Coronavirus has highlighted Canada’s biggest urban design challenge—elevators

In cities like Toronto, Vancouver and Calgary, where condo dwellers and office-goers rely on elevators as the first and last leg of their commutes, a ride on the lift has become a risk rather than an inconvenience

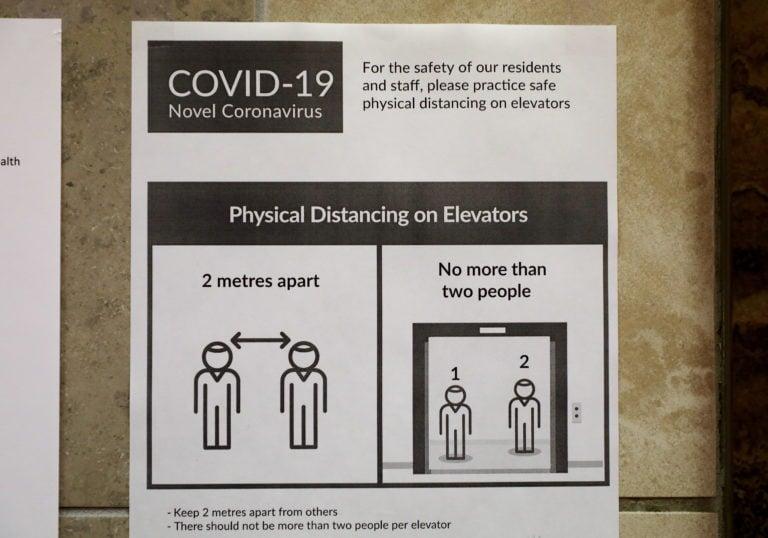

A sign urging physical distancing when using elevators is seen in a high-rise building in downtown Toronto on May 8, 2020. (Colin Perkel/CP)

Share

In a vertical city that boasts about how it leads the continent in active construction sites, the hundreds of thousands of Torontonians living in high-rises have been grappling with the uncomfortable reality that elevators are among the least desirable forms of transportation in a pandemic.

“That’s the most risky thing I have to do,” says Rob McLarty, a software developer who lives on the 33rd floor of a downtown condo tower, says of taking the elevator. So much so that he rarely leaves his apartment. “I’m very anxious as things start to re-open,” he says. “More people will be on the streets, in the grocery stores, and in my building…Knock on wood, I’ve been lucky I haven’t gotten sick yet.”

At the request of public health authorities, landlords have imposed limits on the number of people who can ride at one time; in older high-rises with cramped lifts, that number may be no more than two, which means line-ups in lobbies and testy encounters after an extra person boards instead of waiting for the next one.

MORE: What will shopping in Canada look like in the aftermath of coronavirus?

The confined dimensions and limited air circulation in elevators pose the same kinds of potential health risks as do other tight indoor spaces. Richard Corsi, dean of engineering at Portland State University, worked up, and then tweeted, a theoretical estimate on how aerosol-born coronavirus might linger in an elevator after a passenger speaks or coughs. Corsi estimated that elevator air could remain infectious from viruses emitted by an asymptomatic individual riding up 10 floors, even after they’ve exited. Other experts disagree, and Corsi admits that his calculations are uncertain because much about the virus’s behaviour isn’t clear.

While the epidemiological evidence to date doesn’t specifically finger elevators as a contagion vector except in hospitals, the emerging picture of the geography of the pandemic shows that COVID-19 is far more prevalent in low-income, racialized suburban communities where residents tend to live in high-rise apartment complexes built in the 1960s and ‘70s.

This isn’t just a Toronto story. People who live in high-rise districts in Vancouver, Calgary, and Montreal are all contending with the same issues, as are people in other vertical neighbourhoods in other cities.

MORE: Quarantine nation: Inside the lockdown that will change Canada forever

As the New York Times recently reported about life in a pair of low-income Bronx high rises dubbed the “death towers” for the high rate of infection among tenants, “Residents often must wait up to an hour to squeeze into small, poorly ventilated cars that break down frequently, with people crowding the hallways like commuters trying to push into the subway at rush hour.” In Vancouver, meanwhile, a media storm erupted when reports containing CCTV video showcased a man spitting on the buttons of an elevator panel after the pandemic lockdown began.

Yet as the economy lurches haltingly into gear, the flip side of the elevator story is also coming into sharper focus as high-rise office towers, some of which are used by some 5,000 people each day, slowly come back into daily use. Property management firms are now scrambling to set up procedures to get office workers in and out as expeditiously as possible.

Indeed, for the many city-dwellers for whom an elevator ride—the dullest of all urban journeys—is both the first and last leg of a daily commute, pandemic life has injected an added layer of anxiousness and delay that simply doesn’t affect people who live in houses, work from home or have jobs in low-rise buildings.

“Invented for convenience and utterly mundane mere months ago, elevators now stand out as anxiety boxes that encapsulate all manner of social issues in cities,” commented journalist Laura Bliss in a recent essay in CityLab.

“We’ve designed buildings based on an optimized number of people going up and down and now the math is difficult,” says Ryerson University urban planning professor Pamela Robinson. She describes elevators as one of the most inflexible forms of urban transportation: once installed, there’s not much room for improved performance. “I wonder if we can design our way out of this?” She asks.

