Portrait of a young ‘honour killer’

How an old family photo could derail Hamed Shafia’s last-ditch appeal

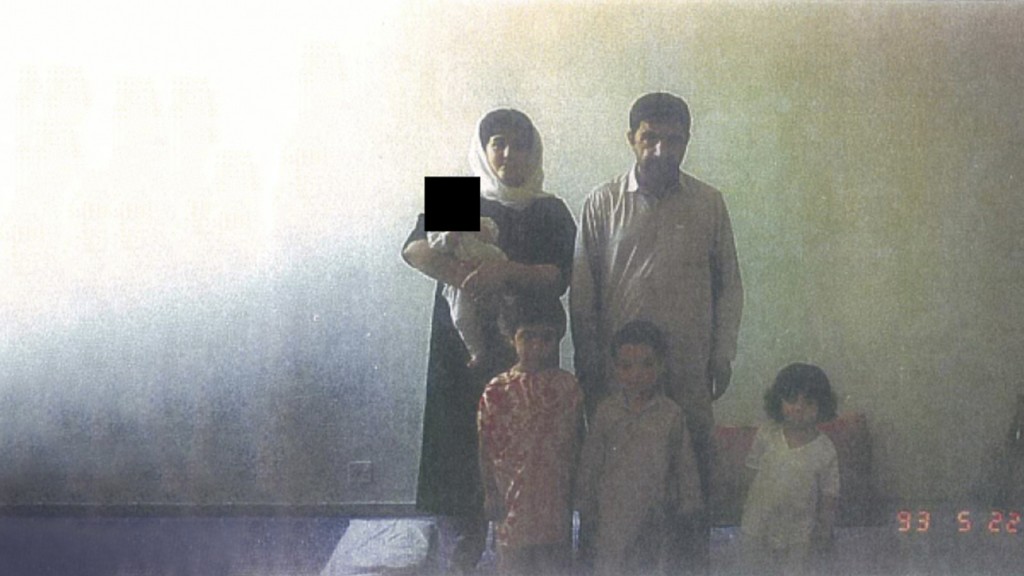

Shafia family photo from May 22, 1993. (Crown Exhibit)

Share

Given how the story ends, it is a haunting family photograph.

Date-stamped May 22, 1993, the grainy image shows an adorable-looking Hamed Shafia, still too young for school, sandwiched between two of the sisters he would one day conspire to kill on Canadian soil: Zainab, 15 months his senior, and Sahar, 10 months younger. Standing behind the three children are their Afghan parents—and Hamed’s future accomplices—Mohammad Shafia and Tooba Yahya.

The picture was snapped in Peshawar, Pakistan, not long after the family fled the civil war raging in their home country next door. Yahya has a white hijab wrapped around her head and a baby in her arms. Her husband’s shoulders are slightly slouched, his hands at his side as the camera clicks.

Sixteen years later, after the family immigrated to Canada, police in Kingston, Ont., would find Zainab and Sahar stuffed inside a sunken car at the bottom of a Rideau Canal lock station. They were not alone. Divers also recovered the bodies of Geeti Shafia, another sister who was not yet born when that portrait was taken; and Rona Amir Mohammad, Dad’s first (and infertile) wife in their secretly polygamous clan.

What happened to those women is no longer in dispute (and never really was). The sisters were “whores” (in the warped worldview of their dad, as captured on police wiretaps) whose stylish clothing and secret boyfriends had so smeared the family’s reputation that only mass murder—designed to look like a tragic traffic accident—could restore that tarnished “honour.” Rona, long marginalized by her wealthy Muslim husband and her fellow bride, was a convenient throw-in, easily dispensable.

It took a jury just 15 hours to convict all three—father, mother and eldest son—of four counts each of first-degree murder. Now serving life sentences, the trio’s Hail-Mary request for a new trial was recently rejected by Ontario’s top court, cementing the verdicts. “Charitably put,” the appeal court concluded, “the evidence of guilt was overwhelming.”

But the high-profile case isn’t finished quite yet. In one last round of legal filings, Hamed alone is seeking leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada—and that old family photograph, long forgotten, suddenly looms as an important piece of evidence.

Here’s why.

Hamed’s pursuit of a Supreme Court hearing hinges on one claim: that he was 17 when his relatives were executed on June 30, 2009, not 18 as originally thought, and therefore should have been treated as a young offender—with all the inherent protections of the Youth Criminal Justice Act. He was a homicidal teenager, in other words, not a homicidal adult.

The distinction is huge, to say the least. By law, a youth convicted of first-degree murder cannot serve more than six years in prison—and even if prosecutors convince a judge to sentence such a youth as an adult, parole eligibility kicks in after 10 years, not 25. Which means, if Hamed really was 17 when he helped drown his sisters and his “aunt,” he’d either be sprung from prison immediately, or allowed to apply for parole within a couple of years.

He is now 26. Or 25, if his claim has merit.

