The results of the next federal election—if electoral reform had happened

Philippe J. Fournier: A new 338 Canada projection shows that under a proportional representation system the Greens and NDP would take a combined 90 seats

Green Party of Canada leader Elizabeth May introduces newly elected Green MP, Paul Manly, on Parliament Hill on Friday, May 10, 2019. (Sean Kilpatrick/CP)

Share

Proponents of electoral reform couldn’t help but reiterate their displeasure with the current first-past-the-post (FPTP) system when commenting on last week’s 338-seat projection, and the numbers certainly suggested they may have a point.

The Conservative Party of Canada, then with an average support of 36.6 per cent of Canadian voters according to the latest poll aggregate, was projected to win an average of 174 seats—just above the 170 seat threshold for a majority at the House of Commons.

“A majority government with less than 37 per cent of the vote?” many of them rhetorically asked, not without disdain.

Not since the Progressive Conservatives of Brian Mulroney in 1984 has a federal party won an actual majority of the popular vote in Canada. It received 50.03 per cent of the popular vote en route to the largest ever majority in the House of Commons (211 seats out of 282). From 1993 to 2003, Jean Chrétien led the Liberals to three straight majorities, none of them with higher than 42 per cent of the popular vote.

Since the turn of the century, neither of the two latest majority governments (Harper’s Conservatives in 2011 and Trudeau’s Liberals in 2015) even cracked the 40-per-cent mark.

Given the current fragmentation of the electorate and the rise of smaller parties—about a third of Canadians are projected to vote for another party than the Liberals or Conservatives—it is increasingly difficult to imagine any party of whichever colour win more than half the votes in any given general election.

Which brings to us to the complex topic of electoral reform.

Justin Trudeau made it a campaign promise in 2015 that “this election will be the last contested in first-past-the-post.” In the months that followed the election, it became clear that a consensus among the main parties in Ottawa was unattainable; the Liberals seemed focused on ranked ballots, the NDP and Greens favoured proportional representation, and the Conservatives were insistent on keeping the current FPTP system. Without even a glimmer of consensus on the horizon, electoral reform was abandoned by the Liberals.

Nevertheless, here’s an interesting exercise: what would the seat projection look like with current numbers if Canada had moved to a proportional representation (PR) system?

***

Obviously, and I cannot stress this enough, should Canada ever implement some sort of PR, voting intentions would dramatically be altered in this country: grand coalition parties would most likely splinter, new fringe parties would surely emerge, and Canadian politics as we know it would be contested on a radically different landscape.

But still, what if?

Here are the rules of this exercise:

- We divide the country into six regions, which coincide with the usual division of polling in Canada. These regions all retain their current number of districts:

- Atlantic, 32 districts;

- Quebec, 78 districts;

- Ontario, 121 districts;

