Canada is a tinderbox for populism. The 2019 election could spark it.

Opinion: This country isn’t immune to the economic and demographic forces currently dividing the United States

Ontario PC Leadership candidate Doug Ford, centre, poses for a selfie with supporters as he holds a campaign rally in Toronto on Saturday, February 3, 2018. (Chris Young/CP)

Share

Frank Graves is president of Ottawa-based EKOS Research Associates and a fellow of University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy. Michael Valpy is a senior fellow of Massey College and a senior fellow in public policy at University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy.

As Canadians, we sit atop the continent, watching as our neighbours slide into cultural civil war. It has become easy to just be appalled as America becomes riven, with social media and antagonistic rhetoric on both sides of the political spectrum erasing the middle ground. There are two Americas, incommensurably separated on the fundamental issues of the day: climate change, the economy, social issues like health and education, employment, the media, immigration in particular, and globalization and free trade.

We’ve learned more and more about the populism that has fuelled this complicated moment as the fracture in America races like wildfire throughout Western democracies. It is the biggest force reshaping democracy, our economies and public institutions. It is the product of economic despair, inequality, and yes, racism and xenophobia. It is an institutional blind spot, largely denied or ridiculed by the media, and by the more comfortable and educated portions of society.

It is very much alive in Canada. In fact, our populist explosion has already had its first bangs and is likely to have a major impact on next year’s federal election.

The shifts in the democratic world order over the last decade have increasingly prompted social scientists to discard the left-right political spectrum in favour of an “open-ordered axis,” or what The Economist calls drawbridge-down vs drawbridge-up thinking. The former are cosmopolitan-minded people, in favour of diversity, immigration, trade, and globalization, and who are optimistic about the future; they’re guided by reason and evidence-based policy, and believe that climate change is a dominant priority. Drawbridge-up people, with an “ordered” worldview, are largely parochial, and they have reservations about diversity, are deeply pessimistic about the economic future, believe more in moral certainty than reason and evidence, are disdainful of media, government and of scientific expertise, and are convinced that climate change is trumped by the economy and their own survival. It’s ordered thinking that is metastasizing in Western societies, including Canada’s, especially among the political right. EKOS research from 2017 suggests about 30 to 40 per cent of adult Canadians are drawn to it.

MORE: A carbon tax? Just try them.

Meanwhile, research over the last 10 years has found that Canada, like the United States, is turning into a society fissured along fault lines of education, class and gender. These are social chasms defined by the concentration of wealth at the top of society and, for everyone else, by economic pessimism and stagnation; by a comfortable feeling on one end of the societal teeter-totter, and a fear on the other end that a subscription to the middle-class dream might no longer be available.

Although there has been a recent uptick for the first time in 15 years, the portion of Canadians who self-identify as middle class since the turn of the century has declined from 70 per cent to 45 per cent, a stark number that mirrors America’s—signalling that Canadians have a deeply pessimistic view of their personal economic outlook. Only one in eight Canadians thinks they’re better off than a year ago. Only one in eight thinks the next generation will enjoy a better life. And EKOS finds that, by a margin of two to one, Canadians believe that if present trends with inequality continue, the country — this country! — will see violent class conflicts.

Ordered populism has already become an illusive, misunderstood theme in provincial elections in Quebec, New Brunswick, and Ontario. Indeed, Doug Ford and his Ontario Progressive Conservatives won thanks to a preponderance of working-class, male electoral support—but a closer examination of the vote shows that male millennials, against expectation, supported Ford in significant numbers and had a high turnout. Millennial women, meanwhile, preferred the New Democratic Party by a margin of 25 points, and the millennial women who didn’t vote NDP largely stayed home. Millennial men split their votes between the NDP and Progressive Conservatives, and they led females millennials by 10 points in turning out to cast ballots.

