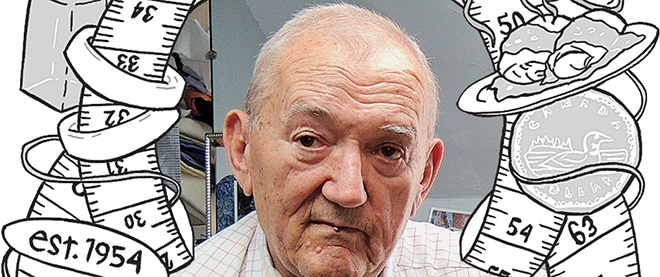

Ljubisav ‘Gilbert’ Lazich

At six foot one, he was big; his customers were bigger. In his commitment to the perfect fit, retirement was never an option.

Ted Lazich; Photo Illustration by Julia Minameta

Share

Ljubisav “Gilbert” Lazich was born on April 9, 1928, in the village of Slobostina in the former Yugoslavia; he was only six months old when his father Teso sailed to Canada looking for work and landed in the Great Depression. Gilbert’s three older brothers died of typhoid, and he was raised by his epileptic mother Stana. During the Second World War, Germans razed the family home, but Gilbert stayed in the village until his mother died when he was 17. Gilbert, tall, handsome and poor, set off to Belgrade to learn a trade. He became a tailor even though his fellow apprentices teased him for his big hands.

Two years later, Gilbert returned to his village in an impeccable grey pinstripe suit for a local dance, where he met a 15-year-old beauty in a blue dress. Her name was Stella, and she had survived Hitler’s army by hiding for weeks in a hole covered with leaves and dirt. Gilbert asked her to dance the polka, while a guitar, bass and accordion carried the beat. After Gilbert returned to Belgrade, he wrote her a letter, “a little bit of a love story, nothing much I believed,” Stella says. She didn’t bother replying. But the young suitor returned in a few months bearing a bottle of plum brandy and a marriage proposal. He told her, “We’re orphans, we’re going to make it in this world. We have to make it.” He wanted his young wife to own a suit, so he chopped up his own and remade it to fit her.

Gilbert’s father, still in Canada, wrote his son and said he could hire someone to smuggle the couple out of the postwar gloom of Yugoslavia. So they snuck across the closed border, through bushes, down a steep hill, over a running creek. From Austria they flew to Toronto—they called it “America”—and all they knew was that everyone there was rich.

They settled in Hamilton, where patient neighbours would repeat their questions three or four times to Slavic ears still labouring to decipher English. Gilbert decided to start up a clothing store devoted to the oversized, and in 1954 Gilbert’s Big and Tall opened. Stella and Gilbert and their three children—Tom, Katy and Ted—lived above the store. Gilbert was big at six foot one; his clients were bigger. “Anybody can sell clothes,” he’d say. “We sell fitting clothes.” Tree-trunk necks, rotund bellies and ape-like arms would suffer discomfort no more. As it happened, professional wrestlers began filming their bouts in a TV studio across the street. These giants soon discovered the store of their dreams. They would also often head over to eat Stella’s steak and cabbage rolls. Gilbert would meet the likes of Hulk Hogan and André the Giant. The store still displays signed black-and-white prints of forgotten wrestlers, portraits from a bygone era.

Someone who entered the store looking for socks often walked out with a suit, and Gilbert never let a customer leave without a perfect fit. He dressed fastidiously in shirt and tie, and was always festooned with the tools of his trade: a thimbled finger, tape measure dangling around his neck, needle and thread attached to his breast pocket. He patted shoulders, bums and thighs to ensure requisite snugness. Alterations happened on the spot. Gilbert never looked at the clock; he worked until the job was done, which it never was.

Gilbert kept a Slavic accent and an idiosyncratic command of English. When he was told his son Tom had gone “cross-country skiing,” Gilbert grew agitated about him heading to the Pacific coast by foot. On days Stella displayed some bust, Gilbert would say, “Stella, I love your Cleveland.” He smoked La Palina cigars and used them to wake up his teens for school—Gilbert on all fours, blowing smoke under their bedroom doors. He’d offer his kids’ friends a dollar to do chores like wash the store windows—“If you do job, I give you buck.” When they inevitably failed to meet his standards for industriousness, he exlaimed “new generation!” with an incredulous headshake.

Stella and Gilbert worked side by side, year after year, until the aging couple found themselves serving the grandchildren of their first customers, in a store that had expanded fourfold to 8,000 sq. feet. Retirement was never an option. Gilbert told his wife, “they’re going to have to carry me out of here.”

On Aug. 1, Gilbert headed for the store’s basement toting a few yards of navy blue cloth. He ducked as he descended the narrow flight of stairs to the stockroom. His son Tom heard a step, followed by a pause, then another step. Then a bang. It took four men to carry Gilbert back up and onto a gurney. He was rushed to hospital, where he died of heart failure. He was 84.