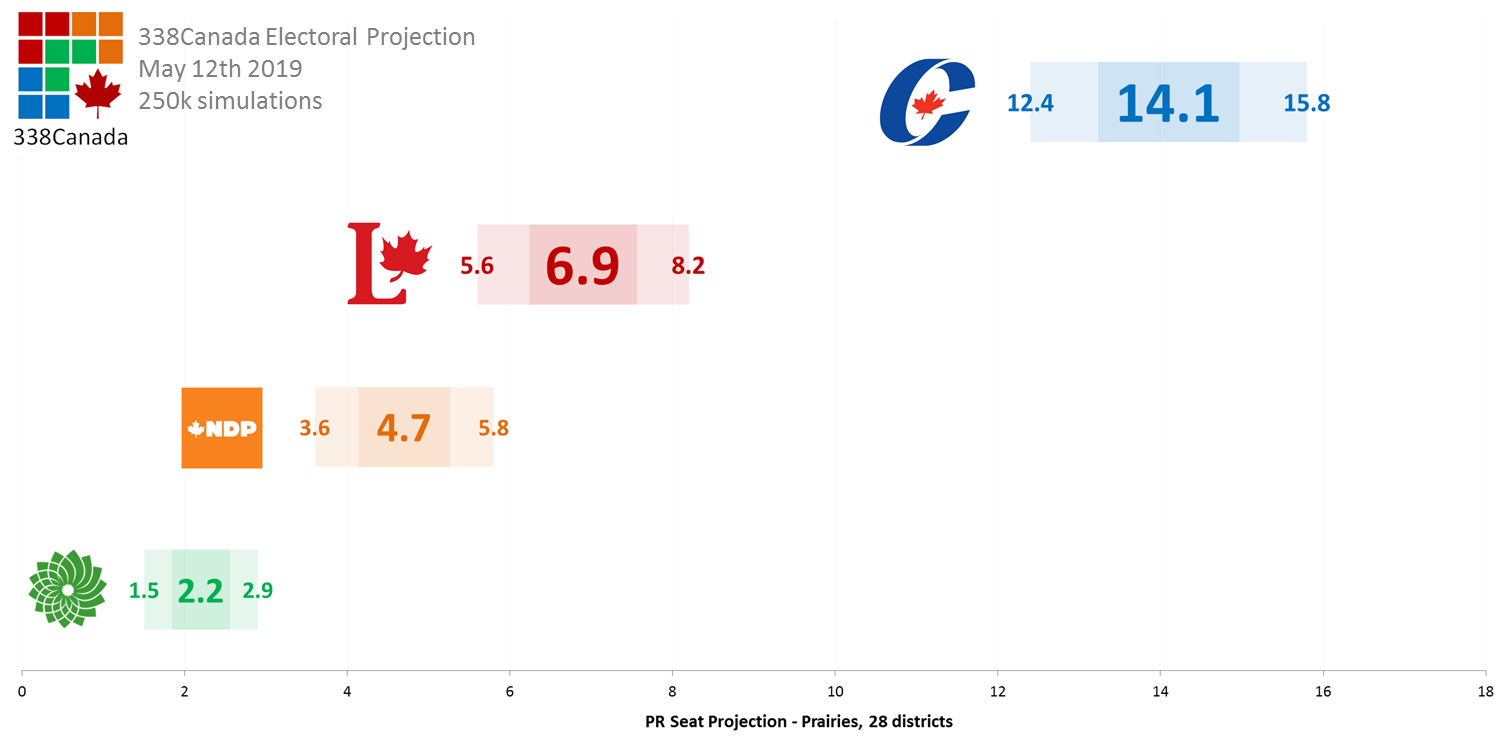

- Prairies, 28 districts;

