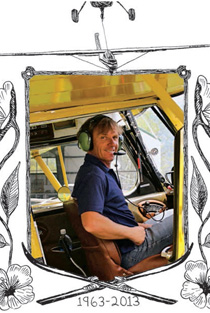

Rudolf Rozsypalek

He fled Czechoslovakia for a better life in Canada. An expert glider pilot, even an astronaut once sought out his instruction.

Greg Sorenson; Illustration by Team Macho

Share

Rudolf (Rudy) Rozsypalek was born on March 27, 1963, in the small Czechoslovakian town of Uherske Hradiste, which sits in a valley that is home to the country’s aviation industy. His father, Rudolf, worked as a radio operator in the military, and his mother, Eva, worked in a Bata shoe factory. He had an older sister, Ilona.

Even as a young boy, he dreamed of a life free from the reach of Soviet influence. He talked of living in the wild mountains and forests of Canada. When he was 15, he began flying gliders at the nearby Kunovice airport. He learned to chart flights with military precision, for those times when the sky was too heavy with pollution to navigate by sight, and he dreamed of opening his own gliding school. He spent the winters cross-country skiing, wearing a jacket he sewed himself. Rudy completed his mandatory two years of military service, then studied horticulture and worked as a truck driver.

In the spring of 1989, desperate to escape Communist rule, he booked a flight to Cuba via Montreal. When the plane landed in Montreal on April 4, he jumped off, locked himself in the airport bathroom until the flight left and claimed refugee status. Five months later, the Iron Curtain fell. Fearing that he’d be sent home, Rudy hitchhiked across Canada, reaching Vancouver in September, where he eventually gained landed immigrant status. Speaking only a little English, he worked construction jobs for fellow Czechs until he joined the Vancouver Soaring Association and met fellow pilot Peter Timm, a landscaping contractor. “He knew his botanical names for plants,” Timm recalls. He hired Rudy on the spot.

Rudy amazed his fellow flyers from day one. On a test flight to prove he could land safely if the tow rope pulling the glider broke at a low altitude, Rudy calmly asked his co-pilot, “Do I have to land now?” and instead, he found a bit of lift to send the plane soaring.

On Nov. 11, 1990, Rudy’s roommate invited his girlfriend over to their New Westminster home, and her sister, 24-year-old Tracey McCutcheon tagged along. She says he was “a real manly man,” with sparkling eyes, a sideways smile—and thick, blond, unruly hair, which he only cut once a year. Rudy showed her a picture of himself standing on a mountaintop. “I fell in love with him,” she says. They moved in together about a month later, finding an apartment with a rooftop patio view of Mount Baker.

In 1993, Rudy and Timm decided to tackle Rudy’s dream to open a gliding school: Pemberton Soaring Centre in the Pemberton Valley. They drove to Cape Cod to buy an $8,000 Blanik glider with red Soviet stars on its wings—made in the same Czech airport where Rudy learned to fly. Rudy and Tracey lived in a mobile home at the airport for the next 11 years. For an office, they pitched a big tent, and around it Rudy built a deck and arbour over which he grew grape vines. The fridge would be open, stocked with Czech pilsner and surrounded by pilots shooting the breeze, says one of Rudy’s first customers, Nigel Protter.

Rudy married Tracey at the airport campsite in 1995. He would often say, in his Slavic accent: “I came to Canada to find Tracey.” Their first son, Thomas, was born in 1998. Troy was born in 2000. Timm and Rudy bought more gliders, more planes to tow them and hired more pilots. In the off-season, Rudy skied Whistler’s steepest slopes alongside his sons.

In 2004 the family moved into a house in a nearby subdivision. By then, Rudy had taken over the business from Timm and built a large steel hanger. It was called the Pemberton Airport, but “it was actually Rudy’s airport,” Protter says. “Everyone trusted his instincts and knowledge.” All manner of pilots sought out Rudy and his gliders: fighter pilots, commercial airline captains, even an astronaut. Rudy called gliding a creation of constant changes in speed and direction, and compaired it to the lines of a painting.

On the morning of June 29, Rudy hugged Tracey goodbye. He told his sons to have a good day, and went to the airport. A tourist from India showed up for a glider flight. They took off under the late-morning sun and clear skies. The airspace above Pemberton is uncontrolled: pilots communicate by radios and navigate by sight. At 12:19 p.m., Rudy’s glider and a Cessna 150 carrying two people and a dog collided in mid-air. Debris rained down on the campsite below. No one survived. The crash is now under investigation. Rudy was 50.