Revenge of the arts: Why a liberal arts education pays off

New uOttawa research challenges the age-old rhetoric around “soft skill” degrees

Professor Ross Finnie is photographed in his office at the University of Ottawa. (Photograph by Jessica Deeks)

Share

Author Margaret Atwood; TV host Alex Trebek; Prime Minister Justin Trudeau; Hootsuite founder Ryan Holmes; actor Donald Sutherland. The common thread here is none other than the much maligned liberal arts education.

Now the latest research out of the University of Ottawa’s Education Policy Research Initiative (EPRI) proves that a degree or diploma in the social sciences or humanities pays off in the long run.

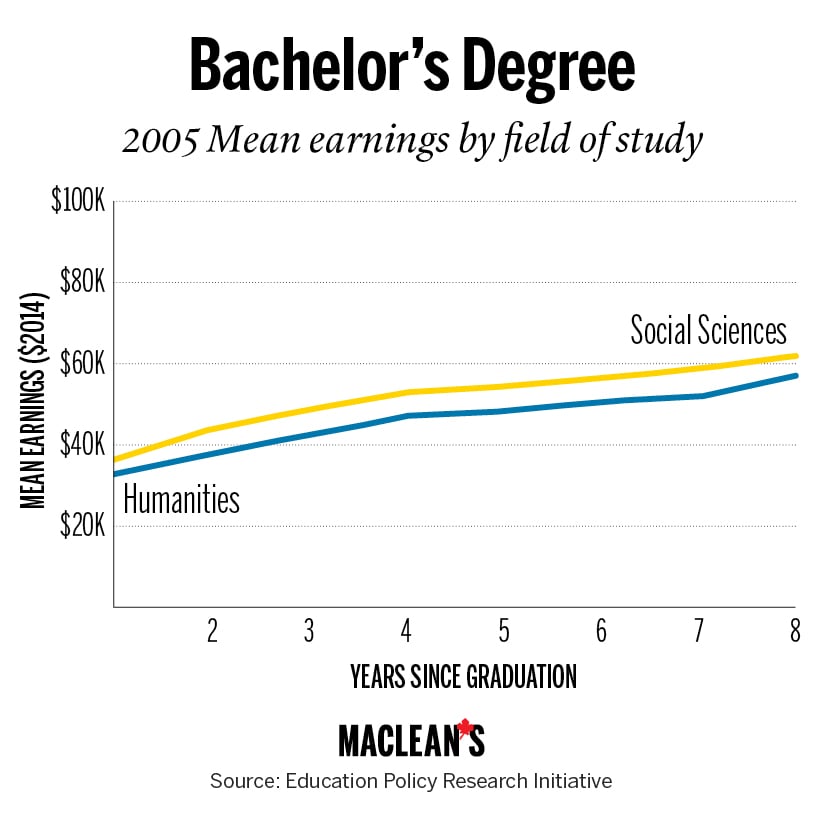

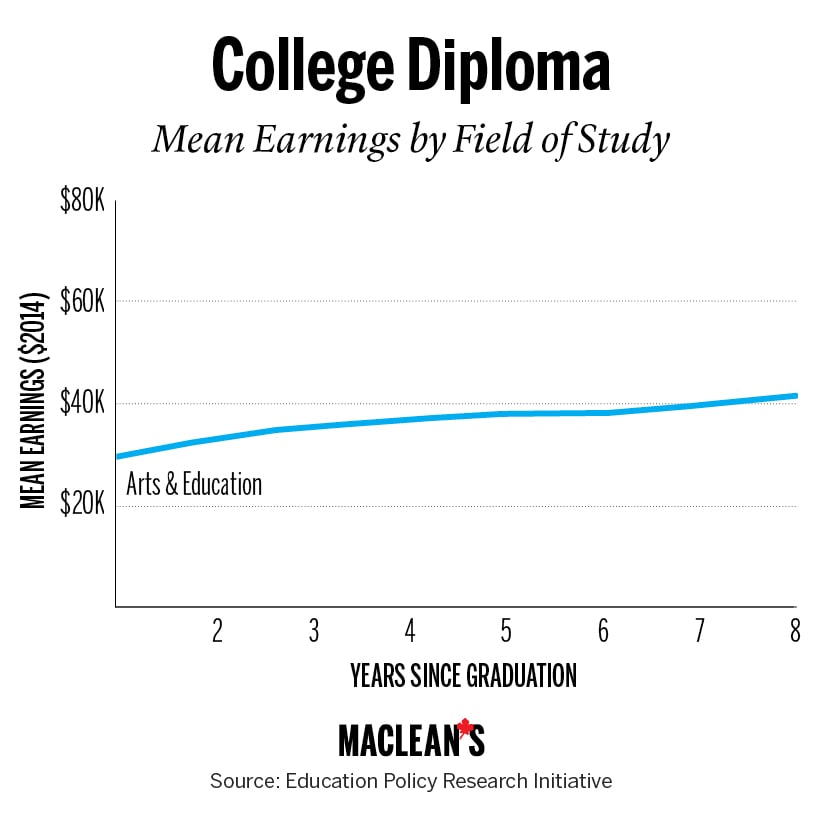

After linking income tax data with administrative data on 340,000 students who graduated between 2005 and 2013 from eight universities and six colleges, director Ross Finnie and his team showed that eight years after graduation, a social-sciences degree holder earned $61,900 on average, while humanities grads brought in $57,000. In diploma programs, offered at colleges, arts and education graduates earned $41,500 after eight years. The liberal arts or humanities are the study of the human condition, and refer to disciplines like philosophy, history, literature, and psychology, while social scientists study human behaviour in fields such as economics, psychology, sociology and law.

The findings challenge the age-old rhetoric around a liberal arts education: That a degree or diploma in the field leads to a minimum-wage job.