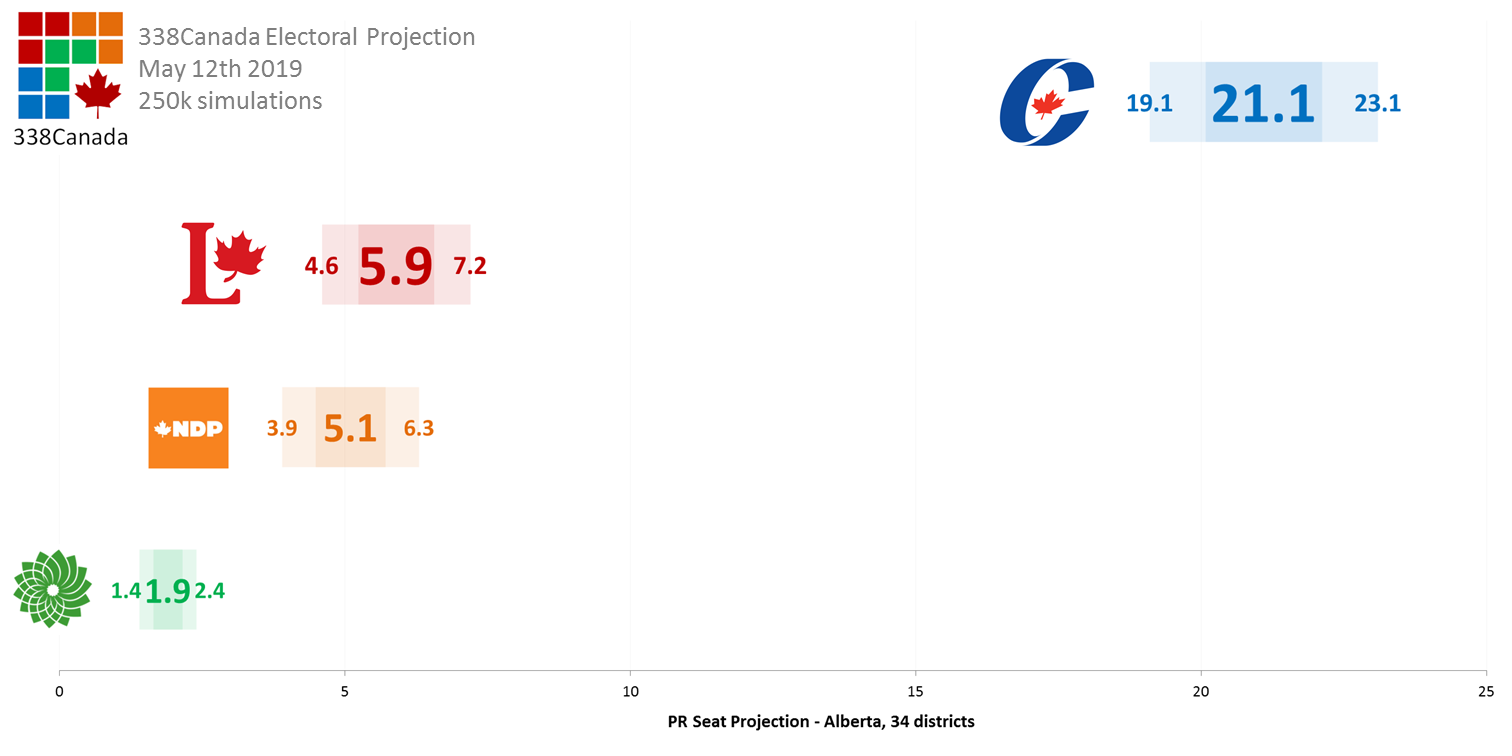

- Alberta, 34 districts;

