How to get bills paid on Parliament Hill

Sometimes you have to get creative, Duffy’s trial hears

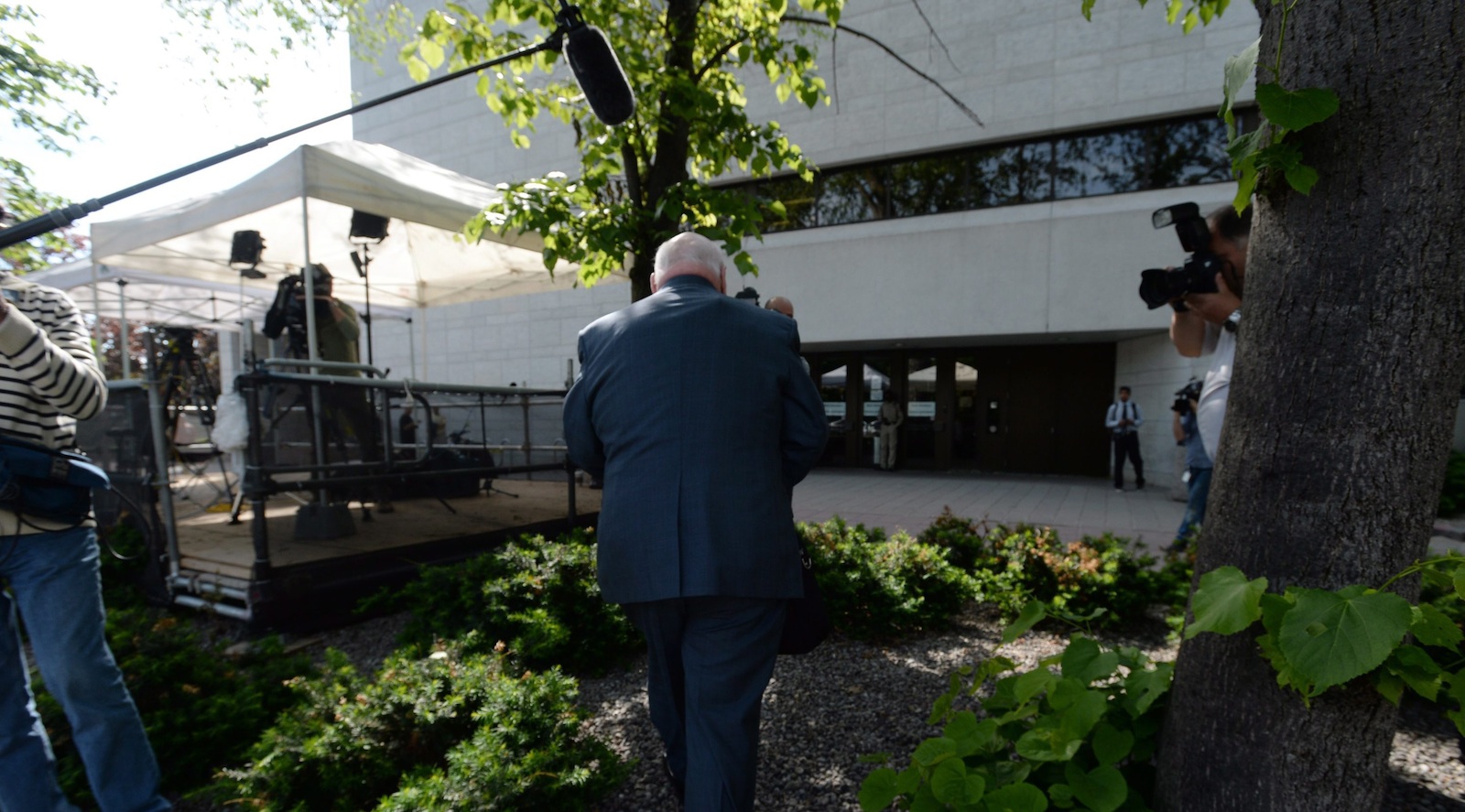

Suspened Senator Mike Duffy arrives at court in Ottawa on Thursday, June 4, 2015. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick

Share

In what is a fascinating indication of the knotted, tangled nature of large sprawling legal matters in small political towns like Ottawa, it emerged today that three Crown witnesses in the trial of suspended Sen. Mike Duffy are represented by the same lawyer.

