2016 teaching awards: These professors are at the head of the class

Get out your catalogues and try to nab a course with one of the best university teachers in the country

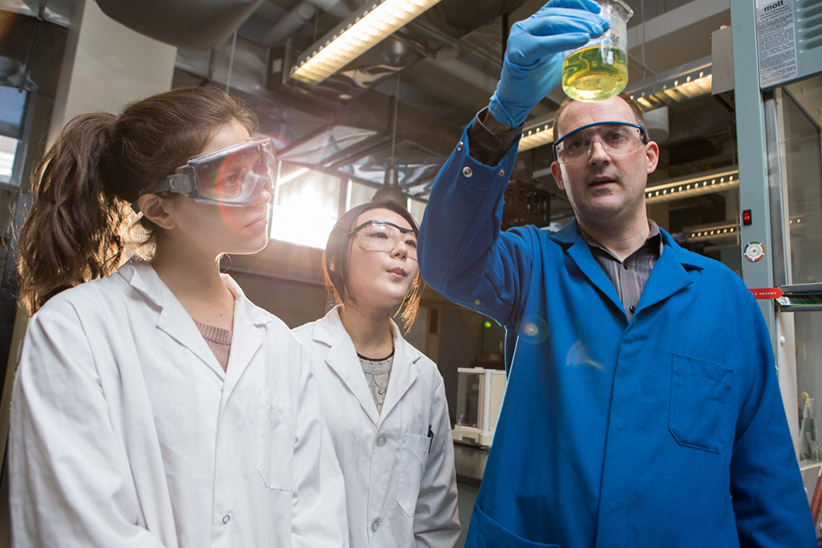

Professor Andy Dicks is photographed in his University of Toronto chemistry lab. Dicks is one of 10 winners of the 3M Teaching Award. (Photograph by Jennifer Roberts)

Share

The 3M National Fellowship Award comes with no money attached, but the prestige is its own reward, as universities trumpet their winners and Maclean’s considers the awards as a part of its measure of faculty success in its annual University Rankings. For 30 years, the award has been bringing together 10 teachers every year (save for the year it awarded eight) —a total of 298 since it started—to a conference, as well as an annual retreat in Banff, Alta., in November.

“Leadership in education can be a very lonely thing,” says University of Prince Edward Island English professor Shannon Murray, the coordinator of the award and a 2001 fellow. “You have to be a trailblazer, and the emphasis in many universities is toward scholarship and research.”

This year they will gather at the Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education conference at Western University in June. “It’s like summer camp for university professors,” says Murray. The fellows are encouraged to share ideas and make new connections. “The fellowship gives them another community, so they can go on and do even more,” she says.

Andrew Dicks

Chemistry, University of Toronto

Dicks often finds students looking at a poster outside his office—the one about the chemistry of Christmas. It explains how hand warmers work, and the components of ginger cookies and pine needles. “It’s by far the most popular poster I have.”

That’s one way he shows students the relevance of chemistry in their lives, and that the subject, too often seen as dry, can be fun. It’s also evolving: Dicks practises green chemistry, a new field that involves trying to create more environmentally responsible products.

Unlike some other sciences, chemistry “is about problem solving,” says Dicks, and his classes reflect that. While traditional coursework has students memorizing chemical reactions and following instructions to carry out an experiment, “we’re interested in experiments where we give students a problem to solve, and they design a solution to it to test it out.”

They plan the experiment, see if it works, and figure out why it did—or didn’t. “Maybe only 70 per cent of the class plans and executes something that works, but the feedback that we get is that it’s a great learning experience,” Dicks says. “This approach is more fun, and more real, too.” The award-winning teacher has also been widely published, often with papers co-authored with undergraduate research students. “They are the lead authors on the papers, and I rely on them to come up with ideas and strategies.”

Amid all of this, however, he often focuses on solving problems that are decidedly unscientific. To help students, he gives a lot of one-on-one interviews, offering them guidance on personal challenges from long commutes to overwhelming midterm schedules. “My No. 1 quality is empathy,” he says. “I teach a lot of big first-year classes, and the transition to first year from high school is a huge one. That’s why I try not to overload them, and to make chemistry real and relevant and really interesting.”

Veronika Mogyorody

School of Creative Arts, University of Windsor

Mogyorody is an architect and urban designer who studies how the built environment affects learning; she sees herself as the interpreter for architects and faculty at the University of Windsor. They work together to create next-generation learning spaces, such as the Health Education Building, the Medical Education Building and the Centre for Engineering Innovation. “With the ubiquitous presence of various modes of technology, learning isn’t confined to traditional classrooms anymore,” she says. “It is an exciting time to be involved in the reimagining of what classrooms can be, and what role those informal spaces just outside the classroom door can play.” She also created a unique interdisciplinary visual arts and architecture program.