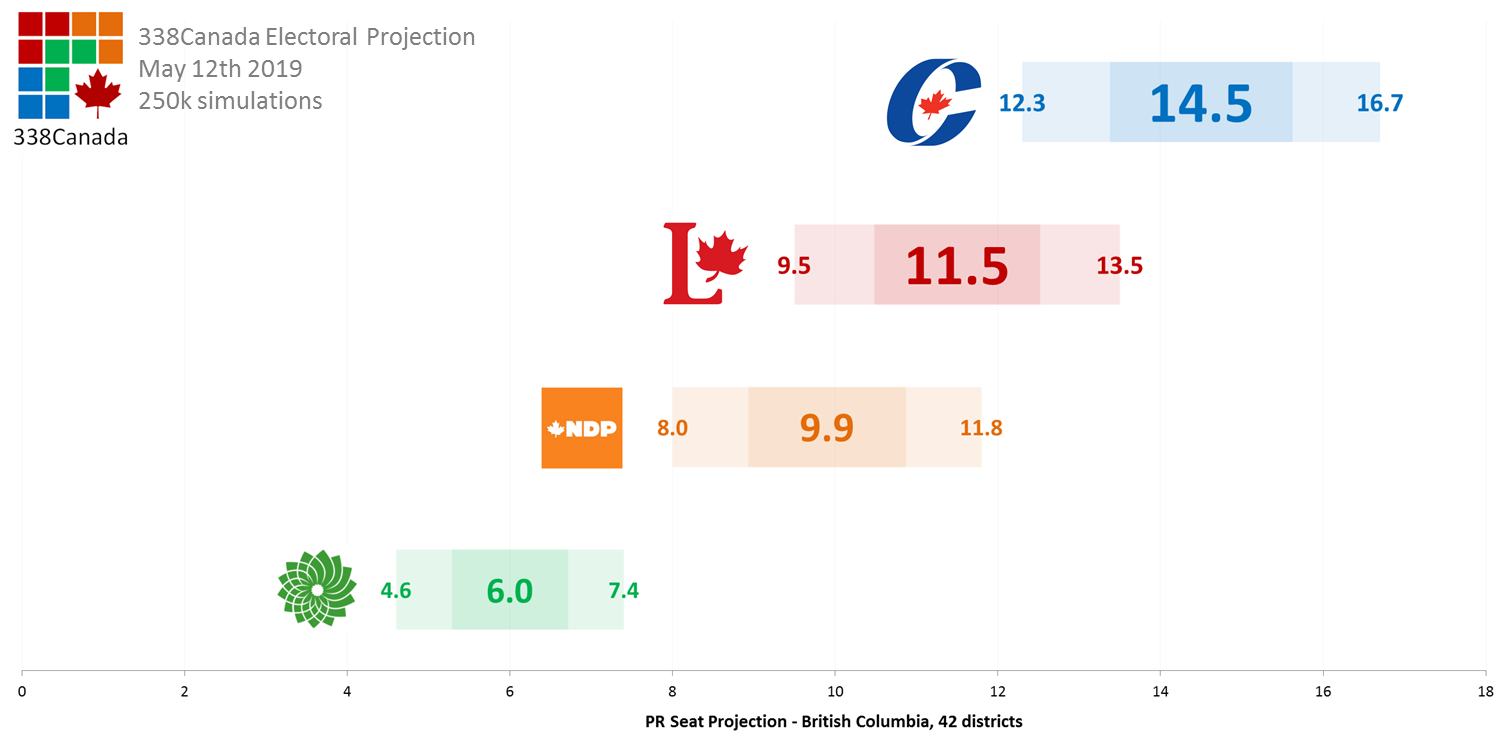

- British Columbia, 42 districts;

- Seats are allocated to parties proportionally to the popular vote share they win per region, rounded to the closest integer.

- A minimum threshold of 5 per cent of the popular vote in a given region is needed for a party to receive a share of seats, meaning if a party doesn’t reach 5 per cent within a region, it receives zero seats and its popular vote share will be ignored in the calculation. Other countries using various forms of PR use such thresholds (Germany’s Bundestag and New Zealand’s House of Representatives also have 5 per cent thresholds).

- The three territories—Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut—remain with FPTP, since we can imagine these communities will surely want to keep their local representative.

For this hypothetical PR projection, we will use the regional popular vote projection per region from the latest 338 Federal Electoral Projection.

Let’s analyze the results.

