In Mexico, the USMCA means life goes on

With a new president, Mexico badly needed a trade deal with America, and it’s good that Canada is around—but the ‘new NAFTA’ elicits a collective shrug, and seems to change little

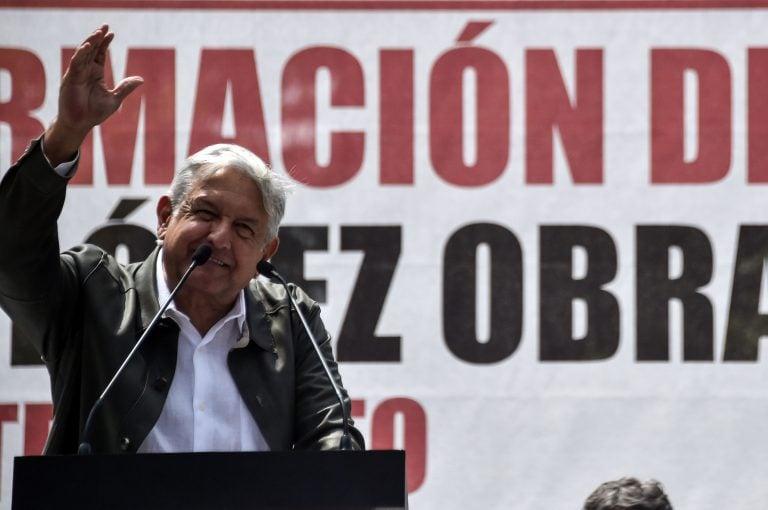

Mexican President-elect Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador waves to supporters during his national tour to thank those who voted for him in the July 1 elections, at the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Mexico City, on September 29, 2018. (Rodrigo Arangua/AFP/Getty Images)

Share

The name of the newly minted United States—Mexico—Canada Agreement doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue in English—much less in Spanish. And unlike the old NAFTA acronym in Spanish, TLCAN (pronounced: tele-CAN), the new USMCA is an especially tortured tongue-twister. In fact, there still isn’t an official Spanish acronym—something Mexicans had fun with on Twitter as they mocked it, proposing everything from the alphabet soupish AEUMC to the tawdry-seeming yet clever MEXICANUS (which translates to “pertaining to Mexico”).

But even though the new trade deal topped political and business agendas, and was so important that the Mexican government—which reached a deal with America first—was willing to cut Canada loose to do so, Mexicans largely met the news with a shrug. Grim stories about crime, corruption, and atrocities dominated the news cycle, as the deal landed on the eve of the 50th anniversary of the Tlatelolco massacre, in which soldiers attacked protesting students on the eve of the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. And even with NAFTA representing 80 per cent of Mexican exports, renegotiations and Donald Trump himself had actually sparked little chatter in the presidential elections, which left-wing populist Andrés Manuel López Obrador (also known as “AMLO”) won in a landslide.

Mexican opposition to NAFTA has lain dormant for years, as corrupt unions work in concert with companies at the expense of workers, poor farmers (campesinos) linger forgotten in the countryside even as agricultural exports hit record levels, and the Zapatista rebels—idealized on the left for their 1994 uprising that coincided with NAFTA’s arrival—now roil in irrelevance. Mexicans also have embraced the trappings of American culture and consumerism flowing south with free trade, to the point that long lines form outside pedestrian American restaurants like IHOP and tickets to the annual NFL game in Mexico City sell out in an hour.

And any buzzy news around USMCA in Mexico came mostly from spent forces. Outgoing Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto, for instance, told reporters Tuesday the new agreement was the product of his controversial mid-campaign invitation to then-candidate Donald Trump. According to Peña Nieto, the controversial meeting—in which he appeared to acquiesce in the presidential palace to Trump, was contradicted by Trump at a rally just hours after their meeting, and prompted a plunge in his polling— “left something very positive. It opened a door. … so we could be able to have a fluid, close dialogue of mutual respect. … There are differences that we have, but in commerce, we’ve found a point of agreement.”

READ MORE: The inside story of how NAFTA was saved at the last minute

Still, the Mexican government’s desperation to do a deal—any deal—showed how dependent Mexico’s economy is on the United States, where Mexico sends 80 per cent of its exports. It also showed the transformation of an economy once so closed that candy bars were sold as contraband in itinerant markets to a manufacturing-for-export platform.

That Mexico would cast aside Canada to pursue a bilateral deal demonstrated the depth of the elites’ desperation, as well as the Canadians’ misread of Mexico, which wanted to reach an agreement ahead of the Dec. 1 presidential transition and didn’t have the patience for Canada’s habit of dragging out negotiations.

“Some people will say: ‘We threw Canada under the bus.’ No, Canada threw itself under the bus by not giving Mexico something better,” said Federico Estévez, a political science professor at the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico.

“We’re more vulnerable than Canada—that’s the key difference,” said Estévez, who described Mexico as “capital-poor” and reliant on a steady stream of investment. “The price tag we could pay is much higher than what Canada would face. Canada would not become Turkey, where the currency has plunged, in other words.”

Like Canada, Mexico didn’t have many options, even though the political and business classes blustered about rejecting a bad deal and going it alone if necessary. Trump’s arrival in office also revived the perpetual chatter in Mexico of turning south toward Central and South America, something the López Obrador administration promises to do; Mexico even ordered corn from Brazil to show it was serious. But breaking with the North American market has proven difficult as geography favours northward trade, and the infrastructure is set up to support that.

Even as López Obrador vows to look south, he expressed satisfaction with the USMCA. He highlighted a pithy two-point chapter, which keeps the oil industry under state control—long an obsession for his nativist supporters, who still consider the 1938 oil expropriation an act of sovereignty and self-respect, and see the 2014 reform to open the sector to foreigners as an act of treason.

Mexico’s president-elect previously expressed skepticism on NAFTA; he spoke in past campaigns of reworking the agricultural chapters, and railed against stagnant wages and low growth even in NAFTA boom states, as well as annual per capital economic growth barely topping 1 percent since 1994. But opposing NAFTA would have proved perilous as the agreement shifted power over the economy from the state to the private sector, Estévez says. López Obrador has also sought to moderate his image ahead of the July 1 election—he pointedly promised bankers there would be no expropriations and has tapped mainstream economists for positions in the central bank and the finance ministry—and so here he is, a happy warrior for free trade. “It provides macroeconomic certainty,” he said.

He also focused on the parts of the deal that require 40 per cent of the labour on vehicles to be done at a salary of at least $16 per hour. “A Mexican worker can make 10 times less than an auto worker in Canada or the United States,” López Obrador said to supporters at a Trump-style “thank you tour” in Guanajuato state, where four automotive plants have opened since 1994 or are under construction. “This difference will be reduced bit by bit and this [agreement] is going to help Mexican workers.”

Even as he supports the USMCA, López Obrador promises to pump billions of pesos into building up southern Mexico—which NAFTA barely budged from underdevelopment. But much like the country he will soon preside over, which didn’t linger long on the UMSCA, his rhetoric at the rally wended his way back to regularly scheduled programming. “We’re going to produce what we consume in Mexico,” the populist said. “We’re not going to buy abroad any longer.”