Walking in the footsteps of the victims of Flight 752

The Tehran air crash victims followed a path of hope to Canada. We learn much by walking in their footsteps.

Several hundred people gather around the Centennial flame in Ottawa for a vigil to remember those killed on Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752. (Adrian Wyld/CP)

Share

One of the routes to the heartbreak of North Vancouver’s Lonsdale Avenue is a winding path through a linear park that follows Keith Road. You’ll pass the city’s cenotaph there, as well as a towering grey air-raid siren, decommissioned in a bout of short-lived optimism. The siren bears a plaque celebrating the end of the Cold War, and “of the tension that once existed between the West and the former Soviet Union.”

The quiet park is a far remove from the mangled remains of 176 victims of Ukrainian International Airlines Flight 752, blasted from the Tehran sky by Islamic Revolutionary Guards. Yet its two shrines stood with the flickering memorial candles of Lonsdale through the grey days of January as reminders that ideals of peace, security and justice are fragile things.

They are—we are—vulnerable to the ill winds of distant conflicts. They can be snuffed in the 20 seconds it took to fire two anti-aircraft missiles at a civilian airliner. Where does the blame begin for what Alberta Premier Jason Kenney called an “epic demonstration of human folly”?

Obviously, the irrefutable facts of this debacle forced the hardline Iranian regime to admit responsibility, whatever that may eventually mean. But those who initiated the launch were merely the lowliest links of a daisy chain of greed, venality and miscalculation reaching back decades, and across borders.

FLIGHT 752: A family torn apart

From the park we reach Lonsdale Avenue, which climbs in a steep, straight shot from Burrard Inlet toward the North Shore Mountains. To walk it is to appreciate what the Persian community built here over the four decades since Iran’s revolution installed an unbending Islamic regime. And to mourn what was lost in the blink of an eye.

Vancouver’s North Shore is home to one of Canada’s larger concentrations of Iranian immigrants, but they have settled in every corner of Canada, determined to regain the voice and freedom stripped from them in their homeland.

For many here, Lonsdale is their main street, but there are many such communities across Canada. It’s a place to shop for fruit and nuts, meat and vegetables, breads and honey-drenched desserts. It is a place to dine in a growing number of Persian restaurants, to book travel, or to gather at Arash Azrahimi’s Rosewood Studios for family portraits. “It is important,” his website says, “to have a memory of your family captured for eternity.”

For too many, photos and memories are all that remain.

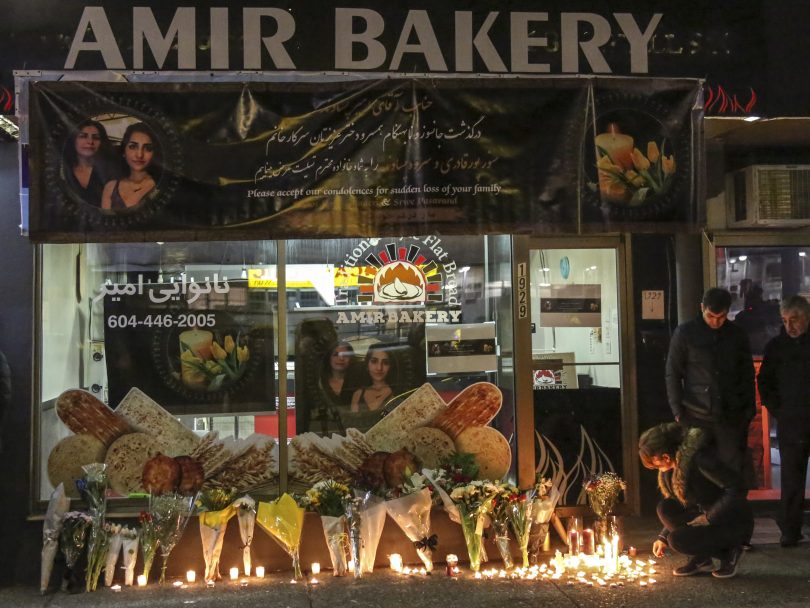

A few blocks north is a heartbreaking memorial in front of Amir Bakery, the family business of Amir Pasavand, his wife, Ayeshe Pourghaderi, and their high school-aged daughter Fatemeh.

Amir is left to mourn his wife and daughter after their vacation ended in tragedy. The front sidewalk is jammed with candles, wilting bouquets and messages of condolence. A banner bearing a beautiful portrait of the women stretches the length of the storefront.

