Is Canada discriminating against foreign-trained doctors?

A new survey suggests they are disproportionately more likely to be charged with professional misconduct

Share

When Dr. Minoli Amit moved with her ophthalmologist husband from their Dalhousie medical school environs in Halifax to rural Nova Scotia to set up practice, they had two very different experiences getting started. “He had referrals right away and I was very slow gathering referrals,” recalls Dr. Amit, a pediatrician at St. Martha’s Regional Hospital in Antigonish.

This was because of a case of mistaken identity, she says: Colleagues and patients continually confused Sri Lankan-born Dr. Amit for an international medical graduate—an assumption people did not make about her Nova Scotian husband. She remembers one telling anecdote: About five years after into her career in Antigonish, a family doctor stopped her in the corridor of her hospital and exclaimed, with a sigh of relief, “I didn’t know you went to Dalhousie! That makes the biggest difference.”

Now, Dr. Amit sees herself as a sort of interpreter. Continually being mistaken for an outsider to the health system gave this Canadian physician unique insights into the challenges foreign-trained doctors face. “Because I happen to straddle both worlds, I make it my business to try to get to know people who have come from other places,” she says. And, she adds, “I don’t think we do a good enough job of orienting physicians. We send them off to these small places, with few other professionals… Frequently, the only person they have to communicate with for support may be the medical director of the district, who may be physically removed. You’re very fortunate if you have a partner who pays attention to you, otherwise you just struggle on your own.”

And yet Canada desperately relies on foreigners to come in and beef up the scant supply of locally-trained physicians. We have never produced enough doctors to meet the health needs of the Canadian population. In fact, Immigration Minister Jason Kenney announced this week that Ottawa is pondering fast-tracking international medical graduates into the system to “respond to current and future shortages and across the spectrum of the labour market.” But as much as we appear to like the idea of importing doctors, once the newcomers reach our shores we don’t seem to have so much as a welcome mat ready for them.

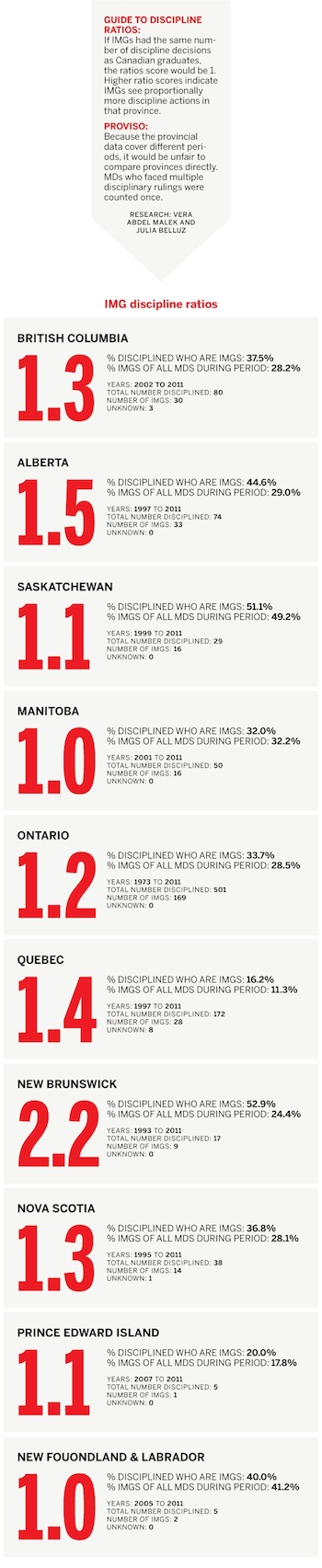

As the data to the right shows (click on the chart to view it full-size), a recent investigation of disciplinary action against doctors conducted by the The Medical Post, Canada’s physician newspaper, suggests Dr. Amit’s impressions may be correct. The survey, the first one of its kind to be conducted in Canada, showed that in nearly every province, doctors who received their MDs outside this country and the U.S.—including Canadians who studied abroad—appear to have been disciplined disproportionately more often than their North America-trained colleagues.

As the data to the right shows (click on the chart to view it full-size), a recent investigation of disciplinary action against doctors conducted by the The Medical Post, Canada’s physician newspaper, suggests Dr. Amit’s impressions may be correct. The survey, the first one of its kind to be conducted in Canada, showed that in nearly every province, doctors who received their MDs outside this country and the U.S.—including Canadians who studied abroad—appear to have been disciplined disproportionately more often than their North America-trained colleagues.