Allyson Jule

Education, Gender Studies Institute, Trinity Western University

Jule’s courses reward adventurous spirits. She travels with her students to Cameroon for three weeks, where they teach students, often by candlelight. “It is quite the thing to see teaching done in a totally different context,” she says. Closer to home, she’s combined faith and feminism by creating the gender studies minor at Trinity Western.

Andrea Buchholz

Family Relations and Applied Nutrition, University of Guelph

Buchholz’s teaching style is inspired by her hobby, improv theatre. “I try to break down the fourth wall separating me from students,” she says. “We learn actively together—real-time, in-the-moment engagement.” She also runs an optional “step-up” club, which is a study session for students who need extra help with the course work. Buchholz has created innovative classes, including “globesity,” a first-year seminar that looks at the worldwide challenge of obesity; reformed the school’s applied human nutrition program to be more student-centred; and designed the one-of-a-kind applied clinical skills course, which includes a nutrition-focused physical exam.

Ken MacMillan

History, University of Calgary

“I often tell students that an essay is like an iceberg,” says MacMillan. “I see the 10 per cent they commit to paper, but the other 90 per cent is the context, the research, the decisions about what to include made along the way.” He takes a similar approach to teaching, offering students the most interesting parts of any topic to lead them through large, dense subjects and hold their interest during lectures. His enthusiasm for history—which he describes as “a discipline that teaches empathy, a respect for lifelong learning, and the desire to be an active participant in society”—also keeps them engaged.

Then there’s his love of teaching. A big proponent of group work, MacMillan says “listening to the cacophony of [student] voices talking about the material in class—that’s really a great 20 minutes of my week.” He gives creative assignments, such as writing autobiographies of 17th-century Englishmen, or re-enacting historical crimes.

He also involves them as much as possible in his work—he even wrote one of his course texts, “Stories of true crime in Tudor and Stuart England,” with two of them. “Working with former students allowed me to get a better sense of how they consumed these texts, and the challenges they experienced, which helped me decide on the book’s format and how I might make the material more digestible,” he says.

When it all comes together in a great class, he can feel the buzz of excitement. “Sometimes you just know a class is going really well,” he says. “When you walk out, the students are talking about the material as they’re leaving the room, they’re excited. It’s a great feeling.”

Eileen Wood

Psychology, Wilfrid Laurier University

An early adopter of new technologies, Wood uses them “as a springboard for interactive group work” in her classes. “This is active, pertinent, and makes the information they are learning more real,” says the professor, who describes herself as “a beginner with experience.” She also developed a course for eCampusOntario, a portal for online courses at the province’s universities and colleges. Wood knows teaching and learning are intricately linked, and her students benefit. “When we get to the end [of class],” says one student, “I don’t even want to leave.”

Martin Schreiber

Medicine, University of Toronto

Schreiber is one of the most decorated teachers at U of T’s medical school, with more than 40 teaching awards to his name. He connects the work students are doing to real-life cases he’s seen, offers it in manageable chunks, and demands the best from his students, all with a healthy dose of humour.

Maja Krzic

Soil Science, Applied Biology, University of British Columbia

The award-winning teacher (13 accolades and counting) is passionate about soil. “It’s essential to our lives,” she says, ticking off its roles in our ecosystem: growing food, cleaning water, and even mitigating climate change. Her students collaborate with scientists, companies and non-profits, which enriches their knowledge and helps them imagine a career in the field. She also created a web-based tool, the Virtual Soil Science Learning Resources Consortium, now used in 37 post-secondary institutions worldwide.

Bruce Wainman

Pathology and Molecular Medicine, McMaster University

Wainman took the anatomy lab into the digital age with the MacAnatomy project, an online portal that gives students access to streamed lectures, digitized texts and other media, and a searchable catalogue of specimens. The site has now logged one million page views. “It was a huge opportunity to both help all of the students at McMaster and pay homage to the donors and anatomists who did the work,” he says. His aim is to present complex material in the clearest way possible, inspiring students with his passion. “The goal of my teaching is to make science as fascinating to my students as it is to me.”

David Blades

Curriculum and Instruction, University of Victoria

Blades teaches teachers how to teach science—a subject he believes is crucial to understanding the world, and to developing critical thinking skills. His educational model, Explore-Discuss-Understand, “incorporates the best elements of hands-on, inquiry approaches to science education.”

[widgets_on_pages id=”Education”]