Why I ran and how I lost: Kirk LaPointe looks back on his Vancouver race

A first-hand, truly insider account of an unlikely, hard-fought and sometimes ugly race to lead Vancouver

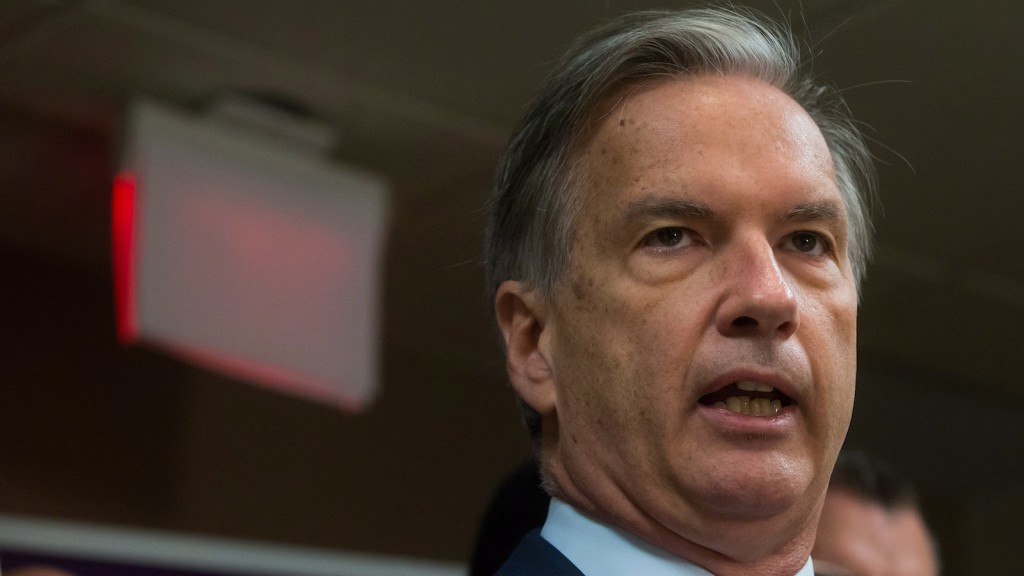

Vancouver mayoral candidate, journalist Kirk LaPointe, of the Non-Partisan Association party, speaks as an exit sign behind him is covered up to hide it during a news conference in Vancouver, B.C., on Thursday November 13, 2014. Voters in Vancouver and other municipalities across British Columbia will go to the polls Saturday for a civic election. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

Share

In mid-March, over lunch, a friend asked my opinion on Vancouver politics and Mayor Gregor Robertson. I wasn’t impressed with him, I said, but I didn’t know who might run against him in November for the Non-Partisan Association (NPA).

“Well, what about you?” he asked.

“Right,” I replied sarcastically/dismissively.

“No,” he said, “I’m here on behalf of the NPA to see if you’d let your name stand.”

I half-expected him to point to the hidden camera and say I’d been punked.

The selection process was unusual and glacial, like a lengthy executive recruitment. Two defeats and divisive internal politics led the NPA to conclude it would best select candidates through a committee and the board. No open nomination meeting, no personal fundraising or spending, and central command for safety’s sake.

Given I was entering public life from a standing start, with a half-dozen months to an election, I was an obvious long shot. No baggage, but no belongings. Even my dog was uncomfortable walking with such an underdog.

Given the state of the NPA, I was sanguine the door would likely only be open now for me. My main objective was to rebuild. Only briefly, much later, was I confident of any chance to win.

I met NPA President Peter Armstrong six times and we developed a rapport to keep me in the hunt for the job. We kept a pact: I wanted certain things for the city, I didn’t have an ideological agenda, I wouldn’t inherit one and I mustn’t be beholden to anyone.

I met the green-light committee for about an hour in late April and discussed why I wanted to run. I had spent a 35-year journalism career seeking answers and now could provide some. I had been a journalist to further the public good and strengthen the community, so this was a big but logical step.

Weeks went by before an audition with the board was arranged. Two others were shortlisted. My mistake was to think I could make a detailed pitch out of memory with no notes. My presentation was fuzzy. I would gain a patter for speeches in the weeks ahead, but, that day, I left wondering if I’d just lost the opportunity.

A week or so later, though, I was in a boardroom with the confirmation of my candidacy for mayor.

The naive expectation is that, once the board approves you, you walk into an adjoining room to see a large organization feverishly at work, then into another room to see a batch of kids sweatily working the phones and painting signs, then into a third room of cigar smoke and city fathers calmly raising money to support your campaign.

