Canada’s science minister speaks out on women in STEM

Kirsty Duncan is considering quotas to ensure women land top research posts. Is the Trudeau government on board?

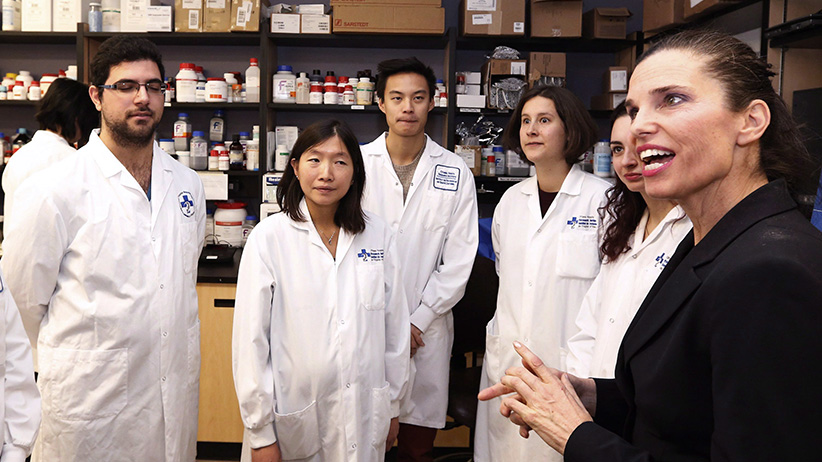

Minister of Science Kirsty Duncan meets with stem cell researchers after announcing $2.2-million funding towards Stem Cell research at the Ottawa Hospital, Thursday, November 24, 2016. (Fred Chartrand/CP)

Share

This week, Canada’s Minister of Science Kirsty Duncan made headlines when she expressed frustration over the fact female scientists occupy only 30 per cent of the 1,612 positions in the Canada Research Chairs Program (CRCP). “Dismal,” is how Duncan, a former research scientist and university professor, referred to the stat. She also said she was open to “forcing the issue” with universities in order to achieve greater gender parity.

Duncan spoke with Anne Kingston about the obstacles women face in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, mathematics), what needs to be done to increase gender parity, and why quotas could be an answer.

Were the CRCP stats a tipping point moment for you, or is the notion of “forcing the issue” something you have been considering?

This has been on my radar for a long time. When I was at the university I fought to increase the role of women in science. Since taking on this role, I’ve been speaking about it publicly. The landscape in academic science is traditionally male-dominated. Women didn’t always see themselves there—there was a lack of role models, a lack of champions. It really helped when the Prime Minister appointed a gender-balanced cabinet. That was well-received and people realized that, if the Prime Minister could do it, why can’t there be equity other places? It’s an issue that has been growing for a long time. A lot of women have worked a long time to increase the role of women in STEM.

Just for context: two days ago, on the way to a speech [to university presidents in Montreal], I got data on the latest round of nominations from the Canadian universities for the Canada Research Chairs and it was dismal. There was an update yesterday and I received more bad news. This has not been reported. The upcoming round of nomination results is just as bad. Two times the number of men over women are being nominated. I don’t think universities are taking equality issue regarding the CRC seriously enough. It’s not acceptable, and I’m not going to accept it.

What might “forcing change” look like? Are we talking quotas?

Duncan: The Naylor Report [Investing in Canada’s Future: Strengthening the Foundations of Canadian Research] is the fundamental science review we’ve just done; a review had not been done in 40 years. The panel suggested I consider quotas. So I am looking at my options. I’m working with the Social Sciences & Humanities Research Council because they administer the program. The bottom line is that the universities have to create an environment where more women are applying and more women are being nominated.

You’re part of the country’s first female-male balanced cabinet, yet your government has also shown reluctance to legislate quotas. Does your talking about doing so signal change in that regard or is it singular to this file?

Right now I’m looking at what options I have. There are tremendous women researchers who deserve a shot.

The stats for the CRC program stats are actually higher than those for women’s participation in STEM fields generally. In 1987, only 20 per cent of the people working in STEM fields were female, a number that has inched up to just 22 per cent today. As a former research scientist and university professor, you used to be part of that statistic. How has your own experience informed your approach to this file. Specifically, what double-standards do women in STEM face that those outside don’t see?

Have I been the only woman in the room? Yes. Have I been paid in the bottom tenth percentile because I was a woman? Yes. Have I been asked in a department meeting when I planned to get pregnant? Yes. I’ve always worked hard in the job. It shouldn’t be about me. When I go across the country, I am awed, humbled and inspired every day by the tremendous research done every day by women. I hear from them; it still remains difficult. They ask: “Should I have a family or should I have a research career?” No one should have to make that decision. This week I made a comment about a woman who wore her lab coat to hide her pregnancy. This is not okay.

You’ve noted Canada lags behind other nations when it comes to women in science, only 36 per cent of PhDs in science in Canada are earned by women, compared with 49 per cent in the U.K. and 46 per cent in the United States. Why do you think that is—and what can be done about it?

You have to hit it on a number of levels. You have to attract young women and girls. Science opens up a wonderful world. I just had two incredible young women leave my office from McMaster; they’ve started this wonderful science program. I want to get young girls excited in science, tech, engineering mathematics, art, design—and how they come together. We’ve got this Choose Science campaign. Once women are there, though, we have to retain them. When I look at universities, it’s not enough to have role models, we need to have champions. We need to have more women in senior leadership positions. There are issues about work-life balance. Women go to have children and then who keeps the lab running? There are many challenges.

We’re in a big cultural moment in terms of women and STEM. The movie Hidden Figures was surprise blockbuster, and #GirlsInICT is trending on social media. To what extent can government stoke that conversation—and what are you doing to do so?

The Prime Minister did open up the conversation with a gender-balanced cabinet. I try to get out to as many schools as possible. I do as much as I can with young people, with young women. Yesterday, in Montreal, I met two children under the age of 10 who’d created a robot that looked for the sun to get optimal solar radiation. In Cape Breton, I talked to a young woman who wanted to be a coast guard engineer. She said, “You’re the first person who told me that’s possible. Everyone has told me women don’t go into that field.” We’ve got to change that.