The street is shared, of course, with Anglo shopkeepers, Vietnamese nail salons, Indian restaurants and condo towers holding a veritable UN of ethnicities.

It is my main street, too. But witnessing the national outpouring of grief, I’ve come to see Lonsdale as representing something larger, a path stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific to the Arctic oceans.

In North Vancouver, the toll also includes two doctors, Firouzeh Madani and Naser Pourshabanoshibi, a wife and husband who were determined to qualify as Canadian physicians. There was Langara College student Delaram Dadashnejad, an accidental passenger on the flight due to a delay in her travel documents. And engineer Mohammad Hossein “Daniel” Saket and his new wife, Fatemeh “Faye” Kazerani, a biomedical medical engineering grad working as a cardiology assistant.

All gone.

Each life is at once unique and representative of the sacrifices and accomplishments of the whole. Some 50 universities and colleges alone were impacted by the deaths of the 138 Canada-bound passengers on Flight 752.

The dead were teachers, students, professionals, employees and employers. They were children. Kurdia Molani of Ajax, Ont., “a beautiful bundle of joy,” said her obituary, was one year old. Jiwan Rahimi of Stouffville, Ont., was three. His mother, Farideh Gholami, was seven months pregnant.

All gone.

Numerous studies attempt to calculate the so-called opportunity costs of war. One puts the cumulative price of the ceaseless Middle Eastern conflicts at US$12 trillion. But that tells us nothing.

What are the opportunity costs of Jiwan, a bright three-year-old, or little Kurdia? Might they have been musicians or scholars or great leaders?

What is the opportunity cost of Mansour Pourjam, an Ottawa dental technician, a Carleton University alumnus and proud single dad? Pray he died knowing his lessons of positivity and strength live in his son Ryan. This slight, solemn boy, with wire-rimmed glasses and a shock of Dennis the Menace hair, eulogized his father at a Carleton University memorial service with composure and eloquence far beyond his 13 years.

“I stand up here a week after this horrible tragedy, and I still can’t believe it,” Ryan said. “I feel like I’m dreaming. But I know that if I was dreaming, and that if he woke me up, he’d tell me that it’s going to be okay. And it will be.”

A video of Ryan’s eulogy has spread across the internet. It is three minutes of grace and strength that will bring you to your knees.

Many in the Iranian community take comfort from the leadership Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has shown since the tragedy. And in his inspiring and perhaps naïve vow that “We will not rest until there is justice and accountability.”

‘They wanted a simple life’: Remembering Razgar Rahimi, Farideh Gholami and Jiwan Rahimi

‘Her heart was like the ocean’: Remembering Niloufar Sadr

‘They were both go-getters’: Remembering Arvin Morattab and Aida Farzaneh

Just days after Iran’s admission of responsibility, the country’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, lashed out in a rare and fiery sermon calling the downing of the jet “an excuse to undermine” the Revolutionary Guard, and condemning the legions of protesters in his country as “stooges of the United States.”

Still, Trudeau’s commitment confirms the faith that 32-year-old Navid Lambert-Shirzadi showed in Canada when he left Iran 10 years ago for a better life. He’s used that decade productively, earning a master’s and a Ph.D. at the University of British Columbia, taking a job as a machine-learning engineer, and starting a family with his wife, Erika, and four-month-old daughter Sequoia.

Trust is a precious word to Navid. “I trust the Canadian government to be on top of this. To follow up. To make sure we understand what happened,” he says. “I trust the Canadian government to make sure that damages are paid, people are compensated. And I trust the Canadian government to support the community. It’s a big loss to recover from.”

He speaks in a quiet corner of a packed memorial for his friends and North Vancouver neighbours Daniel Saket and Faye Kazerani. He looks at the hundreds gathered for the memorial, a mix of religions, races and ethnicities. They’re jammed into the recreational complex of North Vancouver’s Seylynn Village, a community of three condo towers that Daniel Saket, a mechanical engineer, played a key role in designing and building, and where he and Faye lived.

Here, sorrow and loss pushed away anger, at least for these few hours. There’s little talk of ethnicity, Navid says. “Everyone talks of the people on the plane as Canadians.” His voice wobbles. “To me, that’s why Canada is our home.”

