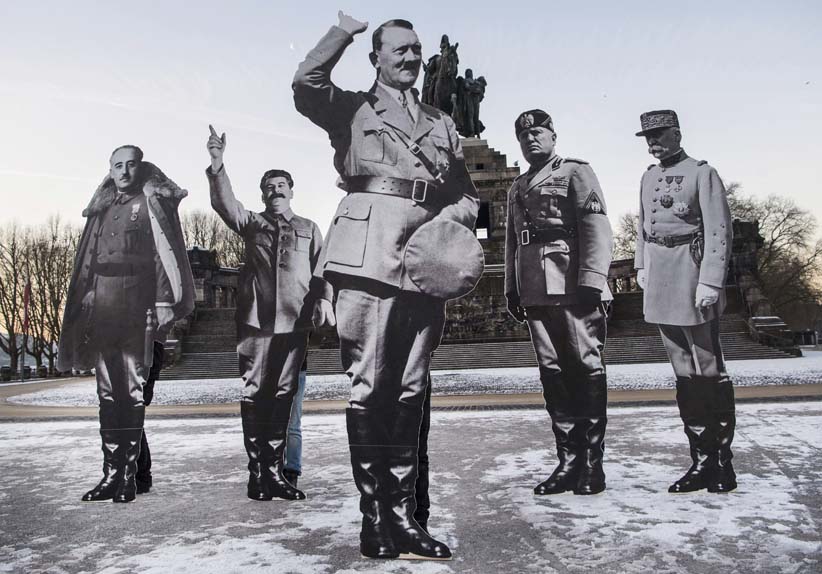

The meaning of a meeting of Europe’s leading nationalist minds

In Koblenz, Germany, the leaders of Europe’s nationalist movement unite for an awkward political spectacle

AfD (Alternative for Germany) chairwoman Frauke Petry, right, Far-right leader and candidate for next spring presidential elections Marine le Pen from France, center, and Dutch populist anti-Islam lawmaker Geert Wilders stand together after their speechesat a meeting of European Nationalists in Koblenz, Germany, Saturday, Jan. 21, 2017. (Michael Probst/AP/CP)

Share

At 6 a.m. on a Saturday morning in late January, a police squad entered a large conference hall in Koblenz, Germany and swept the place for explosives.

Outside, some 1,000 German police officers assumed formation around the perimeter. Near the front doors, an elderly man in a tweed coat told journalists that he had come to Koblenz because things in Germany were out of hand. His daughter, he said, was studying in Munich—and she couldn’t even walk safely alone at night. Because of those migrants.

Soon, the crowds arrived. Around 800 guests—almost all of them white and at least three-quarters male—filed into a large auditorium, where they were welcomed triumphantly to “a new Europe.”

So began a historic conference, which for the first time brought together leaders from Europe’s most formidable right-wing populist parties—including France’s Marine Le Pen (Front National), Netherlands’s Geert Wilders (Party for Freedom), Italy’s Matteo Salvini (Lega Nord) and Germany’s Frauke Petry (Alternative for Deutschland).

The timing of the conference was auspicious. In 2017, the Netherlands, France and Germany will all hold national elections; in each instance, nationalist parties are expected to do well. In Koblenz, the populist candidates came together with an unlikely proposition: that a handful of inward-looking nationalist parties can join together in a kind of Nationalist International—and forge a new pan-national nationalism in Europe.

The headliner of the day was Le Pen, who was introduced to attendees as “the next president of France.” In her speech, Le Pen called for a “Renaissance of Europe,” a revolt against neoliberalism, and “the defence of our national identities.” She presented the Koblenz parties as the last true defenders of national culture—against EU institutions that would, in her view, sacrifice France’s Frenchness, Germany’s Germanness and Italy’s Italianness to masses of Muslim refugees, eventually swallowing the states into a bland EU monoculture.

The increasing use of English by European leaders, Le Pen warned, is a sign of the “cowardice of our own elites who enable this capitulation of our cultures.”

A few days earlier, a survey by Ipsos Sopra Steria had named Le Pen—anti-immigrant, anti-Islam, famed for lashing out at “wild globalization” and the “elites” that feed it—as the favourite to win France’s presidential election in April. In the utopian dreams of European populists, a Le Pen presidency secures France’s exit from the European Union (Frexit), spurs a series of other Euro-exits across the continent and thus heralds the end of the European project.

