33 days after giving birth, facing repeated questions over how she could balance the job with her role as a mom. “The House is sitting,” she replied. “I can’t not be here.”

Campbell named Clark education minister and deputy premier. Storage space across the corridor from her legislative office was refashioned as a nursery. The NDP cut her no slack, accusing Clark of accepting a taxpayer-funded nursery “while the government was cutting back on child care benefits for the rest of B.C. parents.” (Clark was in fact paying out-of-pocket for the wall hangings, the carpet and the nanny.)

She would soon give the NDP legitimate reasons to attack. She went to war with the teacher’s union, overhauling the B.C. Teacher’s Federation. She oversaw the closure of 91 schools, delivering marching orders to aggrieved school trustees: quit whining and get on with it.

But in 2004, Campbell shunted his deputy to the children and families’ ministry, known for swallowing careers in foster-care scandals and child death tragedies, a curious demotion for his most able minister. Clark’s thrive-on-challenge bravura couldn’t offset talk of a rift—a pre-emptive move to clip the wings of a potential rival. Nine months later Clark announced her resignation, to spend more time with Hamish, then 3, she said.

Within months, Clark was equating quitting politics with leaving a boyfriend: “In the first six months you still remember all the reasons you left. Down the road you’re sitting alone at night, maybe into a glass of wine, and you’re thinking, ‘God, that guy was great! I miss him so much!’ And you pick up the phone and dial.” Four weeks later, Clark announced her bid for the Non-Partisan Association nomination for mayor of Vancouver.

Her late start proved fatal: She lost by 64 votes to Sam Sullivan. She may have also underestimated her soft-spoken opponent.

In between, she’d begun guest-hosting on CKNW, one of B.C.’s top news outlets, learning radio on the job. In 2007, CKNW offered her its 12:30 to 3:30 weekday slot, then-languishing at No. 6 in the ratings. Expectations were low. Yet within months, the caller-driven Christy Clark Show held the top spot in Vancouver’s afternoon radio market, and in 2008, Clark was awarded the national Peter Gzowski Award.

Clark’s six years behind the mic fine-tuned her communication skills: She learned to speak to—not at—her audience, how to draw them in, to pull at their heartstrings. She says she also learned the importance of authenticity: “You’re talking directly to people. They can hear falseness in your voice. The day I decided to seek the leadership I said: Only if I get to be me. Not some version of me. Not what people expect or want me to be. But who I really am.”

Clark had also figured out the secret to a good story: detail. Back on the stump in 2013, she brought her key policy planks to life through vivid examples, anchoring her campaign in her middle-class values.

She would run the province the way Jim and Mavis had raised her, she promised: never overspending, always living within her means. She described her modest, childhood home near the Oakalla prison in suburban Burnaby, the family’s blue Dodge Rambler. Her dad, she noted, had not only made sure his debts were cleared and the house was mortgage-free before he died; he’d even pre-paid his funeral expenses. She’d govern the same way. By reaping LNG’s riches, she said, B.C. could leave future generations better off. That narrative clinched her an election she stood no statistical chance of winning.

Out of the spotlight, Clark had also done a lot of growing up: she split with Marissen and moved to Vancouver. A few months later, in December 2005, Clark’s mother was diagnosed with brain cancer. Clark would wake at four every morning, to go to the hospital to brush her mom’s teeth and help her shower. The disease had robbed her mother of her short-term memory. Every day, returning to the hospital from work, Clark announced to her mom that she’d quit politics. “That’s the best news in the world!” Mavis would exclaim. “It was then,” Clark says “that I realized the depth of my mother’s antipathy for the business. She couldn’t cope with unkindness.”

Eventually, Clark brought Mavis to her home, and nursed her through the worst of the illness. When her mom would scream from pain and fear, disoriented by a disease that was slowly eating away her brain, Clark would crawl into bed beside her and hold her, soothing her like a child. Mavis died on March 19, 2006.

Critics describe Clark as a gifted tactician without a larger vision. Her skills are not in governance, says SFU’s Wexler, they are in campaigning.

Michele Cadario, a friend of two decades and her deputy chief of staff, bristles at the description: “I’ve never worked with a politician so clear in the direction she is moving us. She’s made liquefied natural gas part of the provincial lexicon. When before did you ever hear the term LNG?”

The Clark government also brought in one of the most progressive social programs in the country this year: it allows single parents on welfare to return to school tuition-free. The government will also cover child care and transportation for a year while they train for an “in-demand” occupation.