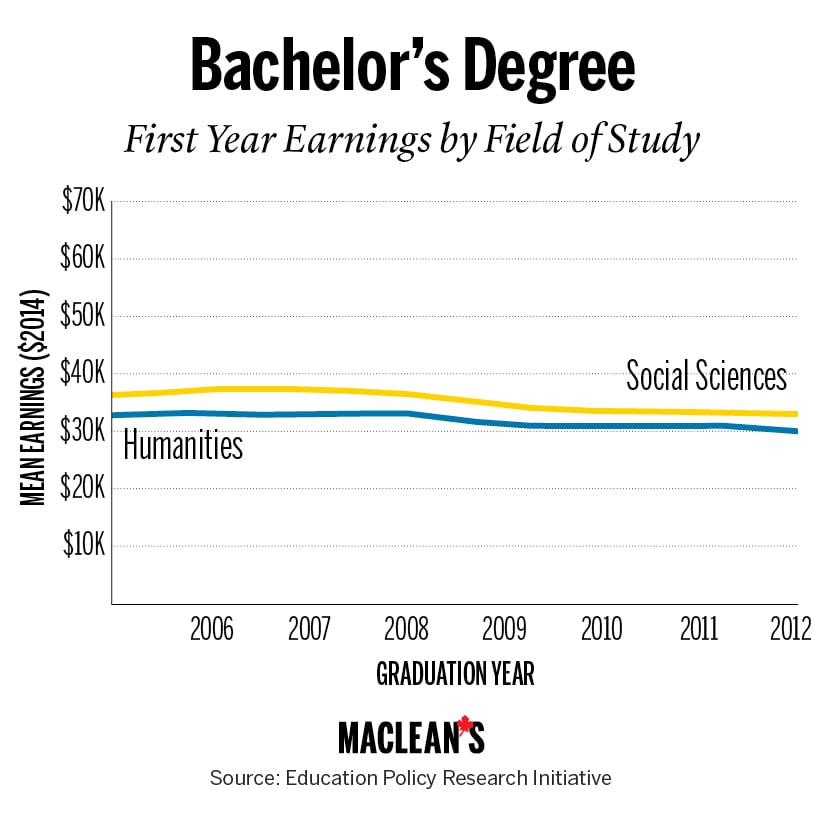

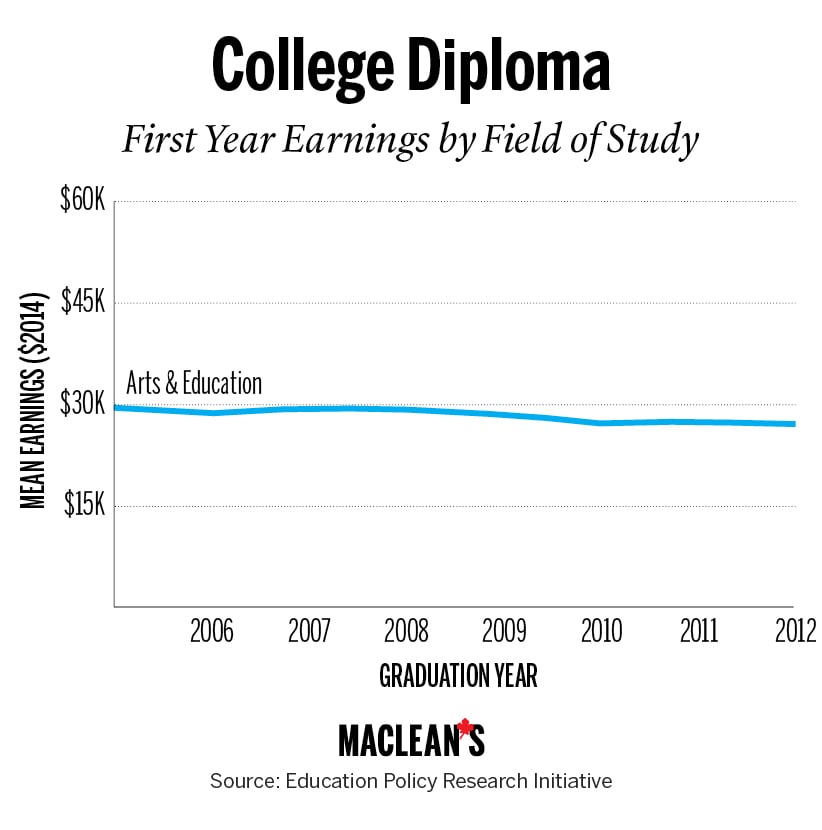

According to the aggregate data, in the first year after graduating from a degree program, social science grads earned an average of $36,300 and humanities grads $32,800. That rose by an average yearly increase of $3,700 and $3,500 respectively. In diploma programs, arts and education graduates earned $29,600 in the first year, with average yearly increases of around $1,700.

“It’s not that they studied Plato or Aristotle,” Finnie says, “but it’s that they probably learned critical thinking or problem solving. When people go into the labour market they are doing okay, so those skills must be worth something.”

He says more research can help pinpoint the soft skills and figure out how post-secondary institutions can help develop them. “If we identify those skills, we can measure them, or the factors underlying them … this could be the future, I think, of saving the humanities and social sciences,” Finnie says.

Soft skills are increasingly in demand by employers. In a recent survey of 90 large, private sector companies in Canada, the Business Council of Canada found 67 per cent valued teamwork as the most important skill in an entry-level candidate. Communication, problem-solving and people skills were also at the top of the list. “There’s a world of possibilities,” says Paul Davidson, president of Universities Canada, which is an advocate for 97 institutions across the country. “Many of the jobs that are going to exist in five years haven’t been invented yet. Having a skill set that is broad, and being able to read, write, think, and speak—those are enduring skills.”

Since 2008, enrolment in social sciences and humanities programs in Canada has dropped, in some places by as much as 20 per cent, Davidson says. This is likely because of global economic uncertainty and the emphasis placed on STEM—science, technology, engineering, and math—over the past couple of decades by governments. Even Prime Minister Trudeau made a campaign promise of $40 million for employers to create co-op placements for students in STEM programs, and made no similar promise for liberal arts students.

The federal government has, however, promised $200 million a year for the next three years for its innovation agenda, which focuses on six areas. Jean-Marc Mangin, executive director of the Federation of Humanities and Social Sciences, says the liberal arts are present in all six.

“They don’t see social science and humanities as a nice add-on, as a luxury, but as integral to their way of thinking and developing an inclusive and dynamic society moving forward.” Mangin feels the “cultural siege” that’s been corroding liberal arts is finally lifting.