Canada wouldn’t be the first jurisdiction where this is the case. For example, in the United Kingdom, a 2003 study published in the British Medical Journal concluded doctors trained overseas were nearly twice as likely to be charged with professional misconduct.

Some physicians believe the problem here lies in a patchwork approach to orientation for doctors who aren’t used to the Canadian system and may therefore commit mistakes that have more to do with linguistic and cultural challenges than their professional preparedness. As Dr. John Haggie, president of the Canadian Medical Association and a foreign-trained doctor himself, put it: “There really was very little in the way of orientation into the system until quite recently. Certainly it must be a real challenge to have English as a second language and come from a culture so completely different.”

When the Medical Post approached the provincial medical colleges, which police the profession and are responsible for disciplinary decisions, about the survey results, they overwhelmingly acknowledged that there is a need to standardize support and orientation for these international medical grads.

For Dr. Haggie, a general and vascular surgeon who immigrated to Canada from Manchester, U.K., in 1993, it was a case of “two continents divided by the same language,” as he puts it. When he arrived in St. Anthony, N.L., the local culture seemed familiar enough, but the use of language sometimes tripped him up, and he had to wrap his head around completely different drug names.

According to Dr. Ian Bowmer, executive director of Canada’s Medical Council, communication issues—whether they arise from language missteps or poor interpersonal skills—are a key predictor of trouble for physicians. Studies of complaints about doctors in Ontario and Quebec have shown that those who perform poorly on the communications component of the OSCE—a compulsory standardized test for doctors that measures clinical skill performance and competence—are more likely to have disciplinary actions against them. Though the studies did not look at where physicians obtained their MDs, Dr. Bowmer said, “It would seem to me that if someone is functioning in English as a second language or French as a second language, communication might be part of the problem.”

Of course, foreign-trained doctors in Canada are not a homogenous group. They include folks who got their MDs overseas and spent years honing their specialities in culturally similar or English-speaking countries before arriving in Canada, and Canadians who studied abroad. But whether you’re Canadian or not, getting to practice in Canada is no easy feat. Our standards are among the highest in the world, and every province makes sure foreign-trained doctors live up to them by testing their knowledge and mandating additional training when necessary.

Still, sometimes how quickly they head into practice depends more on patient need than preparedness to work in Canada. Dr. Haggie summed it up quite well: “There are some areas where you have nobody (practising)… and the urge to put a physician on the ground can be very overwhelming.”

Some worry this kind of physician churn raises quality issues. John Abbott, CEO of the Health Council of Canada, said, “We’ve always relied on (international medical graduates) and to me that speaks to a weakness in the system.” He continued: “If we’re going to rely on (these doctors), they need to be acclimatized, culturalized and trained to the Canadian standard before they are allowed to practise.”

A 2009 Canadian Institute for Health Information survey found that, at the high end of the spectrum, international graduates made up 46 per cent of the total physician workforce in Saskatchewan and, on the low end, only 11 per cent in Quebec. The Canadian average was 24 per cent—so, roughly one-quarter of the doctors in this country were educated elsewhere.

Admittedly, the Medical Post investigation warrants further study: the data were not robust enough to answer questions such as whether the foreign-trained folks who were disciplined were born in Canada or abroad, what the gender breakdown looked like, or how many years of practice they had before being disciplined. It’s possible that the characteristics of international medical graduates as a group correlate to the kinds of doctors who—in general— are disciplined more frequently (ie. male general practitioners at a certain stage in their career).

Getting stronger data may not be easy, though. The provincial colleges in Canada tend to operate like black boxes and there’s little standardization across the country when it comes to the ease of access to information on a physician’s history and disciplinary action taken against him or her. Simply gathering the information for this Medical Post investigation was a trying exercise. But, since our dependency on foreign medical graduates isn’t going to subside anytime soon, shouldn’t we take the time to understand the needs of this group, how these doctors perform in the system, and whether they are being treated equitably?

As Dr. Amit says: “There’s an elitism and snobbery that goes on with regard to training here versus training somewhere else.” And she’s not the first one to note that.

Perhaps the real reason we don’t have better data on this is that we don’t want to know. As Dr. Trevor Theman, the registrar of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta, told the Medical Post, his college has not yet explored trends on disciplinary action—and probably never will: “In part because it raises the question of—if there is a problem, what would you do about it?”

Julia Belluz is the associate editor at The Medical Post. She writes the blog Science-ish. Message her at [email protected] or on Twitter @juliaoftoronto