There is no other room. When the NPA president points at me across the table and says, “You are now the NPA,” he means it.

The next few weeks were like starting a business, even like deciding which business to start. I had to find a campaign manager, agree to his team, meet each of our 19 candidates to make sure we could work together (we could), and start fashioning the policy framework.

The NPA has elected 11 mayors in eight decades, but it is not a political party, per se. It is more like an alumni reunion society, selecting a slate near election time and dispersing after the vote. We had three full-time employees. Our two-term opponents had a full office and advisers on other payrolls. We had a five-figure bank account. They had a seven-figure one. We had less than five months. They had been working at it six years.

If we had an advantage, it was in the way city hall operated: secretive (opaque financial statements and an aversion to media and freedom of information), alienating (more than a dozen neighbourhood groups and several community centres in court), and distracted (focused on issues outside of city jurisdiction).

A poll suggested one main reason Robertson was liked was that he wasn’t Toronto’s former mayor, Rob Ford. While he was popular (even I liked him at times), his administration wasn’t. Under him, the city grew more divided between motorists and cyclists, resource sector and green sector, owners and renters, private and public, and neighbourhood groups and those who develop the city. The success of Robertson’s Vision Vancouver party had much to do with mobilizing the latter of each and suppressing the former.

I thought the best route was to attach him to the mess, to bridge the divided camps. Vancouver cannot be governed from anywhere but the middle, and that requires a brokered smorgasbord of policies and participants.

Related reading: How the great Rob Ford divide could be coming to a city near you

It is never clear just how much Robertson is the architect and how much he is the front man for the Vision Vancouver brand. He surrounds himself with testosterone in the party backroom and at city hall, and he doesn’t string together particularly lyrical responses to media or council questions, so he is often described as an empty suit. He runs what I called in the campaign a mullet government: pretty in front, lots of weird stuff happening in the back.

We thought I could lean in on this with a strategy to open city hall, make it listen, preserve its social programs, and deal with the overall dissatisfaction with the incumbents. We thought that would build an attractive brand that authentically represented and reflected. What I would discover was that this would go only so far, and that, without a real ballot-box issue, we might not go far enough.

I would learn two things mattered most of all: identifying the supporters and getting them out on election day. And I would experience how dirty the fight would get almost immediately.

The mayor had separated from his wife earlier in the year. One of our board members who knew their family had sent an email about the strife to some acquaintances.

In an odd gamble, the mayor’s party released the email publicly and accused the NPA of smearing Robertson, even though the email had been a private and not a party correspondence. The result was unnecessary attention about Robertson, much of it innuendo.

Even though I wasn’t yet the candidate officially, I posted on Facebook that private matters did not belong in the public sphere. Vision would maintain NPA smeared the mayor, but, by releasing the email, his own party was availing the public of information it need not have known.

I was astonished his party was willing to deepen Robertson’s family’s own personal discomfort if it meant deepening sympathy for the brand and antipathy for the enemy. With friends like that, who needed enemies?

When I announced my candidacy on July 15, I was basically unknown. I had helped to run the Vancouver Sun newsroom and been the CBC ombudsman since moving from the east, but my local profile was negligible. A large part of our early campaign involved getting people to learn how to say LaPointe, perhaps even to spell it.

By my count, I had more than 200 meet-and-greet events, from breakfasts and lunches in offices to days and evenings in homes. When 75 show up, you are elated; when six do, you are enervated. Supporters were magnificent in their effort. Social media is helpful, but word of mouth matters more in these elections.

My platform was workshopped with several people, but, for better and worse, it was largely my own. Unlike my opponent, we didn’t poll before my announcement. My pitch reflected some of my journalistic calls for a transparent government, an ombudsperson, a lobbyist registry, and meaningful campaign-finance reform.

Some was informed by my childhood in poor circumstances: a program to feed hungry children, a mentorship program for tweens and teens. Some was just to make the city more affordable and amenable: citywide WiFi, free Sunday and holiday parking, more outdoor pools. Some was aimed at demonstrating new responsibility: an encouragement of jobs in the resource sector, a new conversation on homelessness and on development.

One beguiling early problem was that Vision and Robertson were touting issues about which they were doing, or could do, nothing, such as stopping a Kinder Morgan pipeline that wasn’t running through Vancouver and would be decided by the National Energy Board. Or promoting a subway that needed the support of senior levels of government to have any chance.

