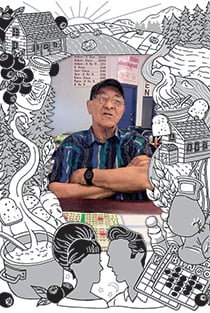

James Hilliard Favel

He left home at 15 to work on farms and in bush camps. In old age, he longed to return to the place he was born.

Illustration by Julia Minamata

Share

James Hilliard Favel was born on Oct. 16, 1935, in a one-room log cabin on the edge of the James Smith Indian reserve in Fort à la Corne, Sask. His father, Miles, was a trapper and farm labourer with French and Native heritage. His mother, Ellen, was Cree.

Jim was the second of 12 children. “We were very poor,” says one of his younger brothers, Wilfred. “It was back in the Depression. We didn’t have much of anything.” The children would pick blueberries in the summer and preserve them to help make it through the winter, and would travel to wherever Miles could find work.

It wasn’t until Jim was 11 that he started school. The family moved to a bigger log cabin—12 by 20 feet—near the local one-room schoolhouse. Jim played softball and hockey with friends on the reserve, and he and his older brother sparred over the attention of girls. But he also had a solitary streak, wandering through the forest to the North Saskatchewan river and sometimes letting Wilfred tag along.

When Jim was 15, he left home and worked on farms, like his father. Before turning 18, he lied about his age and joined the army, enlisting in Prince Albert with the Queen’s Own Rifles. One day, he got a call that his mother had died of a heart attack. She was buried before he made it home. He took it “very, very hard,” Wilfred says, but “kept it all inside of him.” Jim rarely talked about his three years in the army, but he did learn to box. “He was pretty good with his dukes, I’ll tell ya,” says Wilfred.

Jim and his brothers spent winters working in bush camps, cutting telephone polls and sleeping six to a tent. In the late 1950s, he and Wilfred worked for the Thomas Shows’ carnival. “We were ride boys, putting the rides up, taking them down,” Wilfred says. “It didn’t make a heck of a lot of money,” but they got to travel: through the small towns of Saskatchewan, then to bigger cities in Alberta, Ontario and the U.S. Later, Jim spent summers fighting forest fires and working on sugar-beet and potato farms. Over time, he lost touch with many of his siblings.

During the harvest of 1966, on a night out in Taber, Alta., Jim met Agnes Moosewaypayo, another farm worker. Three years his junior, “she was the most beautiful woman you could ever see,” he would later say. It was the era of beehive hairdos and men who looked like Elvis, and that was Agnes and Jim—a handsome couple in love. They did not part after that first night. A few weeks later, Jim found Agnes crying; she missed her six children from a previous relationship. Jim got a $500 advance from his boss at the time and sent her home to the Kinistin Reserve, where Agnes’s mother was caring for the kids. Jim rented a big house in Taber and they all moved in. Jim ended his single, wayward days.

He had three more children with Agnes: Twins Lucy and Maxine were born in 1968, and Tracy was born in 1969. The family moved to the small town of McKague, where they bought a five-acre plot of land. They were hard years and, during that time, Agnes was in a car accident that required hip surgery and forced her onto crutches. Eventually, the family settled in Saskatoon and Jim got a job at a scrap-metal recycling company. Lucy never remembers her father taking a day off.

As Jim’s kids grew, they had kids of their own, and Jim loved them all. Whenever a new baby came along, he would turn up to steal it, his granddaughter, Stacey, jokes. He and Agnes helped raise many of their grandchildren—at one time, 10 filled the house. Gentle and kind-hearted, Jim only yelled to wake the kids up for school. A great pot of porridge and 30 pieces of toast would be waiting in the kitchen.

Soon after Jim retired in 2006, Agnes broke her bad hip, confining her to a wheelchair. Jim pushed her to daily bingo games, and when she went into hospital in the fall of 2012, he visited every day. On Jan. 9, 2013, Agnes died. Jim was devastated. He began sleeping through the days and playing bingo in the evenings.

Jim started talking about visiting Fort à la Corne again. He planned a trip with brother Wilfred, who flew in from Arizona and, on Aug.14, they drove past where the old schoolhouse used to be. “He had a smile on his face,” Wilfred says. “He said, ‘I don’t know how I’m going to pay you for all this.’ ”

Five days later, Jim was walking home from bingo when he was suddenly attacked and beaten. He died of his injuries. Police are investigating his death as a homicide. He leaves behind 28 grandchildren, 44 great-grandchildren and two great-great-grandchildren. He was 78.