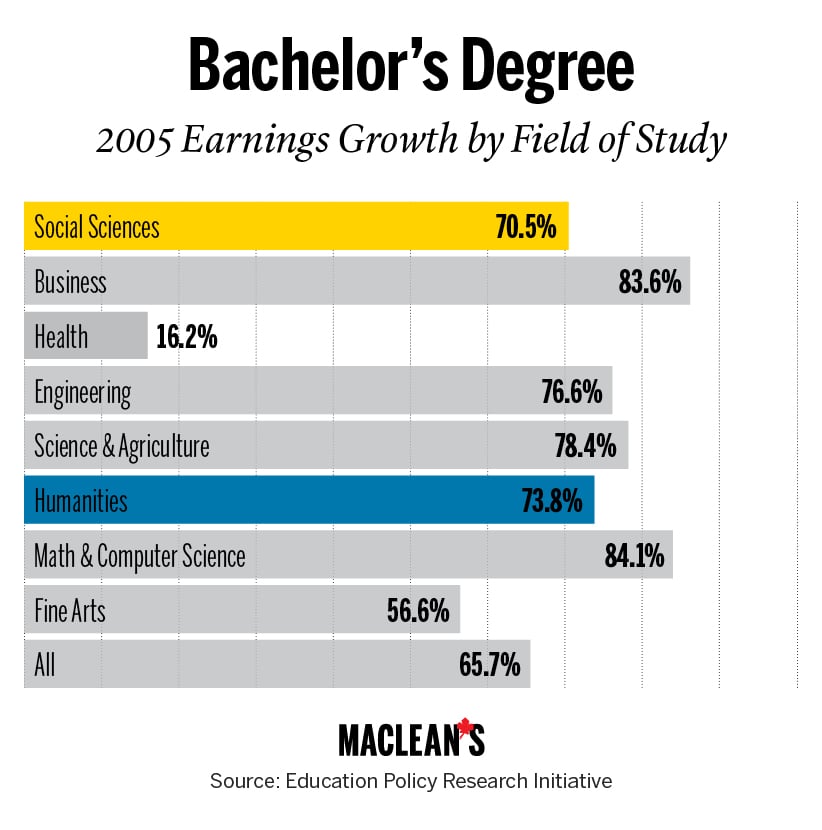

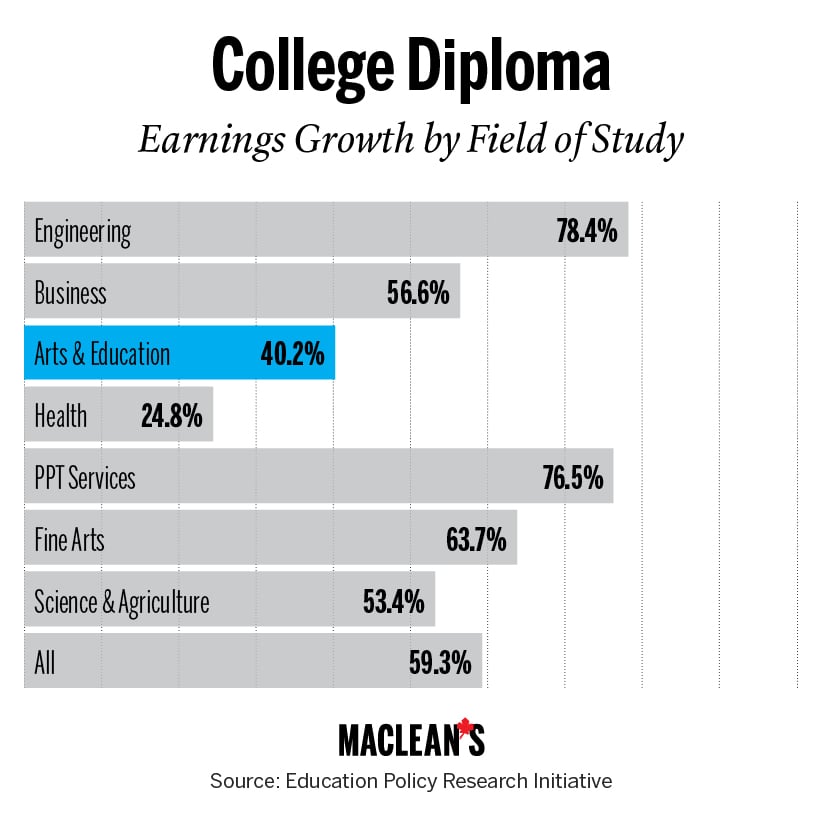

Despite the long-term potential of a liberal arts education, according to Finnie’s research an engineering degree still leads to the highest earnings. After eight years, 2005 graduates earned nearly $100,000 a year. Math and computer science grads with degrees follow close behind. Trailing at the end are those in the fine arts, who made just over $45,000 eight years out of school. Grads with an engineering diploma also topped the list on the college side, making around $72,000 eight years out, while grads with a fine arts diploma earned around $41,000.

Although men graduating from degree programs in 2005 earned only $2,800 more than their female counterparts in their first year, after eight years the wage gap increased by 44 per cent to $27,300. In the health degree sector, the EPRI team noticed that while women started with higher earnings than men, their salaries flat-lined, while men’s earnings grew steadily. Finnie says these trends could be attributed to a combination of factors, including differences in occupational choices between men and women, prioritizing family, and, “finally, pure labour market discrimination.” The wage gap was even larger in the college diploma cohort, with men earning 56 per cent more than women after eight years.

Unless the institutions decided to release the information publicly, a school by school comparison of the data is not possible, and that is precisely what schools want to guard against. Because a university is different from a college, and each offers different programs and serves a different population, they feel a direct comparison is not fair. “One way or the other, [a school] runs the risk of not looking as good,” Finnie says.

At the moment, the only comparison that can be made is between Finnie’s previous data from a 2014 study of U of O grads. For example, the first-year earnings of a 2005 humanities grad at the U of O was $38,300, $5,500 more than the first-year earnings of an average 2005 humanities grad from the eight universities in the newest report. By 2010, the year the original U of O data ends, the Ottawa grad was earning $59,000 and the aggregate grad was earning $50,500.

RELATED: New research shows which degrees lead to high-paying jobs

“Our local Ottawa market is more skewed toward the public service and federal government in particular,” Finnie says. “It just points towards why we need a broader analysis, and ideally, we’d be doing this for the entire country.

Finnie says this report is just the first step, and looking at how the earnings of grads from one school compare to another could be done in future research. He adds that other factors need to be considered, like the characteristics of the students and the labour markets the students are entering, before comparisons can be made.

View EPRI’s interactive graphs here.