The pretension still caught a nice buzz. The more we pointed this out, the more we were branded as downers, and polls were suggesting people were accepting Robertson’s rhetoric more than the reality.

It was often unsettling to be on the other side of the microphone and the questions, and I spent too much time talking like a journalist and too little like an advertiser. Campaigns call for short sentences, not half-page explanations, and for repetition, not different ways to say the same old thing.

There weren’t enough mainstream media to sustain coverage seven days a week and all summer and fall, and I think that some animus from former employees crept into the coverage without ample declaration of personal conflict. I still cannot understand how a policy platform with more than 75 proposals could be called thin.

Overall, though, I was treated fairly. It was true that our platform lacked the secret sauce for solving affordability issues for housing in the city. So did theirs, but we were expected to offer new answers and, when we didn’t, we alone suffered.

The weirdest part is when signs surface in the last month, where your face is plastered on billboards, pamphlets, lawns and bus shelters. I remember driving beside a passing bus with my face on its side. That photo looked like from a different era.

The worst part (apart from a shock-jock question about self-love) is the emotional toll on our families as we become objectified. It is not their journey, yet they cannot help but be drawn in.

The physical toll is predictably enormous: 14- to 16-hour days in the last month or so, erratic meals, and the necessity to develop new muscle groups and layers of skin.

Our candidates worked like mad, knocking on doors, shaking hands on the streets, sitting for endless all-candidates meetings. Many went from total strangers to my best friends forever. We recruited an extraordinary group of newbies and a great team of veterans to push ahead.

We had signed a code of conduct not to launch personal attacks, but our opponents would not follow suit. As weeks wore on, the mayor thought policy and performance attacks were personal. He definitely didn’t endure what I did.

The first true smear came my way during Pride week. A Broadbent Institute piece orchestrated with Vision’s support discussed a 1999 decision I’d made not to carry a picture on the front page in the Hamilton Spectator of two men kissing. Within minutes, the piece spread across social media from Vision’s team as evidence of my intolerance. Forget that the photo was a publicity stunt, or that it was Hamilton, or that it was 1999, or that my career demonstrates the opposite: I was now a homophobe.

Over the campaign, I was targeted with fabrications from whole cloth: I was against spending on the needy, in favour of closing library branches, against a subway line, in favour of cutting police services, in favour of Chevron messages in the classroom, against the environment, in favour of capturing and torturing whales and dolphins, in favour of more oil tankers in the harbour, being a Stephen Harper or Christy Clark operative, being an extension of the Fraser Institute and the Koch brothers in the U.S.

They had dozens of Twitter trolls, they followed me with a camera and created ads of personal ridicule, and they raised fear at every turn. I wouldn’t have liked the person they concocted.

I was disappointed with the debate schedule and format. Formally, there were six, all in the last month, but the amount of one-to-one time was minimal. In our first debate of two hours, Robertson and I had a total of two minutes of direct encounter. Three sessions were essentially questions directed to us with no opportunity to exchange.

My only real gain was when I challenged Robertson about a pledge on his behalf by one of his councillors at a union meeting not to further contract services. The union gave his campaign $102,000 that night. It was a bad deal for the city and smacked of something way worse. When I asked if he stood by his councillor, Robertson replied, “He’s not my councillor.” Guffaws ensued.

Next morning, with his man under the bus, Robertson had to backtrack. But it enhanced a perception of his inability to think on his feet. Rather than battle in public, in the final 10 days, Robertson and the councillor launched a lawsuit to silence the campaign and suffocate the issue.

When we crept to within the margin of error in polls (our overnight polls had me up a couple of times), they would find another gear in the last few days and we would not.

Their post-mortem spin was that Robertson’s apology for not listening to the community (they polled to make sure it was a decent idea) and his sudden glut of positive ads were the lifesavers. But that is a delusion. The last five days were utterly negative on the ground and via phones and emails. My dog hid, probably because she heard I kicked puppies.

Our result was redeeming overall: 11 elected on council, park board and school board, up from five. I received more than 73,000 votes as mayor, 40 per cent, the most in NPA history. Robertson got more than 83,000. A third candidate, Meena Wong, garnered 16,000, and I suspect she drew more from him than me.

The privilege of running was well worth it. I met thousands of wonderful people. It is a great city, badly run, and the city generally gave a newcomer to politics a chance to earn their votes. It is possible we didn’t so much lose as we ran out of time, but it is more likely that we didn’t have the right combination of ideas and machinery.

This time.