Across the room, Sydnie Nicoll looks at a giant screen cycling through photos of Daniel and Faye’s adventures in Canada. “I think you see the goodness in them, it’s true. It’s authentic.” She calls herself “just a Canadian,” though she married into the Iranian family that developed this condominium project. Faye became both a relative through marriage and a friend. “She took me under her wing because I don’t know the culture much myself. She was just so generous in explaining things to me.”

Nicoll visited Iran last year, but while the experience was amazing, she’s hesitant about a return. “My own experience as a Canadian is being so sheltered from tragedy and war. It worries me, but I don’t know if that’s valid. I think it is.”

That afternoon, across Burrard Inlet, members of an Iranian solidarity movement rally on the plaza in front of the Vancouver Art Gallery. Here the tone is markedly different. A wild wind scours the open space, tearing at placards, flattening folding chairs, ripping words from the mouths of the impassioned speakers.

“On this windy day we are all sad, we are all angry,” says Mehran Azami, who came to Canada 27 years ago. “Those who died wanted a better life, to live in a free country. Wanted kindness, wanted to live, to grow, to help others. Canada cries for humanity.”

Off stage, she says she was arrested at 19 for protesting against the regime. She was tortured during two years in jail. A brother was killed and now a young niece is imprisoned.

Yet, she hopes the attempt to hide its culpability may topple the Islamic regime. “The discontent is more powerful than it’s ever been. It’s going to change.”

A man who also left Iran after the revolution echoed that view at the North Vancouver memorial. He flipped through his phone, sharing video of protesters earlier that day at Sharif University of Technology in Tehran. “This gives me hope.”

In the days before the downing of the jet, he was among dozens of people of Iranian origin detained and interrogated at the Peace Arch crossing into Blaine, Wash. Although he is an American citizen living in Canada, Homeland Security agents held him for nine hours in the confusion and amped-up security after the U.S. assassination of Iran’s top military leader.

As he recounted being trapped between two belligerent countries, his face clouded and he asked that his name not be used. “See, this is what they’ve done to all of us,” he said, embarrassed. “I don’t know whether to be afraid of Trump and his government, or Iran and their government.”

He leaned in, summoning a wan smile. “If you happen to know Mr. Trudeau, I’ll happily trade our American passports for Canadian.”

I take a familiar walk along my main street, reflecting on the faith that so many place in the Canadian’s pledge of justice and accountability. I hope they’re right.

Conflicted notions of the elusive ideal of justice compel a final stop at the Lonsdale headquarters of Family Services of the North Shore, an organization that has stepped up to offer emotional support for those grieving the Tehran crash.

It’s another mass murder that draws me inside. Some 35 years ago, another plane was blown out of the sky, this one by a suitcase bomb planted by Sikh extremists at Vancouver International Airport. All 329 people aboard Air India Flight 182 were killed, including 84 children under the age of 12.

There were also promises of justice back then. And attempts were made. A $100-million RCMP investigation resulted, finally in 2000, in the arrest of two men.

I’m here to see Perviz Madon, whose husband, Sam, was murdered in that disaster. She was left at 36 to raise two young children, Eddie and Natasha, and to grieve in public.

We spoke often during the interminable grind of the RCMP investigation, the subsequent arrests and trial, and its shocking outcome. In March 2005, almost 20 years after the bombing, and the end of 350 trial days, we were in Vancouver’s bomb-proof courtroom to hear the verdict.

The prosecution fell “markedly short” of proof beyond a reasonable doubt, the judge ruled. The accused were acquitted and set free.

Natasha, just five when her father was killed, fell sobbing into her mother’s arms; a sight impossible to forget. No one has ever been convicted of murder in the case.

I want to ask Perviz, now an intake counsellor at Family Services, about this elusive thing called justice.

She emerges with a smile. “Empathy” is written in bold letters on the office door. She is polite but firm: after 35 years, she is determined not to relive the past, at least not in public. Perhaps, too, she feels the focus must stay on those grieving this latest tragedy.

Yes, she concedes, this dredges up memories. “How can it not?” We leave it at that, though with tacit agreement that the national response is different today, more compassionate.

In the immediate aftermath of the crash in 1985, then-prime minister Brian Mulroney called India’s prime minister to offer Canada’s condolences, slow to appreciate that the huge majority of the dead were Canadians. We’ve been playing catch-up ever since.

If we’ve learned anything in the years that followed, it’s in a telling shift of attitude. There were 138 people bound for Canada who never arrived. And in memorial services from Atlantic Canada to Yellowknife, they were mourned as family. No them. This time, they are us.