Perhaps because Le Pen is polling so well, the mood in Koblenz bordered on estatic. The Koblenz auditorium was alive with chest-thumping music, blue stage lighting and howling groupies.

Following Le Pen on stage was the Netherland’s Geert Wilders—who compared the dismantling of the EU to the ‘Colour Revolutions’ of the ’80s and ’90s that brought down the Iron Curtain. “Yesterday, a new America, today Koblenz, and tomorrow a new Europe,” cooed Wilders. “The people of the West are awakening.”

MORE: The Canadian roots of white supremacist Richard Spencer

Throughout the day, party leaders nodded deeply to U.S. President Donald Trump. Several broke out of their national tongues to decry, in English, “fake news!” Geert Wilders announced his attendance on Twitter, with the hashtag #WeWillMakeOurCountriesGreatAgain.

But as much as they may appear like students of Trump, some of the represented parties have been around for decades. They are not so much inspired by the American president as buoyed by the twin victories of Trumpism and Brexit—in addition to the accession, in 2016, of the German AfD to the European Parliament group.

In many ways, the conference brought together parties that have little in common. Italy’s Northern League, for instance, is preoccupied with winning autonomy for Northern Italy—whereas Vlaams Belang promotes Flemish interests in Belgium. Germany’s AfD was started just four years ago, whereas Austria’s Freedom Party was founded by ex-Nazi henchman on the ruins of post-war Vienna. Wilders’ Party for Freedom supports LGBT rights, while German allies push conservative family policies. Indeed, leading up to the summit, senior AfD members criticized party leader Petry for agreeing to appear alongside Le Pen. “The FN is a socialist party,” protested Georg Pazderski, chairman of the AfD’s Berlin branch.

In Koblenz, the party leaders were united against perceived enemies: Islam, political correctness, globalization, and above all, the EU.

“There is a precedent to this,” says Cas Mudde*, of the University of Georgia’s School of Public and International Affairs. Mudde says that Europe’s right-wing populist parties began to collaborate seriously in the ’90s. But they struggled to meet the threshold for entering European Parliament—and were held back by “really extreme parties” who alienated voters with their thuggishness.

Things turned around in 2011, when Marine Le Pen wrestled control of the National Front from her father, John Marie Le Pen: a European pariah who famously dismissed the Holocaust as a mere “detail” of history.

“Marine Le Pen was good at selling an image of being more moderate,” says Mudde, and this “allowed other politicians to say, ‘The FN is different now.’ ” Around 2013, Le Pen formed a working friendship with Geert Wilders. In 2015, in an act of high theatre, Marine expelled her father and sent him into political exile.

Le Pen and Wilders soon recruited a crew of international populists: politicians who, generally speaking, signed on to the tacit requirement that they silence the crazed racists and rogue anti-Semites within their folds, and present themselves as acceptable faces of right-wing nationalism. Today, when these populist leaders speak of an evil, global cosmopolitan elite, they are probably not speaking in coded language about “the Jews”—as far-right parties historically did—but are instead referring to internationalist Eurocrats. Increasingly, the parties benefit from the refugee crisis, the euro crisis, and the near-moribund status of many European left parties.

The parties have also appropriated bits of leftist politics. Many combine anti-immigrant policies with support for the welfare state and a promise to protect women, Jewish people and homosexuals. Those in need deserve our help, only the refugees are sucking up all our resources and Muslims seek to destroy us, they say.

Of course, it wasn’t all treading softly in Koblenz. Geert Wilders opened his address with a chilling description of how the “population of Africa” is growing rapidly—supposedly leaving millions of black Africans intent on storming Europe.

In October, Wilders went on trial in the Netherlands on charges of hate speech and discrimination for comments he made promising “fewer” Moroccans in the country. Remarkably, Wilders—who has warned of an “Islamic invasion” of Europe—saw his popularity increase after his conviction. A recent survey by Peilingwijzer suggests that, in March’s national elections, Wilders’ party will emerge with the largest group in Parliament.