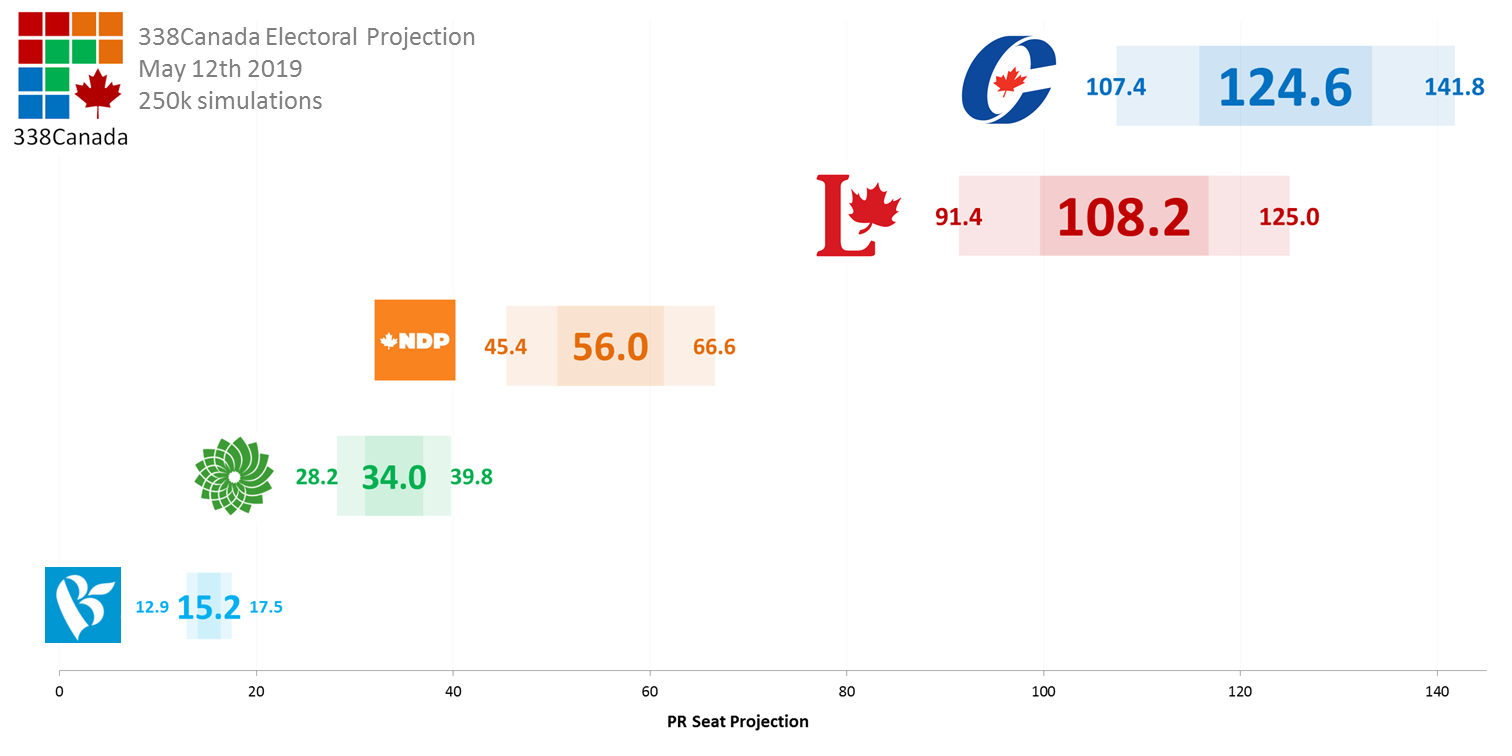

National seat projection under PR

Under the regional proportional representation system described above, the Conservative Party of Canada would be projected at an average of 125 seats—the highest amongst parties, but a total that would be far from the 170 seat threshold for a majority at the House of Commons. The Liberals would win an average of 108 seats.

Here are the PR seat projections with 95-per-cent confidence intervals:

The most striking numbers are certainly those of the NDP and Greens. Under a regional PR system, the NDP would win an average of 56 seats, almost double its current seat projection under FPTP.

Similarly, the Greens’ seat projection would jump from a mere three or four isolated seats on Vancouver Island to an average of 34 seats nationally—an almost 10-fold increase. Moreover, unlike under our current system, the Greens would win seats in every region of the country, as we will see below.

(A quick note on Maxime Bernier’s People’s Party of Canada: since it is not presently polling at or above 5 per cent in any of the aforementioned regions, the PPC would not be allocated any seat.)

Naturally, an important question to ask in regards to the above seat projection is: who would be prime minister? And which party (parties?) would form government? We may assume that current parliamentary rules would still apply, meaning the party (or coalition of parties) that wins confidence of the House would get the first crack at governing. But there aren’t many combinations of parties that reach the 170-seat majority mark with the numbers shown above.

Any kind of Conservative-Liberal coalition would be unthinkable in the short term, and neither would a Conservative-NDP coalition (or would it?). And these, according to the numbers above, are the only two-party combinations that add up to more than 170 seats—which means that, inevitably, the Greens and/or the Bloc would have to be involved.

Let’s take a look at the regional seat projections using this model of PR.