What’s more, that lawyer, James Foord, got his start in criminal law articling for Bayne Sellar Boxall, the very firm in which Duffy’s lawyer, Donald Bayne, is a partner.

Details of Foord’s role in the case came out in court this morning, after a break in the proceedings, when Bayne stood to address Justice Charles Vaillancourt on the topic of Gerald Donohue, whose appearance as a witness has thus far been delayed due to bad health.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Mike Duffy”]

Donohue has been much mentioned in this court because of a series of Senate contracts he received from Duffy. Court has also seen numerous cheques Donohue cut in order to cover a number of Duffy’s expenses. Prosecutors say Duffy funnelled public funds through private companies linked to Donohue in order to skirt Senate rules.

Bayne introduced Foord as Donohue’s lawyer. Foord stood and bowed—a tall, blond, square-jawed man—and Bayne went on to relay Foord’s update on Donohue: that he is enjoying better health, and may soon be in a position to give testimony in Courtroom 33, where Duffy is on trial for 31 charges of fraud, breach of trust and bribery.

Just then Mark Holmes, the lead Crown in the Duffy case, shot to his feet to observe that prosecutors would prefer, against the likely wishes of Bayne, to get Nicole Proulx, former head of Senate finance and Duffy’s numero-uno nemesis, back in the witness box.

Proulx’s testimony was put on hold back in April, pending a decision on the admissibility of a certain Senate document, which Vaillancourt has since allowed.

Then Holmes unfurled, in an offhand parenthetical way that in courtrooms often exposes those storms of intrigue otherwise concealed from spectators, Foord’s relationship with two other witnesses called by the Crown—Melanie Mercer, Duffy’s former executive assistant, whose testimony ended yesterday, and Diane Scharf, another Duffy EA, who just then was sitting amid all the hubbub, right there in the witness box next to the judge.

It is not the norm for witnesses to arrive in court with counsel, though in fairness this is just the sort of high-profile case where you might expect to see that happen. It’s also the nature of trials for witnesses to choose sides, and it’s likely we’re seeing something of that sort here as well.

The connection between Foord and Bayne—the latter being one of the top two or three defence lawyers in this city—has much to do with how small Ottawa is, and probably too with how promising a student Foord was in 1996, when he began articling with Bayne’s firm; Foord remained there for five years (this according to a 2006 Ottawa Citizen news story detailing a County of Carleton Law Association award Foord received that year for the excellence of his service to clients).

Scharf, the Duffy EA, did not deliver testimony altogether friendly to the Crown’s case today, and Bayne objected to prosecutor Jason Neubauer treating his time with her like a cross-examination.

We’ll look at her anon.

Neither did Mercer do the Crown many favours. She described her early training in the Senate, under the guidance of executive assistants that higher-ups assigned her to shadow, as including direction to keep on hand stacks of pre-certified travel expense claim forms she could use in a pinch to meet the Senate’s stiff deadlines.

Improperly claimed travel expenses are a mainstay of the Crown’s allegations against Duffy. Mercer’s evidence would suggest his weren’t out of the norm.

The value to the Crown of Donohue’s testimony has, of course, yet to be established.

Meanwhile, Scharf provided court with a lively, mercifully short, day of testimony.

Top of mind for Neubauer was the cellphone plan Scharf entered into while working in Duffy’s office, and which she says he arranged to pay for through a Donohue-family company.

Under Senate rules, senators are permitted four cellphone plans, and Duffy had already reached his limit by the time Scharf arrived. Neubauer walked Scharf through the cheques, issued by Ottawa ICF and signed by Donohue, which Scharf cashed to pay off the BlackBerry.

Scharf is a sprightly woman with 42 years of experience working on the Hill. She had been with cabinet minister Rona Ambrose’s office in the House of Commons until shortly before joining Duffy’s office in the Senate. She went on after her time with Duffy to work with two more Tory senators.

She repeated her position, from the previous day, that the Donohue cheques were not an attempt to circumvent Senate rules, just merely a way to get her the cellphone she needed to do her job.

“We were trying to serve the public and get legitimate bills paid,” she said.

On this, Scharf, her black eyes alive and penetrating, was adamant.

Neubauer, who favours an understated approach to quizzing witnesses with outlandish things to say, asked her whether she didn’t think it funny that someone outside the Senate was paying.

“Whose money did you understand was being provided to you?” is how he put it.