If Wilders does come out ahead, he is unlikely to win a majority, allowing other parties to form a coalition government. But even then, Wilders promised in Koblenz, “the genie will not go back into the bottle.”

Of the conference speakers, Germany’s Petry had the steeliest delivery. On the Koblenz stage, she described Germany as weakened and lacking in self-confidence: a country cowed by political correctness and historical shame. People feel guilty when they sing old, traditional songs, she lamented. And meanwhile, she suggested, “hundreds of thousands, millions, of mostly illiterate young men from a far and partly violent culture invade our continent.”

The AfD started four years ago as an anti-Euro party. It attracted moderate support—until the refugee crisis, which caused support for the party to spike. In 2013, Petry seized the leadership from Bernd Lucke, who later claimed that the AfD had been hijacked by pro-Russian xenophobes.

Following a spate of regional electoral victories last year, the AfD is now represented in 10 out of 16 state assemblies and polling around 16 per cent nationally. It is widely predicted to win its first seats in the German Bundestag this year: an extraordinary turn of events in a country that has, since World War II, been particularly averse to displays of nationalism.

Watching Petry keenly from the audience was Lorenzo Fontana, of Italy’s Northern League. Petry, Wilders and Le Pen “help us to understand that a new Europe is possible,” Fontana said in an interview. Global co-operation “is very important because the people . . . get awareness that our ideas are good and not extremist.”

Also watching was Gerolf Annemans, a member of the European Parliament and former chairman of Belgium’s Vlaams Belang. “It was superb,” Annemans told Maclean’s, of the conference. “We are rejecting this dogma of EU governors who say that it is either EU or war. As if they invented peace on the European continent. That is bulls—t . . . The Euro is a knife on the throat of all of us.”

But what exactly is “us”? Most of the party participants define themselves not as left or right, but using the fuzzier descriptor, “Patriotic.”

Increasingly, the term “far-right” feels out of date—better suited to the days when Jean Marie Le Pen was shrugging off the Holocaust and Austria’s Freedom Party was run by former SS officers. The word “populist” too is unsatisfying: carelessly applied to groups of nostalgic white men who take to the street and claim that they aren’t being heard.

In an afternoon press conference, Janice Atkinson, of Britain’s UKIP Party, attacked journalists for describing her as a “populist.” But she also said that she had consulted the Oxford English Dictionary and learned that populism “means representing the ordinary people”—and had thus decided that she was OK with the term. Ludovic De Danne, chief of foreign policy for the Front National, said in an interview that anyone who called the group “far-right” was “fake news.”

The Euro-populists are now looking further afield, in search of allies in Washington and Moscow. Several have already made overtures to Vladimir Putin, whose leadership they describe as a solid alternative to American hegemony. In December, Heinz-Christian Strache, of the Austrian Freedom Party, signed a cooperation agreement with Russia’s ruling party. Gianluca Savoini, who works with Italy’s Lega Nord as a liaison with Moscow, said in an interview that the Lega Nord will sign a similar deal this month. Le Pen has publicly declared Russia’s 2014 invasion and seizure of Crimea to be legitimate.

The day after the U.S. election, Trump met with Nigel Farage, former leader of Britain’s UKIP party and the architect of Brexit. The men were photographed in a golden elevator at Trump Tower, grinning like a pair of maniacs.

Last month, on Jan. 12, Le Pen was spotted in New York drinking coffee in the basement cafe of Trump Tower, where she met with Guido Lombardi, an Italian businessman who lives on the 63rd floor. A close friend of Trump, Lombardi also works as a kind of fixer for Italy’s Lega Nord party, introducing Italian populists to influencers across the pond.

In an interview, Lombardi insisted that Le Pen had come as his personal guest, and that he had thrown her “a little reception.” Denis Franceskin, a Front National representative in North America, said that Le Pen had also met with American business owners and civil servants. “I always think its funny,” Franceskin mused, “because if the FN was a party here [in America], they would probably all consider us Communists.” But times are changing, and the pioneers of this “new Europe” find kindred spirits where they can.

* Correction: A previous version of this post incorrectly spelled Cas Mudde’s name as “Cass Mudde.” Maclean’s regrets the error.