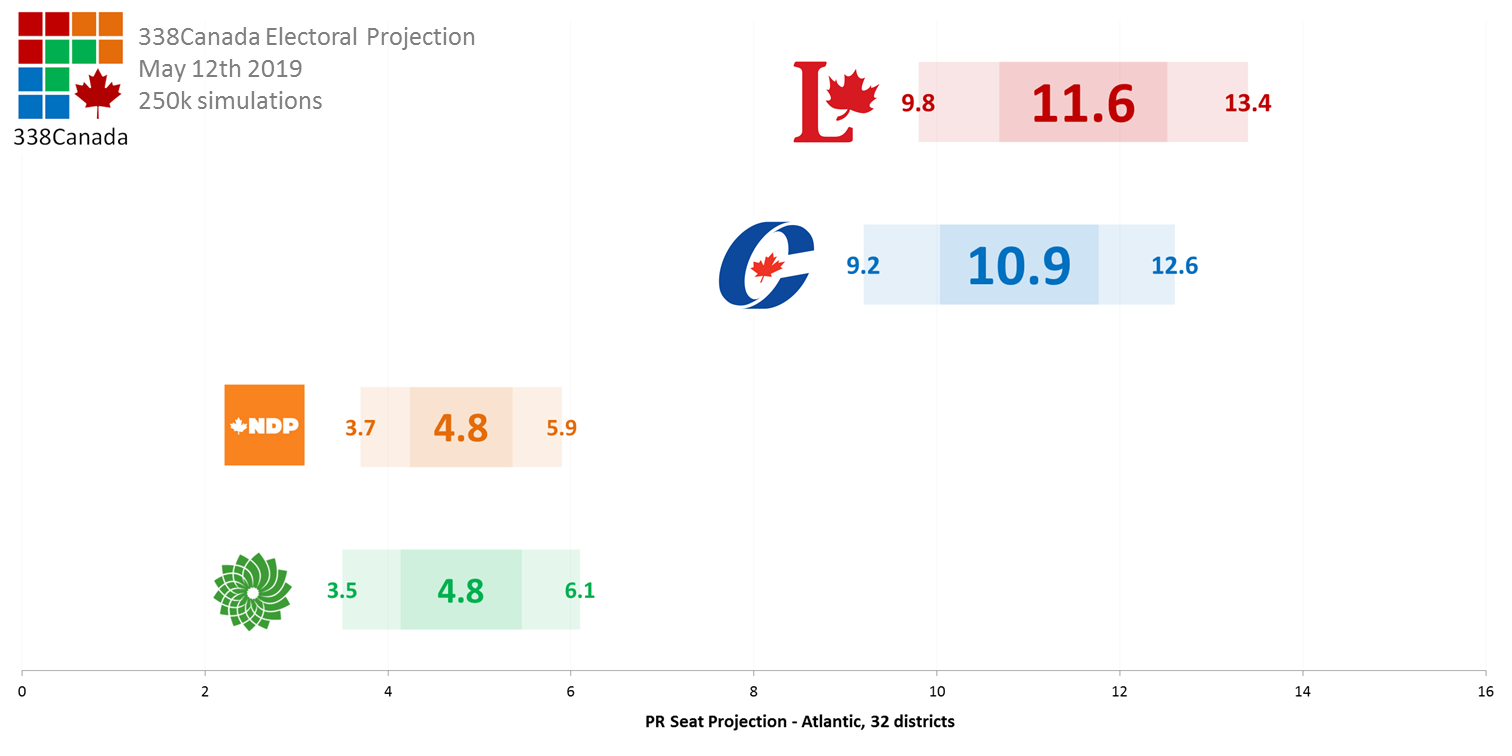

Atlantic Seat Projection

In the Atlantic provinces, polls have the Liberals and Conservatives in a statistical tie. Under a regional PR, their seat totals would be almost identical. Naturally, the NDP and Greens would have much better representation with five seats each on average.

