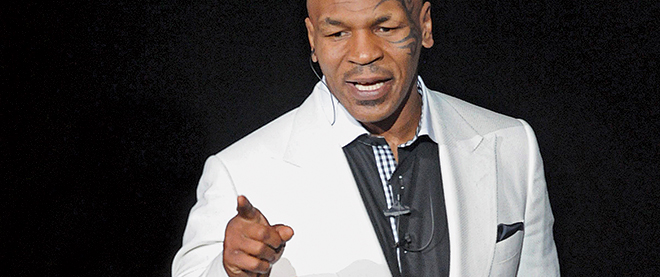

Mike Tyson on being the hyper-scary guy and what he thinks of Mayor Rob Ford

In conversation with Brian Bethune

Rex Features/CP

Share

At 47, and long out of the ring, Mike Tyson is almost as famous—and infamous—as he was in his heyday. Becoming the youngest champion in boxing history at age 20, Tyson won his first 19 pro bouts by knockout, 12 of them in the first round, and successfully defended his title nine times. He was also convicted of rape in 1992 and disqualified in a 1997 match for biting off a piece of his opponent’s ear. Throughout, Tyson was addicted, by his own account, to cocaine, booze and sex. By 2003, despite earning over $300 million, he was bankrupt. Since then, rehab and a successful marriage have sparked Tyson’s rebirth as an actor, especially in his one-man stage show, The Undisputed Truth, and now as co-author with Larry Sloman of a no-holds-barred memoir of the same name.

Q: You have a stage show, you’re on TV, a book: You’re constantly looking at your life in front of everyone. Why?

A: Well, that’s just who I am and what I am. If I to do a stage show, with a big screen, it’s because I guess people think I’m a notable guy. That’s want I want to do. I love entertaining people. That’s what links boxing and acting. I loved it when I was fighting and now that I’m fighting no more, I still want to do it.

Q: Does opening your life up in such a raw way help you look at yourself?

A: No, I’ve always self-analyzed my life. I do that every day. Now I’ve made a career out of it. As Larry and I were talking I started realizing the situation—“When this happened I was seven, I was thinking this and this.” That’s just the way I am. I can’t remember anything that happened yesterday. But I remember everything that happened 100 years ago.

Q: Is the book different than the stage show?

A: The stage show is 90 minutes and the book is 600 pages, so there’s a lot going on there. Things that I can’t say on stage I elaborate in the book. It’s very raw but I think it’s done very articulately. It’s really good, a really in-depth perspective of myself. I’m pleased with the way it came out. When people read this book they’re not going to be envious or jealous of my life.

Q: You write about how a lot of injustice landed on you. Was Desiree Washington and the rape conviction the worst for you?

A: It’s a lot of stuff. It’s my life. The way I lived my life, the way my family lived theirs, their selfishness, my whole barometer, the way I was born and came into this world.

Q: But why open with the rape trial, the middle of your story?

A: Larry did that. I gave him the information, I told him everything and he put it in that perspective. I have no idea why.

Q: Then you go back to your childhood and say [the Brooklyn neighbourhood of] Brownsville is what made you.

A: I was dealing with the reality that this is who I am. Mostly people who come from my neighbourhood are statistics, like a lot of my friends. It was just a dog-eat-dog world. That’s how it was. Learning to steal and fight at a young age, I was in a lot of trouble. But then I met Mr. D’Amato [teenaged Tyson’s boxing manager] and that changed.

Q: There’s a harrowing childhood memory you record, when your mother dumped boiling water on her boyfriend. You wrote about that at some length, especially that afterwards he went out and bought her some liquor . . .

A: . . . and cigarettes.

Q: . . . meaning that he had rewarded her for it: “That’s why I was so sexually dysfunctional.”

A: Hey, I never said that. I said I was relationship dysfunctional because of that.

Q: You met Cus D’Amato when you were 12 and right away he was telling you you’d be champion of the world.

A: He told me I’d be the youngest champion ever if I listened to him, have all the money in the world, all the women in the world and “no” would be a foreign language to me.

Q: Did he see something in you or did he create it in you?