Survey evidence strongly suggests that these are young men angered by the economic realities they face, and they are hit the hardest by what is happening in Ontario’s economy. A joint study by United Way Toronto and York Region and Hamilton’s McMaster University on poverty and employment precarity in southern Ontario reports that only 44 per cent of millennials in the region — the heartbeat of Canada’s economy — have full-time, permanent jobs, that the majority have not found work that provides extended health benefits, pension plans, or employer-funded training, and that formerly high-paying blue-collar jobs there are rapidly vanishing. The lack of good jobs, coupled with the social catastrophe of affordable housing and the resulting need to delay family formation, is resulting in anxiety and depression that disproportionately affects millennial men—making them ideal targets for the appeals of ordered populism.

MORE: How should Andrew Scheer talk to Canadians?

What is happening challenges the conventional view that the youngest adults of Canadian society—the millennials, now Canada’s largest electoral demographic—operate with roughly similar, progressive views and values.

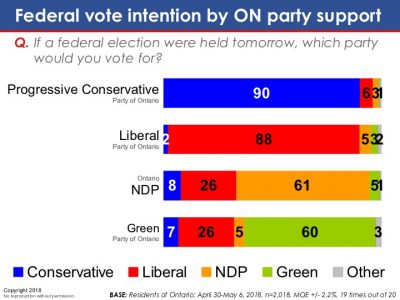

Another assumption in need of challenging is the idea that Canada’s ordered populism, like its American counterpart, is a besieged white citadel. In fact, our northern brand is as much the choice of multicultural new Canadians as of white native-born Canada. A significant chunk of new Canadians, many of them non-white, indicate they will vote Conservative in next year’s federal election — even though 65 per cent of Conservative supporters told EKOS this year that Canada admits too many non-white immigrants. And while a majority of Canadians are open to immigration, the intensity of the opposition is red-hot, including in other parties: 20 per cent of New Democratic Party supporters and 13 per cent of Liberal supporters also believe too many non-white immigrants are entering the country..

There are two possible explanations for this: First, new Canadians may bring with them into the country strains of social conservatism that make them hostile to issues like same-sex marriage and what they see as immoral, too-liberal sex education, an inflammatory issue in Ontario over the past couple of years. Thus, what they see as an assault on their values may be more important than a party trying to appeal to voters who want fewer of them in the country.

Second, where neighbourhoods are ethnically homogeneous as many are around the core of Canadian cities—white, brown or otherwise—populism holds appeal. Where there’s more diversity, it doesn’t. As social scientists have discovered, communities which have the least contact with with minority groups are the most hostile to them.

The looming federal election could be a spark for all the populist tinder largely being ignored in Canada. In the 2015 federal election, voting differences by gender for all age groups were flat. Now the federal Conservatives hold a 17-point advantage among men from all age groups other than seniors —a huge change in three years. Federal Conservatives also hold an advantage over Liberals and New Democrats with voters who self-identify as working class, and the party has overwhelming support from non-university-educated Canadians, the group most likely to feel left behind by the disappearance of blue-collar industries.

Former Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper led a party supported by the economically comfortable. His successor, Andrew Scheer, leads a party of the economically unhappy, of the new economy’s losers, a base increasingly comfortable with raising the drawbridge even as the Liberal government announces Canada will admit an additional 40,000 immigrants by 2021, bringing the annual number of new, mostly non-white arrivals to 350,000. Any campaign rhetoric that confuses this new support with its old party will only exacerbate the anger—and for the angry to find comfort in populism’s temptations.

What we do know is that Ontario’s Progressive Conservative government, with its populist strains and its vague campaign promises, is what many angry young men voted for. Maybe they didn’t vote for its policies; maybe, in their anger, they just voted to burn the house down, even if the history of populist movements show they’ve rarely worked out.

We can try to understand why it’s happening. We can insist that governments tackle inequality and affordable housing. We can build a future that preserves progress for all of us but addresses the real injuries of those who have embraced populism, while also refusing to bend to their fear, anger and ignorance. But letting populism burn the house down benefits nobody—and we can’t just ignore the smell of gasoline in the air.