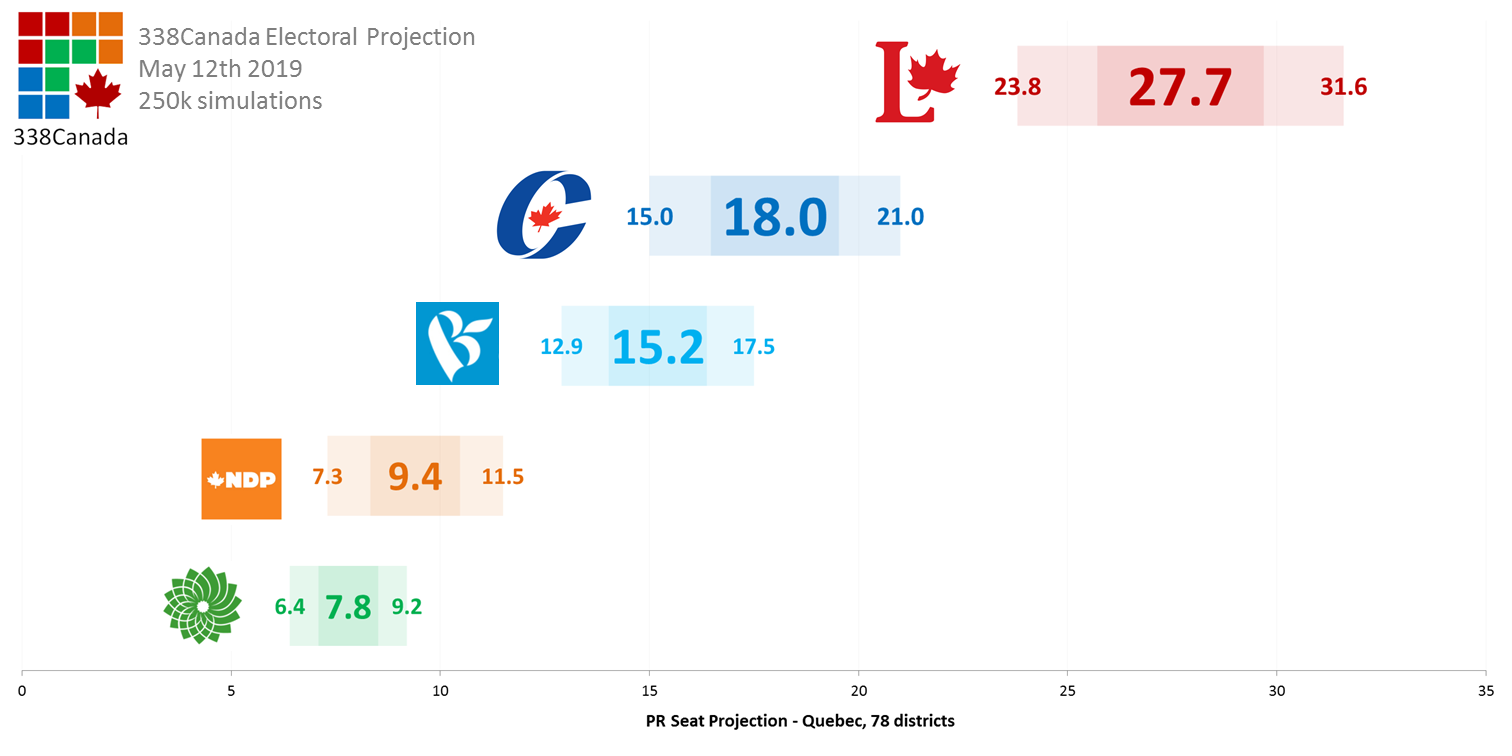

Quebec seat projection

In Quebec, the Liberal seat projection would be dramatically reduced under PR, whereas the Conservatives and the Bloc would be projected at similar levels. Once again, the NDP and Greens would be clear winners with nine and eight seats, respectively.