“I’m quite accustomed to this,” said Scharf, repeating that she’d seen similar arrangements elsewhere on the Hill. “You have to be creative a bit sometimes to get bills paid.”

As she did yesterday, Scharf charmed the court with her forthright answers and exquisite use of quotidian language.

When Bayne, during cross-examination, asked her whether she connected the service contracts awarded Donohue with the money she received from him reimbursing her for her cellphone, she fairly bristled.

“I didn’t make the correlation,” she said. “I had no idea what he did with that money. He could have put it in his pocket … maybe the money for my cellphone came from him for selling tomatoes at end of his laneway. I had no idea and I didn’t care. I had a job to do, I needed that cellphone, and he was there ready to reimburse me.

“It was just a simple matter for a small amount of money.”

Elsewhere, Scharf told court just how commonplace she believes these schemes to be on Parliament Hill: “That’s how things like that happen, and they have up there for a hundred years—it’s sort of a backdoor way of getting things done.”

When Neubauer asked her about a certain signature at the bottom of a Senate document, Scharf reacted again with steely playfulness—some indication, perhaps, that she has difficulty suffering fools.

She couldn’t tell if that signature was generated “with a machine or a stamp or a cat’s paw,” she told court.

Describing her relationship with the Senate finance office, which sent the travel expense claim forms she prepared for Duffy back to her festooned with maddening, unintelligible corrections, Scharf told Neubauer:

“I had great difficulty understanding the Senate finance office and the way they did things … it was almost different every week.”

Neubauer was then at pains to demonstrate that the changes Senate finance officials made to Scharf’s forms corresponded with perfectly reasonable corrections. Neubauer saw those interventions as evidence that officials did police senators and their staff, providing the oversight the defence argues didn’t exist.

Bayne calls these efforts “boilerplate.”

Later, just to be sure, Bayne asked Scharf whether she ever set out to defraud the Senate.

“Heaven’s no,” she said. “Heaven, heaven, heaven’s no.”

This caused a number of unsuccessful attempts to suppress laughter in the courtroom. She was so earnest.

When Vaillancourt invited her to step out during an objection, Scharf told him: “One more time, find my shoes, exit stage one.”

It was the end of her performance.

Tomorrow, we have an esoteric argument on Senate privilege to look forward to. Scharf will be missed then, above all. But—who knows?—we may learn more about either the defence, or the Crown’s, plans for auditor general Michael Ferguson’s Senate audit, and whether either side wants it admitted as evidence.

Court reporter Nicholas Köhler on the Duffy trial

- Day 1: Mike Duffy talked for a living. On Monday, he spoke six words.

- Day 2: Kafka meets Frank Capra in Courtroom 33

- Day 3: The PM is just a girl he used to know

- Day 4: The subject of honour and the genie of Cavendish

- Day 5: Mike Duffy, patron saint of the good ol’ days

- Day 6: Oversight in Canada’s Senate? There’s no such thing.

- Day 7: Plucking the wings off a visitor from fairyland

- Day 8: The Genie of Cavendish, raining contracts like manna

- Day 9: All the Senate’s a Hollywood soundstage

- Day 10: Ottawa stitches Canada together. Mike Duffy did his part.

- Day 11: The mysterious #duffytrial comes briefly into focus

- Day 12: Nicole Proulx muddies #duffytrial with clarity

- Day 13: Hubris in Courtroom 33. Wait, never mind, it’s gone…

- Day 14: The unfilmable drama: Duffy’s defence takes on a Senate staffer

- Day 15: Courtroom 33 isn’t just another Senate committee

- Day 16: A pox upon this unshakable, inexplicable Senate

- Day 17: A gothic novel plays out in Courtroom 33

- Day 18: Donald Bayne relishes the boredom of his stage

- Day 19: Snippets of human drama, portals into a great unwritten novel

- Day 20: The flare that snagged Donald Bayne

- Day 21: ‘Why not cover a real trial?’

- Day 22: An improper brand of magnanimity

- Day 23: A judge asks for busywork amid a Duffy trial standstill

- Day 24: A rogues’ gallery marches through an otherwise grey day

- Day 25: A father and son enliven the holy ghost of the Mike Duffy trial

- Day 26: The Mike Duffy Tour of Canada

- Day 27: The Mike Duffy trial stays too long at the fair

- Day 28: Mercer the Guileless takes the stand

- Day 29: A veteran assistant on the Hill: Duffy’s latest collateral damage?