But it is still far from clear that B.C. is on the brink of anything. In Asia, the price of liquefied natural gas hit record lows this month, a sign that supplies of the energy source have already caught up with demand. Clark has relentlessly touted B.C. LNG—fuel that is super-cooled to liquid form for trans-ocean shipping—as B.C.’s ticket to economic prosperity, a scheme valued at $1 trillion ahead of the last election. Tellingly, pledges to use royalty revenue to erase a debt nearing $70 billion appear to have vanished from her talking points.

“If you set your goals low you’re guaranteed to meet them,” says Clark, shrugging off concerns that LNG projections have been too sunny. “People aren’t depending on me to sit around and say how bad it is. People are depending on me to set big goals and drive as hard as we can to get to them. I’ve said we want to have three LNG plants up and running by 2020. I think we can do that. The market is unpredictable—we don’t control that, obviously. But what I see is India, China, moving to cleaner sources of fuel.”

Clark’s dream began to feel a bit less fantastical this week: On July 13 the B.C. legislature is set to be recalled for a rare, summer sitting to clear the way for a $36-billion LNG facility on Lelu Island, just south of Prince Rupert. MLAs are set to debate a bill that would ratify a project development agreement between B.C. and Pacific NorthWest LNG, the Canadian subsidiary of Malaysian oil giant Petronas. The proposed liquefaction plant would transfer natural gas from northeastern B.C. onto freighters bound for Asian markets, and could bring B.C. $7.7 billion in royalties, according to government bureaucrats. If it goes ahead, experts say, it could be the biggest news for Canada’s energy sector since Alberta’s oil sands boom.

That’s a big “if,” but Lindsay Meredith, who teaches strategic marketing at SFU, believes Clark’s strategy is sound: “Clearly, this is where the market is headed. Japan, which turned to LNG since shutting down dozens of nuclear reactors, now imports one-third of the world’s LNG. The Chinese are choking to death on fossil fuel and Wyoming coal. You can bet your ass it’s cleaner than tar sands oil. Until everyone is willing to shut off the lights and live in the dark, we should be doing everything we can to burn cleaner energy. Plus, development of the resource would create a whack of new, taxable revenue and a need for massive new infrastructure, which fuels job growth.”

But unless impacted Indigenous communities can be brought onside, the projects could be tied up in the courts, further stalling projects in B.C. The Lax Kw’alaams Nation’s vote, last month, to reject a $1.15-billion deal to build the proposed plant on their traditional territories over concerns about the impact on the Flora Bank, a salmon habitat adjacent the terminal site, dealt the industry a troubling blow.

Given the premier’s focus on LNG and the need to involve First Nations in the process—reiterated, yet again, in a unanimous Supreme Court of Canada ruling last summer over Aboriginal rights and title—you might assume Clark is kept up at night worrying about improving relations. But critics say her government has dropped its focus on reconciliation, championed by Clark’s predecessor, Gordon Campbell: “Clark is leaving it to industry to deal with individual nations when First Nations need to be involved and included in decision-making processes at all levels,” says Michelle Corfield, former vice-president of the Nuu-Chah-Nulth Tribal Council.

Analysts are equally pessimistic about relations with neighbouring Alberta, one of the toughest files Clark has faced. NDP Premier Rachel Notley will be Clark’s fifth partner in Edmonton. The two worked cross-aisle in the B.C. legislature in the late ’90s: Clark as an opposition MLA, Notley as a ministerial aide. “It remains to be seen how much we will agree on,” Clark says. “I’m hopeful.”

Look beyond the obvious—the ideological differences and the rocky past—and a different portrait emerges. Notley says she opposes Enbridge’s Northern Gateway Pipeline, but will lobby for Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain enlargement. That stance more or less lines up with Clark’s, which may ease some of the tension that defined relations with former premier Alison Redford.

And with a bit of context, Clark’s approval ratings, which sparked a flurry of nasty headlines on a slow, summer news week, look a bit less ugly. The B.C. electorate is an intensely polarized, curmudgeonly bunch. Within two years of Gordon Campbell’s colossal majority his popularity had plummeted to 28 per cent. Mike Harcourt fared even worse: at the mid-point of his first mandate, the NDP premier’s approval ratings were 23 per cent. And Clark, after all, has come back from worse.

There’s no secret to it, she says. “You pick up your foot, and you put it in front of the other. Sometimes you don’t know where the exit sign is, but you know that if you don’t keep moving you’re never going to get there.” She recalls the advice former Ontario premier Dalton McGuinty gave her ahead of the 2013 election: “The minute you get off that bus it’s all on you. So don’t mess up. Be disciplined, remember what you stand for and don’t get thrown off-course.” McGuinty had a final piece of advice. “You’ve got a great smile, Christy,” he said. “Use it.”