The people for Donald Trump

Talking to ordinary Americans during this long campaign offered signs of the Trump surge to come

The U.S. Captiol is seen November 8, 2016 in Washington, DC. Voters go to the polls today for the U.S. presidential election. (Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Share

Her name was Lily Markov and she lived in an aging high-rise, hard by the Atlantic Ocean, named for the father of Donald Trump. It was the summer of 2015, long before the first Republican Party primaries, back when Trump, that gilt-plated tycoon and purveyor of reality-show dreams, still was seen by the American political establishment of both major parties as a fake, a poser, a howler, a phony, a joke.

The elevator at Trump Village was on the fritz, Lily Markov complained to a Maclean’s reporter in Coney Island in Brooklyn, and the lights didn’t work and the corridors were dirty. Only one man could repair this, she declared, and this was the building’s eponym, a 70-year-old billionaire tax evader and leering reprobate who would be a joke no longer come Election Day, in the closest presidential election in more than a century.

“I wish I could talk to Donald Trump because in this building we have a lot of problems,” Markov said that summer’s day. “I think that if I called him, he would answer the phone, and he would come to fix what is wrong.”

Fifteen months later, this plea for a self-obsessed, faux-blond hero to descend from his penthouse and ride to the rescue of the common woman and man would resonate across the United States—from the Rust Belt to the Gulf Coast and from burgeoning New England to benighted Detroit—as an irreparably divided American electorate faced a choice between dynasty and delirium.

“Could you imagine Hillary Clinton knowing how to fix an elevator?” Markov was asked that day in Coney Island, and she only laughed, just as the smug revelry of Saturday Night Live would reciprocate by mocking Trump, week after week, as a pouting, preening fool. Today, no one—no matter whose hands the bouncing nuclear football would fall into when all the votes were counted—will laugh at Donald Trump.

The question of whether a saner, less despicable Trump might have won decisively by sticking to economic issues rather than race-baiting, name-calling, and an unsubtle incitement to armed revolt will be left for historians to decide.

A traveller on the campaign trail this year saw this coming from coast to coast—in the women in North Carolina who professed to yearn for a woman in the White House, “but not that woman”; in the men at caucus in Iowa who said “he says what we have all been thinking”; and in the soul-stirred young men and women who flocked to the rallies of Bernie Sanders, puncturing Clinton’s inevitability in a rigged primary that the Vermont senator would have won had the Clinton machine not commandeered a decisive lot of superdelegates before the voting even started.

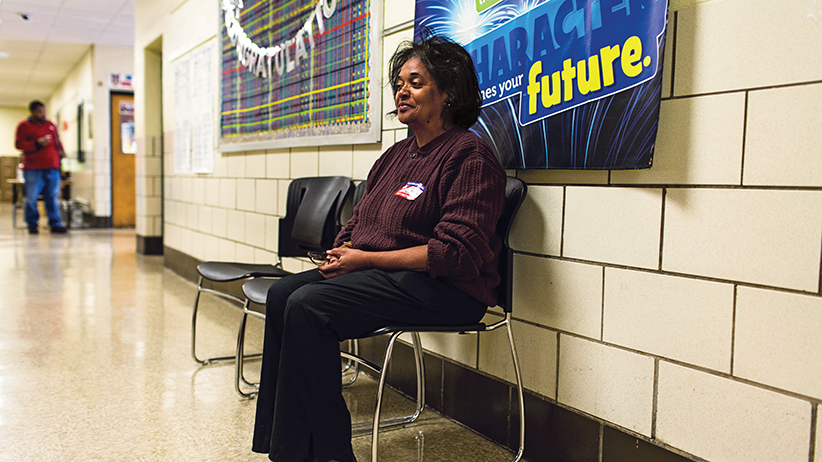

And then—long after the leaked “grab ’em by the p—y” audio; after the ugly mocking of the mother and father of the dead Muslim soldier; after Trump’s thin-skinned and fumbling fulminations in the three one-on-one debates—a woman named Helen Morse reported for duty as a volunteer election judge in a suburb called Capitol Heights in Maryland.

Related: Why I’m voting for Donald Trump

It was a stunningly sunny and temperate morning in Capitol Heights, a nearly all-black community east of the alabaster monuments and million-dollar apartments of the District of Columbia. Morse, a retired legislative assistant at the Environmental Protection Agency, had heard Trump speak many times about the “living hell” that African-Americans were living in; about how “they can’t walk out their doors without getting shot”; about how five decades of Democratic civic governments had done nothing for black people.

And so, in a contest in which Clinton needed and expected every possible African-American vote—and in which President Barack Obama was reduced, at the end, to unbecoming begging for black turnout—Morse cast her sacred, secret vote for Donald Trump.

“When he said that women are stupid, I thought that he was crazy,” Morse said. “When he called Hillary Clinton nasty, I thought that was a very elementary-school word to use. But the more I thought about Hillary Clinton, I thought she might get impeached. You know a snake when you see it in the grass.”

Six years ago, Morse said, “a lady on my block was hanging up curtains and somebody shot her dead.”

Two weeks ago, a few hundred yards from the polling place where she served as a judge, an 18-year-old sprayed gunfire into a crowd of residents rolling dice at 2:45 in the morning and killed a 14-year-old boy.

“I don’t own a gun,” Morse said, “But nobody knows that. I just bluff.

“Law and order,” she went on. “The Republicans can get in and stop the crime.”

This was not unanimous—“What’s hell to Donald Trump? No room service?” snapped Mae Beasley, a Democratic judge at the same Capitol Heights precinct—but it did not have to be unanimous to forestall the elevation of the widely distrusted Clinton from president’s wife to president and delay her gender’s long and hard-won rise from scullery maid to commander-in chief of the most powerful military force that the world has ever known.

Lily Markov, Helen Morse—these were among the millions who would deny to Clinton the automatic victory she believed she was owed after biding her time for eight long years of the Obama presidency while amassing tens of millions of dollars in speaker’s fees.

“We’re gonna win so big you’ll be bored with winning,” Trump promised at every campaign appearance, offering no specifics other than his self-ballyhooed ledger of three decades of artful dealing, much of it, at first, achieved with his father’s money.

“Our convention occurs at a moment of crisis for our nation,” he thundered in Cleveland in July, leaving each elector to select his or her own personal calamity, be it the closing of a steel mill, the rise of ISIS, or wanton murder at a dice game.