Maybe together, as young Ryan said, “It’s going to be okay.”

That’s not justice. Not yet. But perhaps it’s a start down that street.

Ken MacQueen is an award-winning writer and a former Vancouver bureau chief of Maclean’s

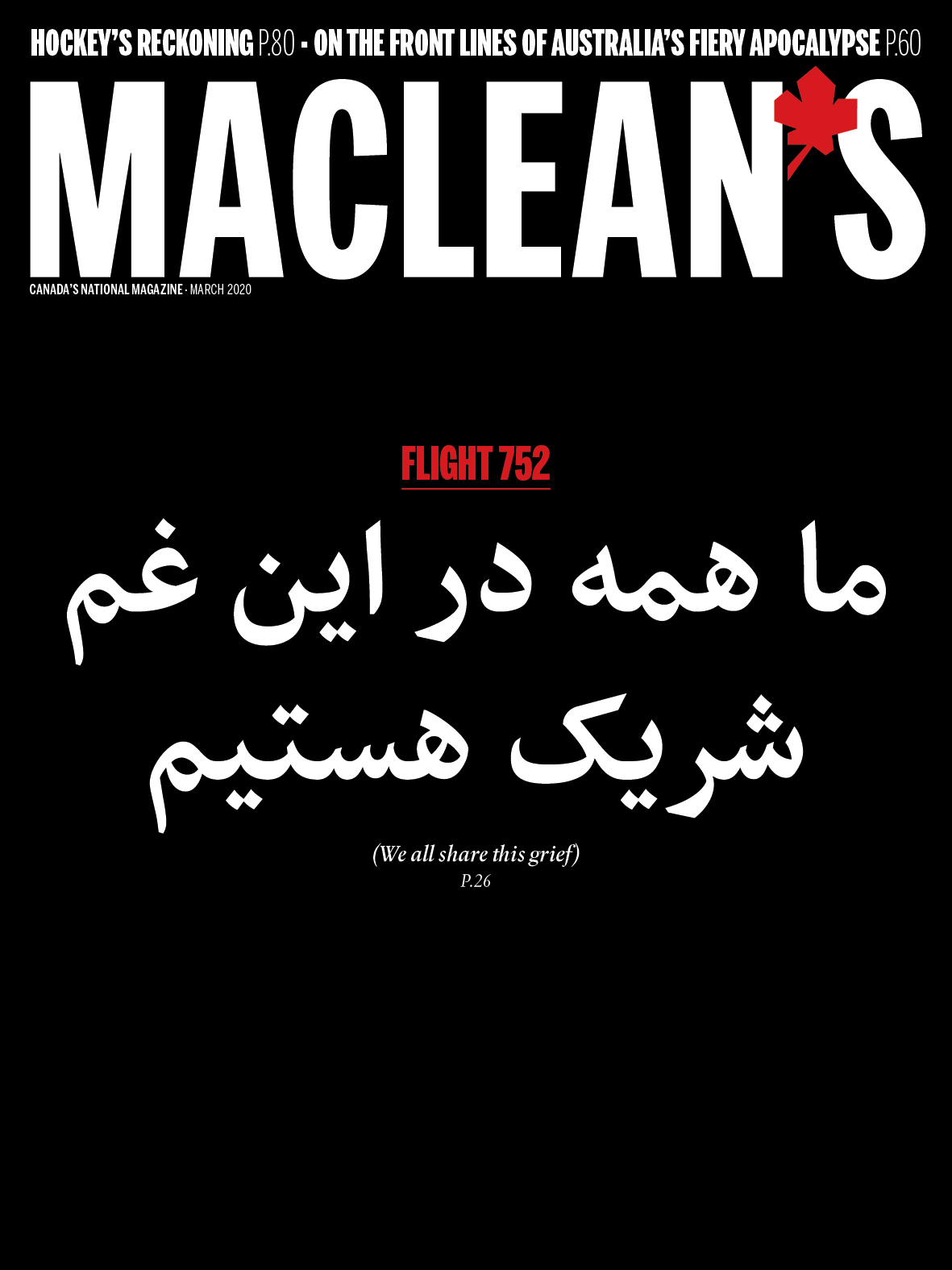

This essay appears in print in the March 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “’Canada cries for humanity.’” On our cover this month, we offer a Farsi expression of condolence to illustrate a collective spirit of national devastation after the downing of Flight 752. Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.