A: Let me tell you something, man: I haven’t the slightest idea. It’s the only part of my life that I’m really lost about, right there. I mean how the hell did he know? I was getting shellacked in the ring, I was getting the shit kicked out of me. And he was saying all these great things. He was happy. But he wanted to make sure I’d say I was 13, lie about my age because I was muscular and tough. I had a strong desire to learn and I did rapidly and he was just orgasmic about it. People used to tell him about me, “He ain’t gonna make it, he’s too small,” and Cus used to say, “This guy’s a monster. You watch, he’s gonna reign forever.” He used to say so many nice things about me, I thought he was a pervert. No one ever said nice things about me; I didn’t know how to take it. Professional trainers would say those disparaging things about me and Cus would get so angry. He’d just say to them, “You don’t know. This is going to be the next heavyweight champion, the youngest ever. If he listens to me.”

Q: So you don’t know if he saw the ferocity in you or if he made it, then?

A: All I know is that he wanted that ferocity, that meanness, that intimidation. He wanted me to make the other guy believe I wanted to kill him.

Q: What do you make of D’Amato now? Sometimes you make him sound like he’s the most amazing guy you ever met and other times you say, “Cus f–ked with my mind.”

A: Listen, he dealt with me with the best life skills he had. He loved all types of history. He was a walking encyclopedia; he equated psychology with boxing. He would use Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Twain, Hemingway and explain the psychology of their work to me and how it applied to boxing. Cus had been dumped on by life, too. And he wanted his champion. I’ll tell you what, though, the best thing that ever happened to me was [that] I met him. No doubt about that. I wouldn’t want it any way else. He f–ked with my mind because he knew I was insecure, low self-esteem and I had a lot of doubts. He would feed my ego with the idea of greatness.

Q: If you were the same kid now, would you go into boxing or mixed martial arts?

A: It depends who had a hold of me, looking after my interests. Maybe I would have been a teacher. Maybe I would have been a doctor like my brother. I don’t know, it depends who held my interests. Maybe I’d find being a gangster interesting if I was kid again.

Q: You write that martial arts fighting is more popular now than boxing because there’s more passion in it.

A: Not necessarily the passion, but because people got tired of seeing bad decisions in boxing. Now when we see a boxing match, we know who’s gonna win before they start. Very rarely do they have evenly matched boxers. And the promoters use only their own fighters to fight each other. That’s almost like a slave contract. Instead of letting the best fighters fight each other. That’s why people don’t want to watch it no more. [UFC president] Dana White has got it right. He’s got all the best fighters fighting each other, you know what I mean?

Q: Does boxing have a future?

A: Floyd Mayweather is breaking financial records but he’s the only one. Listen, how much money did Andre Ward make? He’s the second-most powerful fighter in the world, and what did he win? Did he make even $2 million dollars defending his title? And if he did that, it must have been his highest purse. It’s gone from $47 million to $2 million for No. 2s. There’s such a financial gap between No. 1 and 2, it’s like the sun to Mars.

Q: How often were you playing a role as champion? The hyper-scary black guy?

A: That’s who I was and who I wanted to be. As a young kid, I used to watch boxing films and I would stop the film when I’d see something I liked—the way he bowed, the way he’d hit somebody or the way he stood with his belt—and I would rewind it and I would emulate it. Over and over again. I liked the villains best because you never forgot them.

Q: Your aim in this was fame?

A: Prosperity, glory.

Q: Have you heard about Toronto’s mayor, our crack-smoking Rob Ford? Is that behaviour you recall from yourself or friends?

A: I never did crack but when you do that stuff I’m sure you’re totally insane for that moment. When he was up there ranting and raving and punching and all that “take me on” stuff, like they say, drugs make who you are, make you uninhibited. The truth comes out. And that’s who he truly was. There may be others in the same situation, but maybe they don’t have the same courage as he did, putting it out there and being bare, emotionally naked like he has.

Q: You’ve always been fascinated by pigeons. What do you love about them?

A: It’s like someone who raises horses or dogs. I’ll always have birds, until the day I die. I have a couple thousand in New York, Brooklyn, but I have like 70 eggs here in Vegas. Some of them race and some of them fly free.

Q: You had so many stabs at rehab before it began working, albeit with relapses, in 2007. What made the difference?

A: I’m just more present now. More present for my children, more present for my family. I’m present for myself. Slips do get me down but it doesn’t have to be the way it is. It doesn’t have to be my relapse. Just got to get up, dust myself off, keep striving. Try again.