Why is Hamed’s age suddenly such a mystery? Post-conviction, a man who works for Mohammad Shafia in Afghanistan purportedly stumbled upon Hamed’s “tazkira,” the main personal identity document in that country. Up until then, everyone in the family, Hamed included, said he came into this world on Dec. 31, 1990. The tazkira, however, listed a different birthdate: 1991, one year later. Shafia’s employee investigated further, requesting a “Certificate of Live Birth” from Afghanistan’s public health ministry; based on records kept by the hospital where Hamed was born, it, too, listed 1991 as his year of birth.

The Criminal Code permits an appeal court to accept fresh evidence when it’s “in the interests of justice to do so,” as long as—according to a well-established legal test—the new evidence is relevant, credible, and could potentially alter the outcome of a case. At the Ontario Court of Appeal hearing last year, Hamed’s lawyer, Scott Hutchison, argued that the newly discovered documents do indeed pass that so-called Palmer test because they raise the real possibility that a young person was tried and convicted in a court that had no jurisdiction to preside over his case.

READ MORE: Shafia honour killers lose bid for new trial

The appeal panel disagreed, in large part because the three judges did not consider the new material “compelling.” Writing for the unanimous court in November, Justice David Watt said “the origins of the tazkira are inherently suspect” because the only information about how it emerged comes from the “hearsay evidence” of Mohammad Shafia, a quadruple murderer and serial liar. Watt also noted that Hamed’s mother, Yahya—the one person who presumably knows exactly when her beloved son was born—has repeatedly said, to police and the jury, that Hamed was 18 at the time of the crime.

“The idea that an individual may be unaware of their own birthdate might sound odd to Canadian ears,” reads Hamed’s memorandum of argument, filed with the Supreme Court. “But considered in its proper cultural context, and the turbulent history of the [Shafia] family as refugees from the wars in Afghanistan, it is readily understood.”

They fled to Pakistan in 1992 without any government documents, the memorandum says, and after living in Peshawar for three years the family was on the move again, this time to Dubai. “It is at this point that the inaccurate birth year was introduced,” the filing continues. “At the consulate in Peshawar, Afghan officials wrote in the year of birth of the children in Tooba’s passport”—including Hamed’s, as 1990, not 1991.

“The error in Hamed’s birthday was not the only error included in these forms or related documents: the years of birth of other Shafia children were also recorded erroneously, and the family name was misspelled as ‘Shafia’ instead of ‘Shafi,’ ” the brief goes on. “All of these errors (the various dates and the misspelled names) were repeated in subsequent documents and persist on the Shafia family’s official papers.”

Indeed, if Hamed really was born in 1991, it would mean the three siblings who arrived right after him—in successive years—are also 12 months younger than originally believed. Sahar, whose gravestone marks her birthdate as Oct. 22, 1991, would have been born in 1992, according to this new version of the truth. Another daughter supposedly born in 1992 (S.S., who cannot be identified because of a court-ordered publication ban) would have actually arrived in 1993. Same story for the next in line (a brother, A.S., who also can’t be named.) Although he grew up assuming he was born on Nov. 28, 1993, his family now insists his real date of birth is Nov. 28, 1994.

Which brings us back to that blurry family photograph—which the Crown made sure to include in its 62-page Supreme Court filing opposing Hamed’s leave to appeal. If the date stamp on the bottom right corner is correct—and nobody on either side has suggested it isn’t—the image is arguably the biggest blow to Hamed’s new birthdate scenario.

In fact, the photograph appears to depict exactly what the Shafias had long maintained pre-conviction: that Hamed, born Dec. 31, 1990, would have been about 2½ years old in May 1993. That Sahar, clearly able to walk when the photo was taken, would have been exactly 19 months. And that baby S.S., safely in her mother’s arms, would have been five months old.

How does the photo stack up to the revised timeline? The little boy in the front row would be 1½, not 2½. Although that may be possible, the child looks closer to 2½. Sahar? She would be just seven months old in the picture—yet able to stand up on her own. And baby S.S. (her face now blacked out to protect her privacy) wouldn’t be in her mother’s arms at all. She would be inside her womb, still seven months away from delivery.

“The fresh evidence is not credible, and it would not be in the interests of justice to admit it under any test,” reads the Crown’s memorandum of argument. “There is no merit to this application.”

The high court is still deciding whether to hear the appeal. A ruling could arrive any day.

Hutchison did not respond to an interview request from Maclean’s that included specific questions about the photograph. But his court filings make clear that his client believes the new evidence is credible enough to be sent back to a trial court, where a judge can decide what is conclusive and what isn’t.

“The Repsondent spends much of its memorandum re-arguing the facts,” reads his reply to the Crown’s brief, filed Feb. 17. “All this demonstrates is that there were two sides to this story, well-grounded in elements of the evidence…The Applicant deserves an opportunity to present this evidence in an appropriate forum—that is all he seeks.”