* * *

Along with transformative technologies like the subway and steel-frame construction, the elevator—invented by Elisha Graves Otis in 1852 and first installed for commercial use in New York City five years later—enabled the emergence of the compact, modern city. They produced controversy and angst almost from the get-go, as New York newspapers ran stories about elevator etiquette and speed.

But as Randy Lippert, a University of Windsor sociologist and author of Condo Conquest points out, “the role of the elevator has always been taken for granted.” In his book, Lippert notes that urban transportation networks should account for what he calls “the Z axis” (i.e., vertical mobility). But at Ryerson, Robinson says, few municipal planning departments think about elevator congestion.

Case in point: elevator break-downs have become endemic in Toronto, which has a severe shortage of repair technicians, so service calls can be delayed for months. In 2018, Ontario’s auditor general warned about wide-spread elevator safety and maintenance issues, with as many as 80 per cent failing routine inspections.

In ordinary times, an out-of-service elevator is an inconvenience. But with passenger limits in place for the pandemic, the loss of an elevator in some high-rise buildings can reduce the capacity by 25 to 50 per cent.

Some buildings were simply designed with inadequate capacity. Miguel Avila, an activist and resident of Toronto’s Regent Park, an affordable housing complex that’s seen significant intensification in recent years, points to a new 21-storey seniors’ building in the area with only two lifts. “It’s an architectural design flaw,” he says. Sometimes, Avila adds, three tenants crowd in “because they have no choice.”

In Rob McLarty’s 33-storey condo tower, some residents wait for an elevator with only one occupant before boarding, but others don’t care. “Those are the ones I worry about,” he says. Lobbies, moreover, have become choke points because that’s where the line-ups occur, and typically those spaces aren’t meant to accommodate large numbers of people who are expected to keep two metres apart. These ground floor areas, he adds, are a kind of regulatory grey zone—simultaneously private and public, but beyond the jurisdiction of public health officials.

The vigilance of the building management also seems to vary greatly. In McLarty’s building, there’s little evidence of monitoring beyond wipe smudges on the elevator panel. By contrast, Avila, who lives on the 10th floor of one of the Regent Park Toronto Community Housing towers, says the superintendent has been proactive about monitoring the number of passengers, providing hand sanitizer and cleaning panels.

In Vancouver, health authorities have been especially assertive about new elevator protocols, says planning consultant Brent Toderian. “Face the walls, use a tissue to touch buttons, no more than two people or a single family per car, sanitizer at elevator entrances, and it suddenly became okay to press the ‘close door’ button!”

Office towers are another story again. In recent weeks, commercial landlords have been bracing for the return of office workers by installing floor markings, signage and partitions, urging them to do staggered work hours and creating new protocols for lunch breaks. But with maximum capacity on high-speed office building elevators cut from 10 to 12 passengers to three or four, the queues could get very long very quickly.

Cary Solomon, CEO of Next Properties, which owns and develops mid-rise offices in Toronto, says his firm is looking at various measures, such as an app, currently under development, that would allow office workers to enter their floor destination from their phones instead of pressing buttons. Other firms are investigating the use of ultra-violet light that could sterilize surfaces within the cab. “There’s a whole host of things landlords are thinking about because people are going back to work,” he says.

Engineering consultant Jon Soberman, who advises developers on their elevator infrastructure, adds that property managers could fairly easily improve air circulation in elevators by turning on the ventilation fans affixed to the roofs of cabs in case of emergencies but tend to be switched off. But beyond such tweaks, he adds, “I don’t think there are a lot of options, to be frank.”

The long-term question is whether these elevator-related pandemic stresses will slow high-rise condo sales or help push the tenants of office buildings to choose to relocate to low-rise suburban locales that are mostly accessible by car. Solomon doesn’t foresee an exodus, and notes that people miss coming to work, getting dressed for the office and being with their colleagues. “The move away from the office is not going to happen,” he predicts. “A lot of people I’ve spoken to can’t stand working from home.”

Ryerson University urban planning expert Pamela Robinson, however, says developers and architects need to begin thinking about building elevator capacity redundancy into their plans. “Maybe we need a new building typology,” she states. Developers, however, say it’s unlikely that the current situation will make much of an impact on the design of high-rises or the provision of elevator capacity.

Stephen Diamond, CEO of Diamondcorp, a Toronto high-rise developer, recalls that many people talked about fleeing high rises after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001, but the fear dissipated within a year or so.

For his part, Diamond says the trade-off is less saleable or leasable floor space. “It’s all a balancing act,” he observes, adding, “If the consumer begins to demand less people per elevator, then the industry will respond to the consumer.” But if condo buyers only want to buy in buildings with larger elevators or more stacks, they’ll have to settle for either smaller units or more expensive ones. For those living in old apartment blocks catering to newcomers or those who live on low incomes, the choice is moot.

After three months of isolating, stressing and keeping his vertical journeys to the absolute minimum, McLarty has had more than enough of high-rise condo living in a pandemic. “I’m thinking of moving later this year,” he says.