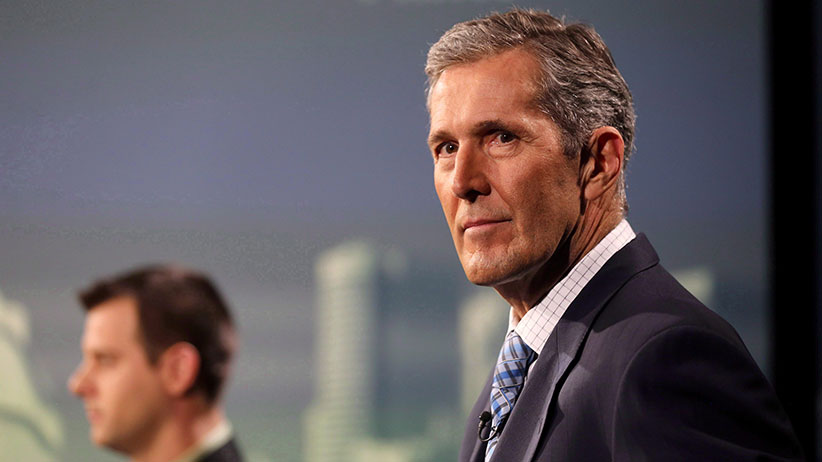

Premier Brian Pallister’s extended escape from Winterpeg

The Manitoba premier is spending weeks away in Costa Rica. His extended breaks raise questions.

Brian Pallister’s home at 761 Wellington Cres., Winnipeg. (Mike Deal/Winnipeg Free Press)

Share

It was so cold throughout southwestern Manitoba earlier this month that the provincial hotspot was none other than Churchill. Daytime temperatures in the northern burg on Hudson’s Bay hovered at -31° C, with the wind chill. In Winnipeg, the wind chill factor pushed temperatures to a point when skin can freeze in five minutes. That curse-worthy cold snap came hard on the heels of a blizzard so bad it left one city senior trapped inside his house for three days, stranded by three-foot drifts blocking the door. In other words: January in Winnipeg, a time when even the hardiest ’Tobans dream of the tropics.

For the Manitoba premier, however, the pura vida is reality.

In December, Brian Pallister announced he would spend six to eight weeks at his vacation property in Costa Rica in the coming year, a move apparently intended to pre-empt controversy surrounding his extended breaks to his estate there. Last April, in the dying days of Manitoba’s spring election, Pallister was caught in a couple of bald-faced lies about his time in the Central American country.

The CBC reported that Pallister had spent one of every five days in Costa Rica since being elected Progressive Conservative leader in 2012, way more than he’d ever let on. He was there, it turned out, for a 14-day stretch during the Manitoba floods of 2014, a time when the province declared a state of emergency, the military had to shore up dikes and the prime minister toured the disaster zone. Throughout, the party had stonewalled reporters’ questions about the Opposition leader’s whereabouts. When the Winnipeg Free Press tried to pin him down, Pallister claimed he’d been at a family wedding outside the province. Similarly, time he claimed he’d spent in North Dakota turned out to have been spent in Tamarindo Beach, where he owns property.

In any other election year, this would have caused serious problems. But voter fatigue with the ruling NDP ran so deep that Manitobans gave Canada’s Tico premier a majority. The dust-up, however, clearly stung, hence the recent Costa Rican glasnost.

There’s no question of Pallister’s work ethic: He built an insurance and investment firm from the ground up over three decades, and once earned a spot on the University of Brandon basketball team as a walk-on after losing 30 lb. running sprints.

Pallister’s office tells Maclean’s that in situations where the premier’s input is needed, he can be patched in from the country, as was the case in December, for a call with Canada’s 12 premiers regarding federal health care funding; and other ministers can stand in to deliver the premier’s messages for him. Further, they say these “working vacations” coincide with sessional breaks, and involve a significant amount of “reading of briefing notes, reports and other documents.”

But it’s not really what he’s doing down there that bothers Manitobans. Though his office says Pallister has no documents delivered to him in Costa Rica, in the wake of the Russian hacking scandal that influenced the recent U.S. election, the move raises questions about the security associated with Costa Rican servers and networks.

Security aside, NDP justice critic Andrew Swan wants to know whether “cabinet is doing anything in the eight weeks he’s away—they can’t meet without him.” To have the premier vacate the office two months of the year creates real problems, Swan adds. A number of capital projects and provincial programs will have been put on hold, awaiting approvals or budgets from the premier’s office. An editorial in the Free Press in December argued “much of his understanding of the needs of Manitoba comes from him physically being here.”

Clearly, Pallister’s time in the tropics makes him an anomaly among premiers. His predecessor, NDP premier Greg Selinger, didn’t spend any time at all outside Canada during his last year in office, when not on official business. Alberta Premier Rachel Notley did not leave Canada last year, unless required for work. B.C. Premier Christy Clark spends a few days outside the country for pleasure every year, though in 2014, she and her son, Hamish, spent two weeks in southern India volunteering in a school-building project. Clark, like other premiers, spends the bulk of her downtime inside the province, often at her family cottage on Galiano Island, just off Vancouver Island. Indeed, when asked of his travel plans this summer, Nova Scotia Premier Stephen McNeil gave Maclean’s the rhetoric typical of the office: “Why would I ever want to leave this place?”

There’s the rub. Canadian premiers act as unofficial ambassadors. They’re every province’s No. 1 booster, and endlessly talk up its economic, trade and tourism opportunities. What does it say about Manitoba—the unbearable cold, mosquitoes, barely existent summers—that its premier chooses to spend as much time as he can away from it?