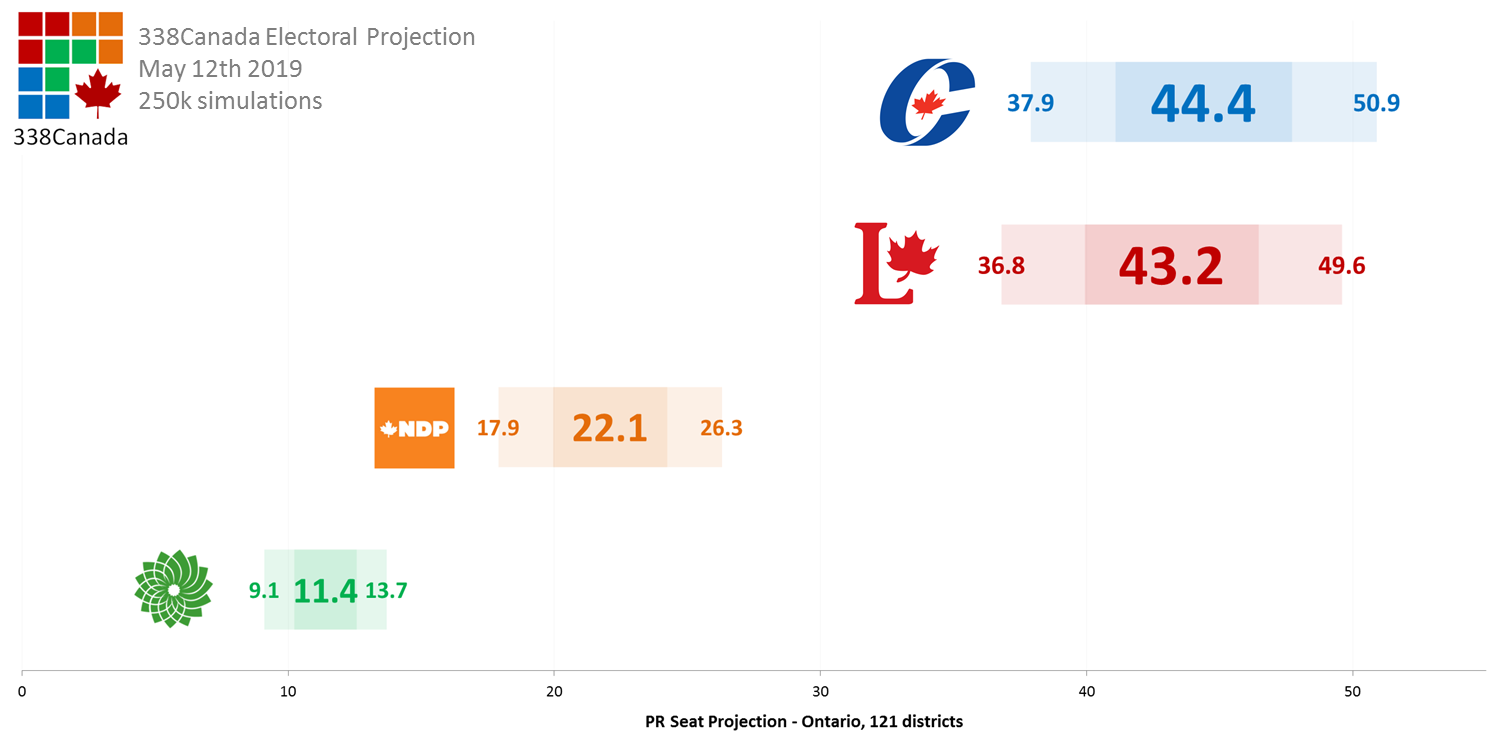

Ontario seat projection

In Ontario, Conservatives and Liberals would win close to 90 of the province’s 121 seats. The NDP and Greens would be projected at 22 and 11 seats, respectively.

Prairies seat projection

In the Prairie region (Manitoba and Saskatchewan), the Conservatives would still dominate the seat projection, but the Liberals, NDP and Greens would still win their share of seats (which obviously is not the case under FPTP).

Alberta seat projection

The Conservatives are currently projected to win 33 of Alberta‘s 34 federal seats, or 97 per cent of the province’s seats. Under PR, the Conservative dominance would be reduced to about two thirds of seats, with the Liberals, NDP and Greens picking up seats that would otherwise be unwinnable under FPTP.

British Columbia seat projection

Finally, British Columbia is probably the region where the PR projection changes the least from FPTP, since all four parties are competitive in parts of the province.

As in the case of our hypothetical NDP-Green merger simulation, this regional PR projection is an exercise of pure politics-fiction. Neither the Liberals nor the Conservatives have shown any interest whatsoever in promoting such reform and, from these numbers above, we can understand why.

After recent referendum losses in B.C. and P.E.I., will the proponents of PR bring electoral reform back to the national discussion this fall? With Conservatives projected on the edge of a majority with a little more than a third of the vote, we should expect centrist and left-of-centre parties to go full steam on this issue—except for the Liberals, of course.